Sleep

The Real Reason Why Mondays Are So Miserable

... and the one shift that can make them better.

Posted August 14, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Mondays are linked to increases in stress, suicides, and even heart attacks.

- The stress and health risks observed on Mondays are mostly explained by weekend changes in our sleep cycles.

- Disrupted sleep cycles cause hormone changes that result in fatigue, stress, and impaired organ function.

- Sticking to the same schedule on the weekend as you do during the week can make Mondays more pleasant and less stressful.

There is no other day like Monday in the U.S. While we "thank God" for Friday, celebrate the weekend, and at least tolerate Tuesday through Thursday, Monday to most people is the emotional equivalent of the rock in Charlie Brown's Halloween candy. Against otherwise near-universal antipathy, perhaps Monday's only saving grace is being the most common day for federal holidays.

Unpopularity is only the beginning of Monday's problems, however. Monday, for example, is associated with the highest levels of emotional stress, the lowest rates of work productivity, and higher rates of suicides for both men and women (1). And these adverse psychological and behavioral outcomes are paralleled with remarkable precision by increases in negative physical health outcomes such as workplace accidents and even strokes and heart attacks (2).

Arguably the most infamous and dangerous Monday of all is the "spring forward" Monday following the March daylight savings time weekend. Studies indicate that a 6 to 8 percent increase in fatal car accidents—translating to two to three dozen excess deaths each year—occur on this grim Monday (3).

Why Are Mondays So Hard?

Why is Monday such a recurring wrecking ball on our physical and emotional health and what can we do to prevent it? In the case of the daylight savings effect, there is a near-annual exercise by Congress to solve this problem by canceling daylight savings entirely (e.g., 4). However, because of the varied and arguably negative effects of such legislation in areas such as the northeastern U.S. (where the absence of daylight savings would increase daytime darkness), this effort rarely gains traction. And even if the daylight savings ritual did become a memory, we would still bear the other negative Monday consequences. For this reason, a broader and more practical solution is clearly necessary.

To understand the solution, it is first necessary to explain the surprising power of sleep deprivation and circadian dysfunction. Subjectively, most people underestimate the effects of changing their sleep patterns on their health and function. Although laboratory studies, for example, indicate that even one to two hours of reduced sleep produces measurable cognitive impairment, hormone disruption, accelerated biological aging, and even adverse patterns of gene activation, most of these changes are invisible to our conscious awareness. Only when the effects reach a threshold of high intensity—such as jet lag or episodes of insomnia—do we typically notice them.

In the case of jet lag, most adults are familiar with the combination of fatigue, mental slowing, and increased negative affect that results from traveling across multiple time zones, as well as the days of recovery often needed to restore normal feelings and function. Jet lag is an example of the circadian disruption that occurs when our sleep-wake cycle becomes misaligned with the 24-hour schedule to which our body is accustomed. And the cognitive, emotional, and physical side effects of jet lag are caused by a complex collection of hormones whose careful regulation has gone awry.

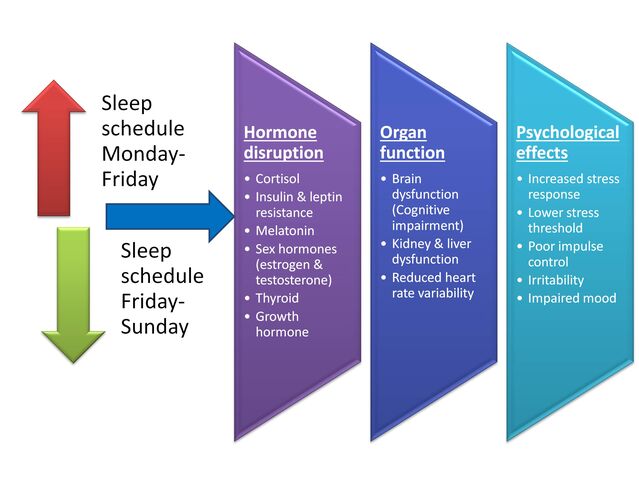

Although jet lag and the painful symptoms of circadian dysfunction that result from multiple time zone changes are rare events for most Americans, tens of millions unintentionally induce an only slightly less severe case of "social jet lag" or "weekend jet lag" on themselves every week. As shown in the table below, the typical person in the U.S. follows a markedly different sleep schedule from Monday to Friday than from Friday to Sunday. In many cases, this change in the sleep-wake cycle is as much as several hours.

