Trauma

Creating Transitional Spaces for Intergenerational Trauma

Trauma creates disconnection and conflict. How do we create belonging?

Updated October 16, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Presence and community can help create the necessary transitional spaces for intergenerational trauma.

- Cruelty has created a chasm of open, festering wounds that cannot be denied and must be faced.

- If we can be here for each other, we can start to shift the narrative of cruelty that has harmed many people.

This is Part 3 of a four-part series on trauma and healing. Links to other parts in references.

In October 2022, I was invited to be on a panel for Tadaima, the online Japanese American pilgrimage. (Tadaima means “I’m home” in Japanese.) Our discussion, titled “Speaking Out and Calling In with Bravery and Humility: A Conversation with Dr. Ravi Chandra,” was moderated by organizer Julie Abo, and included her mother, Mary Abo, who was incarcerated at Minidoka as a child, and Mike Ishii and Rikio Inouye, both activists and scholars in the Japanese American community. I was invited to be on the panel because of my long history with the Japanese American community, and because of two articles I’d recently written. The first, a post on Psychology Today, was about humility, and was recently republished by The Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley. The second, at East Wind eZine, questioned the “good heartedness” of Trump supporters and their opponents. Our YouTube conversation is linked below, and all these pieces are in the references. (The conversation is available as an audio podcast on SoundCloud and Apple Podcasts and on YouTube.)

I stated that my ideal was having a “cool head and a warm heart” when dealing with disagreements and conflict, but this is quite difficult when one is facing perceived and actual personal threats, threats to loved ones, or the broad cultural threats of racism and violence. It’s often “one thing after another” for traumatized and vulnerable people, and the apple cart of the mind/heart is frequently tipped over. Sometimes it’s absolutely necessary to express anger, or to “blow the conch shell” as the Dalai Lama wrote in Healing Anger: The Power of Patience from a Buddhist Perspective. Anger reveals wounds within and between us that must be healed, yet still fester.

I opened my remarks with an example of my own anger when faced with racist comments on the streets of San Francisco last year. Racism is the great unhealed wound of American life, a major factor in recent violence in September 2023, such as the incident at Seattle’s Wing Luke museum, and a white man’s beating of a 6-year-old boy with a baseball bat in Texas. Racism naturally provokes anger and the compassionate wish to help set the world on a better path.

It can take a village to set the apple cart of the mind right again, and to deepen a sense of self grounded in love, and not simply antagonism or the response to antagonism (see Part 2 of this series, "Cultivating Sense of Self to Cope With Trauma and Life"). I’m grateful to be in solidarity and community with Japanese Americans and all who have suffered injustice and who have compassion for others who suffer. I hope the conversation, now on YouTube, will be a soothing reminder that presence and relatedness can restore what has been damaged by the great chasm in empathy caused by the pursuit of domination and self- or faction-centered power. (You might also like my post on Psychology Today and podcast “The Dim Sum Dialogues,” centered on creating communities to share both positive emotions and distress. This is also in the references below.)

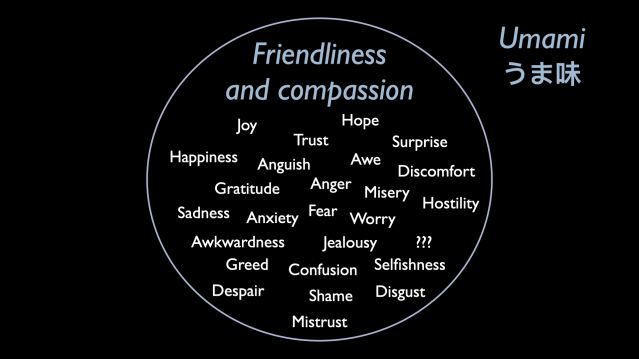

Presence, understanding, friendliness, calm, compassion, love, and community help create the necessary transitional spaces for intergenerational trauma. I call friendliness and compassion the umami of the mind/heart: they make our inner lives and relatedness more tasty and delicious.

Cruelty and callousness often attack human vulnerability. But if we can be here for each other, we might be able to shift the narrative of cruelty that has harmed and continues to harm American personal, political, and social life.

Even now, many Americans do not know about the U.S. government’s racist, unconstitutional, and immoral treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II that has been called “one of the greatest violations of civil rights in U.S. history” (Irons, 1983, quoted in Nagata et al, 2015). But rising from these wounds, the Japanese American community has cultivated a great body of wisdom on healing intergenerational trauma, which can help all Americans cultivate a transitional space to heal from the long scars of American history and dream of a future to believe in.

120,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were young, U.S.-born citizens, were forcibly removed from the West Coast in 1942 by President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. They were moved through 15 assembly centers into 10 confinement sites, also known as incarceration, concentration, or imprisonment camps. 46 years later, President Reagan signed the Civil Rights Act of 1988, which finally apologized to Japanese Americans for the unjust removal and incarceration, and provided $20,000 to each living survivor. This was the result of activism and protest that started in the Japanese American community during the forced evacuation and which gained momentum in the 1960s and '70s leading to the founding of the redress and reparations movement and President Carter’s formation of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). The CWRIC concluded that the internment was not a military necessity but instead resulted from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” (CWRIC, 1997, p. 18, quoted in Nagata et al, 2015).

