Stress

What Does 'Allostatic Load' Mean for Your Health?

Building resilience makes sense because your body pays for a lifetime of stress.

Posted October 26, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

As the popular 2020 Apocalypse Bingo meme jokingly emphasizes, it’s been a stressful year. This makes me worry about our health.

According to the allostatic load model, the effects of stress are cumulative. Exposure to stressors activates the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axis (SAM) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. SAM releases the catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal glands. Meanwhile, the HPA releases glucocorticoids, like cortisol, which are steroid hormones. This physiological stress response helps us respond and adapt to stress. In fact, it’s remarkable how much stress we can bear. But it’s not without consequence.

Over time, these physiological adaptations to stress cause significant wear and tear on your body that can negatively affect your immune system, metabolic processes, and your cardiovascular system. In other words, allostatic processes lead to increases in blood pressure, lipids, glucose, and inflammation, which increase health risks.

Allostatic overload occurs when the cumulative effects of physiological stress response lead to health problems, disease, or death. This is why it’s estimated that stress plays a role in anywhere from 50 to 70 percent of all physical illnesses.

Given these cumulative effects of stress, I’m sure you see why I’m worried about the millions of Americans simultaneously coping with multiple stressors. These include pandemic stressors like job and other economic loss, trauma from illness or witnessing illness, and bereavement. It also takes a lot of adaptive energy to adjust to the new, but necessary, “COVID-19 normal” that’s altered our routines and ways of meeting our needs. It’s necessitated adjusting to a social environment dramatically altered by facemasks, social distancing, and other people as a health threat. Meanwhile, many thousands of people simultaneously experienced the threat and consequences of other disasters like flooding, wildfires, hurricanes, and other extreme weather events. And of course, occupational, relational, and political sources of stress haven’t exactly gone on holiday.

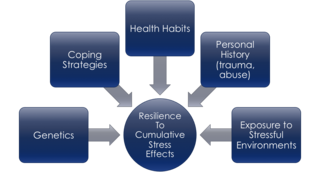

Your resilience—that is, your ability to adapt well to stress and avoid allostatic overload—is partly determined by factors outside of your control. Some people are more vulnerable to allostatic overload due to genetics or past trauma and abuse. Long-term exposure to environmental stressors like noise and crowding and to personal stressors like financial, family, or health problems, also increases vulnerability to health impacts from allostatic overload.

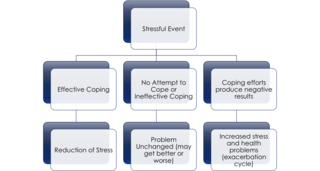

But it’s not entirely out of your hands. Healthy coping strategies like humor, meditation, getting into nature, exercise, spiritual practice, and cognitive reframing (e.g., “This too will pass, it’s temporary”) help. Less helpful is relying too heavily on strategies like venting, denial, distraction, stress eating, and alcohol and drug use. It’s okay to give yourself some leeway; after all, these are tough times. But you don’t want your coping strategies to spawn problems of their own or weaken your body’s resilience. The stronger you are, the more likely it is that your body can weather ongoing stress, and the less likely it is that you’ll get sick or burned out. Consider whether your substance use, stress eating, or distractive entertainment is entering into unhealthy territory. If yes, create a plan for managing your stress and meeting your needs in healthier ways. Reach out for help if you need it.

Allostatic load theory reminds us that the effects of stress accumulate over time and lead to poor health. But building your resilience can reduce health impacts. Review the stressors in your life and if possible, take actions to reduce them. And, because your health practices and your coping strategies make a difference in your resilience, tune them up so your body can better withstand the impacts of stress.

References

American Psychological Association (2012). Building Your Resilience.

Bonanno, G. A., Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K., & Greca, A. M. L. (2010). Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(1), 1-49.

Juster, R. P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 2-16.

Wiley, J. F., Bei, B., Bower, J. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2017). Relationship of psychosocial resources with allostatic load: a systematic review. Psychosomatic medicine, 79(3), 283-292.

Walker, D.D., Jaffe, A.E., Pierce, A.R., Walton, T.O., & Kaysen, D.L. (2020). Discussing substance use with clients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A motivational interviewing approach. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12, S115-S117.