Following a week of regular school or work hours, for example, a person may take advantage of their obligation-free Saturday to both stay up later on Friday night and sleep in on Saturday morning. A similar pattern may be followed on Saturday night and Sunday morning.

In this mere 48 hours, the sleep-wake alteration markedly shifts the person's internal clock and hormone cycles. For example, cortisol (our primary stress hormone) levels that typically rise one to two hours before the person rises for school or work (early a.m. cortisol helps us wake up in the morning but typically declines after this cyclic peak) shift to occur a couple of hours later due to their later waking time. Similarly, melatonin levels—normally peaking in the evening hours before the person is retiring before their school/workday—now start later across the weekend to align with their later bedtime.

And many other hormones partly regulated by circadian mechanisms such as estrogen, testosterone, growth hormone, thyroid hormone, insulin, and other appetite hormones all scramble to catch up. These hormone cycles have profound effects not only on our feelings of well-being but even on the function of our internal organs. Therefore, when we're out of alignment with our natural sleep schedules, we become vulnerable to a host of negative physical and psychological consequences.

Then comes Monday. Following 48 hours of a late-shifted sleep-wake cycle, our cortisol levels are now peaking during our commute to work and across the morning instead of before waking up. Increased stress and negative affect are the subjective results.

The delayed melatonin release in the evenings caused by the weekend means it will be harder to fall asleep Monday night. Waking up much earlier on Monday than on Saturday and Sunday has probably also induced insulin and leptin resistance, affecting mood, cognitive function, appetite, and blood glucose control (sure enough, blood glucose tends to be worse on Mondays; (5)). The effects of this hormone dysregulation are so strong as to even reduce the ability of our hearts to respond to stress, increasing our risk of cardiovascular events such as heart attacks.

What Can Be Done to Make Mondays Better?

The most effective and practical solution to our culture of Monday maladies is to minimize changes in our sleep-wake cycle between weekdays and weekends. If the physical and psychological harms associated with Mondays are the result of hormone disruptions caused by weekend changes in our circadian cycle, the natural remedy is to reduce the degree of these circadian changes.

This solution is firmly grounded in science. For example, studies show that the degree of impairment in heart rate variability caused by social/weekend jetlag is directly related to the size of the difference in sleep-wake cycles during the week versus the weekend and, critically, is absent among those who follow the same sleep-wake cycle across all days of the week (6). Put simply, people who practice a consistent sleep-wake pattern across the week feel and function as well on Mondays as on other days of the week.

Is it worth getting off the sleep-wake cycle roller coaster to enjoy consistently better physical and emotional health? Unfortunately, this isn't a question science can answer for you. The demands of work and school, coupled with weekend temptations, make this a difficult choice for many Americans.

At least, however, sleep and circadian research do clarify for us that Monday misery is a choice.

Facebook image: Prostock-studio/Shutterstock

LinkedIn image: Kateryna Onyshchuk/Shutterstock

References

1. Maldonado G, Kraus JF. Variation in suicide occurrence by time of day, day of the week, month, and lunar phase. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1991 Summer;21(2):174-87. PMID: 1887454.

3. Josef Fritz, Trang VoPham, Kenneth P. Wright, Céline Vetter. A Chronobiological Evaluation of the Acute Effects of Daylight Saving Time on Traffic Accident Risk. Current Biology, 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.045

5. Clemmensen KKB, Quist JS, Vistisen D, Witte DR, Jonsson A, Pedersen O, Hansen T, Holst JJ, Lauritzen T, Jørgensen ME, Torekov S, Færch K. Role of fasting duration and weekday in incretin and glucose regulation. Endocr Connect. 2020 Apr;9(4):279-288. doi: 10.1530/EC-20-0009. PMID: 32163918; PMCID: PMC7159259.

6. Sűdy ÁR, Ella K, Bódizs R, Káldi K. Association of Social Jetlag With Sleep Quality and Autonomic Cardiac Control During Sleep in Young Healthy Men. Front Neurosci. 2019 Sep 6;13:950. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00950. PMID: 31555086; PMCID: PMC6742749.