The $20,000 paid out to each of about 82,000 survivors could only be considered a down payment of the estimated $3.64 billion estimated wealth lost (in 2022 dollars). And no amount of money can compensate for the individual, relational, and cultural trauma that has left a long tail and is still ongoing. “Individual trauma shatters one’s assumptive world, sense of self, and well-being” (Caruth, 1995, quoted in Nagata et al, 2015). Cultural trauma “occurs when members of a collectivity feel they have been subjected to a traumatic event that leaves indelible marks upon their group consciousness, marking memories forever and changing their future identity” (Alexander, 2004, quoted in Nagata et al, 2015). Individual, race-based, cultural, historical, and intergenerational trauma can lead to significant and even overwhelming mental, emotional, relational, and physical health sequelae.

From the Smithsonian Magazine article in references:

“Families “were stripped of their identity,” says Noriko Sanefuji, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The incarcerees’ names were no longer important. Instead, each family received a five-digit number to be worn on a tag around their necks. “That becomes who you are,” she says. “Even the offspring who never experienced the camp—the third generation, the fourth generation—it’s an ongoing trauma.” This loss of identity, she believes, is almost like a part of their DNA, passed from generation to generation.”

From my own East Wind eZine essay on racism published in 2020 (in references):

“To quote Sox Kitashima’s famous speech on August 12, 1989 before the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations, which was further immortalized by Jon Jang and the Pan Asian Arkestra on their album Never Give Up: Let Us Not Forget (available online):

“Let us not forget the trauma experienced with evacuation: the loss of property, both real and personal; the loss of earnings; the loss of human and civil rights during World War II. The wives and young children left with evacuation decisions because their husbands and fathers were taken away earlier. The deep furrows on the faces of our elderly; the loss of a lifetime of work; the agony of being helpless. I shall never forget the testimony of a mother with two small children shocked by the action of two military police. While waiting for her husband to return home, they knocked every picture off the wall, threw her Buddhist shrine outside and smashed it to pieces, tore up all the mattresses. The children were too scared to sleep by themselves. Military necessity, a weak excuse for racism, was never justified…”

In 2021, Congresswoman Doris Matsui recalled the concentration camps before a congressional subcommittee addressing 21st-century attacks on Asian Americans. “We have seen the consequences when we go down that path,” she said. “My family has lived through these consequences. This is what we are working to root out from the deepest place in our social conscience” (from Smithsonian Magazine article in references).

Cruelty lives in the deepest places of our human and American psyche. It has created a great chasm of open, festering, communicating wounds that cannot be denied and must be faced. We are doing that in real time, as any glance at the headlines tells us.

“We have seen the consequences when we go down that path” of cruelty. I hope and pray we do better.

References

The conversation referenced in the article can be found on YouTube here Speaking Out and Calling In with Bravery and Humility: A Conversation with Dr. Ravi Chandra October 15, 2022

Wing Luke Museum incident: Mayer M. Balang R. Wing Luke Museum hate crime — Suspect: “The Chinese ruined my life” Northwest Asian Weekly, September 15, 2023

GoFundme for 6-year old beaten by a white man in Georgetown, Texas, and KVUE story about the incident on YouTube

Four-part series on Trauma and Healing:

Part 1: Dr. Satsuki Ina on Japanese American Trauma and Healing (September 26, 2023)

Part 2: Cultivating Sense of Self to Cope With Trauma and Life (October 3, 2023)

Part 3: Creating Transitional Spaces for Intergenerational Trauma (this post, October 5, 2023)

Part 4: Abusive Power and Megalomania Perpetuate Trauma (October 15, 2023)

Chandra R. Eight Types of Humility Needed for Cognitive Clarity | Psychology Today. Pacific Heart Blog, Psychology Today, September 8, 2022

Chandra R. The Eight Kinds of Humility That Can Help You Stay Grounded. Greater Good Science Center, August 22, 2023

Chandra R. MOSF 17.11: Do Trump Supporters or Their Opponents Have “Good Hearts”? East Wind eZine, October 6, 2022

Chandra R. What Do We Feel When We Feel Close? The Dim Sum Dialogues. Pacific Heart Blog on Psychology Today, September 19, 2023

Chandra R. Memoirs of a Superfan Volume 15.3: Rejecting Donald Trump’s Racist Visions! September 7, 2020, East Wind eZine

Nagata DK, Kim JHJ, Nguyen TU. Processing Cultural Trauma: Intergenerational Effects of the Japanese American Incarceration. J Soc Issues, June 11, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12115

Nagata DK, Kim JHJ, Wu K. The Japanese American wartime incarceration: Examining the scope of racial trauma. Am Psychol. 2019 Jan;74(1):36-48. doi: 10.1037/amp0000303. PMID: 30652898; PMCID: PMC6354763.

Rep. Doris Matsui calls anti-Asian hate a “systemic problem” PBS NewsHour. Testimony before House Judiciary Committee, March 18, 2021

Meyer M, Bayang R. Wing Luke Museum hate crime — Suspect: “The Chinese ruined my life”. Northwest Asian Weekly, September 15, 2023

KVUE. Georgetown father opens up after brutal attack on 6-year-old son. KVUE News on YouTube, September 14, 2023

Chandra R. Extremism: Leaders push an ecosystem for violence. YouTube playlist. Curated starting August 27, 2023

George A. Eighty Years After the U.S. Incarcerated 120,000 Japanese Americans, Trauma and Scars Still Remain.Smithsonian Magazine, February 11, 2022

Chandra R. Asian American Anger: It’s a Thing! The #DVChallenge. Pacific Heart Books, 2014. Available for free download at https://ravichandramd.com/portfolio/asianamericananger/