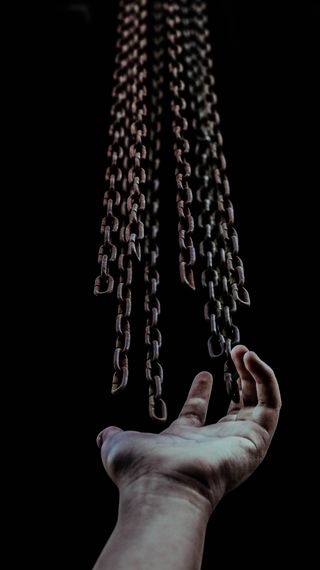

Trauma

What Will It Be Like When the Lockdown Lifts?

Mental health aftershocks will linger and recovery will take time.

Posted April 15, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Although we don’t know exactly when, at some point in the future self-isolation will end, and many of us will return to offices, restaurants, and houses of worship. But what will that look like?

One thing for sure, we will never return to normal; we will return to “a new normal.” And each of us will have repair work to do as we re-enter the world of physical proximity to coworkers and reconnecting with friends, neighbors, and loved ones. And not just contagion worries. Many of us will face recovery from the psychological trauma of having lived under chronic uncertainty, isolation, financial insecurity, job loss, and for some, the death of friends and loved ones—taken together, enough trauma for a massive mental health crisis.

The trauma, like the virus, will not simply disappear. For some, it will continue to linger in our memories, daydreams, and nightmares. What can we expect and what measures can we take?

Disaster researchers warn that the pandemic could inflict long-lasting psychological trauma on an unprecedented global scale. With some 2.6 billion people worldwide in some kind of lockdown, Elke Van Hoof, Professor of health psychology and primary care psychology at Vrije Universiteit Brussel, calls lockdown the biggest psychological experiment and predicts we will pay the price through a secondary epidemic of burnout and stress-related absenteeism in the latter half of 2020. Van Hoof cites one study in China, where parents were quarantined with children, that reported no less than 28 percent of quarantined parents warranted a diagnosis of “trauma-related mental health disorder":

“In short, and perhaps unsurprisingly, people who are quarantined are very likely to develop a wide range of symptoms of psychological stress and disorder, including low mood, insomnia, stress, anxiety, anger, irritability, emotional exhaustion, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Low mood and irritability specifically stand out as being very common, the study notes.”

I spoke with Elaine Miller-Karas, author of Building Resilience to Trauma: The Trauma and Community Resiliency Models and co-founder and Director of Innovation, Vision, and Creativity of the Trauma Resource Institute in Claremont, California. She underscored the unknown in a rolling re-entry: “Until there is a vaccine, which may be up to two years, many of us will not feel safe venturing back into our communities and yet will be required to do so to support ourselves and our families. Essential service workers leave their homes every day now not knowing if today may be the day they become exposed to the virus.”

Miller-Karas told me that one description of trauma is simply too much or too little for too long. She said people worldwide are under a perceived “inescapable attack” from an invisible enemy, which causes an imbalance in the nervous system. The stress response is set off and continually loads our bodies with hormones meant for short action. The kinds of things we might notice are accelerated heart rate, rapid breathing, and fatigue. After a prolonged period of time, our bodies become depleted, impacting our thoughts and sense of well-being, leading to a plethora of mental health conditions including anxiety and depressive disorders.

Human contact is essential for healthy completion of psychological mourning. But with added self-distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, grief—a lonely and isolating experience unto itself—can be compounded and prolonged long after quarantines are lifted. Without appropriate human contact, many people are at risk of prolonged grief disorder (PGD) and complicated grief (CG)—a syndrome affecting 10 to 20 percent of people, characterized by preoccupying and disabling symptoms such as depression, somatic distress, and social withdrawal that can persist for decades.

After re-entry, Miller-Karas cited other lingering aftershocks from the earth-shattering ravages of the pandemic:

- Lingering risk of potential health threat and infection.

- Continued fear of losing loved ones.

- Prolonged and complicated grief from the inability to mourn the death of loved ones.

- Financial and food insecurity.

- Moral injuries from health care workers being asked to reuse protective equipment while knowing it can harm them.

- More homeless families living in their cars due to job loss.

- Tremendous aftereffects with children and spouses under lockdown with alcoholics, drug addicts, and violent family members.

Promising Research on the Horizon

Miller-Karas cited promising research from Emory University using a trauma intervention called the Community Resilience Model (CRM). After a three-hour training, medical personnel participating in trauma resiliency training reported improvements in well-being (80%), resilience (40%), secondary traumatic stress reactions (62.5%), and somatic symptoms (60%). Training with this model is available nationwide. (For more information visit the Trauma Resource Institute.)

Self-Care: Your First Line of Defense

During a disaster like the pandemic, always putting yourself at the end of the line is a grave disservice that actually works against you. Self-care makes your use of time more sustainable. Healthy eating, rest, and regular exercise give you the stamina to withstand any threat to your survival. Take good care of yourself first, and you will have more to give to others.

Remember H-A-L-T. When worry and stress take hold, stop and ask yourself if you are Hungry, Angry, Lonely, or Tired. This alert signal can bring you back into balance. If one or a combination of the four states is present, slow down, take a few breaths, and chill. If you’re hungry, take the time to eat. If you’re angry, address it in a healthy manner. If you’re lonely, reach out to someone you trust. And if you’re tired, rest.

Indulge yourself. You deserve it. When was the last time you soaked in a hot bath or indulged in a restorative activity that rejuvenates your mind and body and restores your energy and peace of mind? Make a 10 or 15-minute appointment with yourself, and schedule personal time for a hobby, a hot bath, yoga, a facial, reading, contemplating nature, or meditation.

Limit news feeds. Restrict your intake of COVID-19 media to just enough to keep up with the latest relevant progress. And make virtual social dates with family and friends a priority.

Additional trauma resources

- SAMHSA’s National Center for Trauma-Informed Care facilitates the adoption of trauma-informed environments in the delivery of a broad range of services including mental health, substance use, housing, vocational or employment support, domestic violence, and victim assistance and peer support.

- The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors’ National Center for Trauma-Informed Care (NCTIC) promotes trauma-informed practices in the delivery of services to violence- and trauma-exposed individuals seeking support for recovery and healing.

- The National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health provides training, support, and consultation to advocates, mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, legal professionals, and policymakers as they work to improve responses to survivors and their children.

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) assists in the improvement of access to care, treatment, and services for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events.

- If you, or someone you care about, is feeling overwhelmed by sadness, depression, or anxiety, or you feel like you want to harm yourself or others, contact the Disaster Distress Helpline (1-800-985-5990).

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Ksenia She/Shutterstock

References

Brooks, SK, et al., (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395 (10227), 912-920.

Grabbe, L. et. al. (2020). Community resiliency model randomized control trial with nurses. Nursing Outlook. (Nursing Outlook. 2019 Dec 30. pii: S0029-6554(19)30325-2.doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2019.11.002)

Matthews, LR, Quinlan, MG, & Bohle, P. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and prolonged grief disorder in families bereaved by a traumatic Workplace death: The need for satisfactory information and support. Dialogues of Clinical Neuroscience, 14 (2): 195-202.

Miller, MD. (2015). Complicated grief in late life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18 (5): 438-446.