Mindfulness

What Is Mindfulness and How Does It Work?

Mindfulness is one of the most important developments in the past 20 years.

Posted February 6, 2015 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

It is readily arguable that the single most significant development in mental health practice since the turn of the millennium has been the widespread emergence of mindfulness-based approaches. They are popping up everywhere you look. Type “mindfulness” into Google and you get 27 million hits.

There are mindfulness based-treatment approaches for pain, depression, anxiety, OCD, addiction, PTSD, borderline personality, and on and on. There are also mindfulness centers and clinics, and there are now educational and training programs for prisoners, government officials, sports professionals, business leaders, and many other groups. It is also a hot commodity in schools. In 2012 Tim Ryan, a Congressman from Ohio, published A Mindful Nation, and received a $1 million federal grant to teach mindfulness in schools in his home district.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the surge of mindfulness-based approaches has come with critics, some of whom have coined the term “McMindfulness” to highlight the simplistic and commercialized nature of many programs, claims, and offerings.

There is no cheap and easy pathway to mental health and fulfillment, and critics are right to raise cautionary flags about mindfulness being a panacea. Nevertheless, mindfulness has caught on for good reasons, and there are genuine insights to be had. The point of this blog post is to help readers understand what mindfulness is and to provide a basic framework for how it works from the perspective of a unified view of human psychology.

Rooted in Buddhist traditions that emerged thousands of years ago, the modern mindfulness movement in the West was largely sparked by the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, who developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, starting in 1979. His work was initially focused on helping patients deal with chronic pain. The problem was that patients would work to mentally escape or avoid the pain, but ultimately this inner struggle would create more problems and mental distress and exhaustion. By adopting a mindful approach to pain, Kabat-Zinn found he could relieve mental distress and improve functioning overall.

In the next decade or so, mindfulness became integrated into cognitive and behavioral approaches. Some prominent ones included approaches such as Marsha Linehan’s Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Steve Hayes and colleagues’ Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and Segal and colleagues’ Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy.

But cognitive behavioral folks weren’t the only ones paying attention to mindfulness. Richard Davidson’s work in affective neuroscience forged a link between mindfulness and the brain. Mark Epstein’s book, Thoughts Without a Thinker, offered an early bridge between mindfulness and a psychodynamic perspective. More recently, the interpersonal neurobiology movement led by individuals like Dan Siegel and Allan Schore offers an integrative, brain and attachment-based view of mental functioning that has mindfulness as a core principle. Emotion-focused perspectives, like that of Les Greenberg, also offer a perspective that is highly consistent with mindfulness-based teachings. Finally, the positive psychology movement, with its focus on growth and optimal functioning, has also raised the mindfulness banner (see, e.g., Todd Kashdan’s work).

Given all this interest and support across such a wide variety of traditions (not to mention the fact that it has been a central element of a major spiritual/philosophical position for thousands of years), it seems safe to say that there must be at least something to mindfulness that is of deep value. Indeed, there is. But what, exactly, is it and how does it work?

To answer this question, one needs a working theory of human consciousness. And, this is, in my opinion, what is often missing from educational and training programs about mindfulness. Thankfully, the unified approach comes with a working theory of human consciousness that can frame the issues for us in a way that allows us to understand why a mindful approach is generally associated with greater psychological health and why defending against experiences creates disharmony in the long haul.

First, let’s start with the basics. There are two key ingredients that form the foundation of all mindfulness-based approaches: awareness and acceptance. To foster awareness, folks are taught to expand one’s attention to one’s inner processes and experiences, especially of what they are experiencing in the here and now. Perhaps the most famous mindfulness-based exercise was developed by Kabat-Zinn and involves eating a raisin. Although normally we pop raisins (or whatever) into our mouth without thinking too much about it, the raisin exercise slows the process down enormously and teaches individuals to attend to the look, feel, weight, taste, and texture, along with whatever thoughts flow in association, to make the point that our attention can be focused on many different possible streams and that, with training, one can expand one’s conscious attention and learn to focus it as necessary. The second key ingredient, in addition to expanding awareness of one's present experience, is the ingredient of acceptance—mindfulness practices teach individuals to learn to observe and accept the streams of thought and experience that run through their mind.

Thus, mindfulness is very much about inner awareness and acceptance (sometimes this expands to interpersonal mindfulness—i.e., the minds of others). From a unified approach, this is suggestive of helpful things, as awareness and acceptance (in addition to active change) are seen as some of the key ingredients for adaptive growth. But here is the rub. There are some things—maybe even many things—that we don’t want to think about or attend to. We don’t want to think about our insecurities or our selfishness or our failures or our fears of rejection or abandonment. We don’t want to realize we are questioning our purpose in life or feel the fear that our existence is really meaningless. We don’t want to remember the trauma or the dark years of our past, or attend to our feelings of rage and despair. After all, isn’t the secret to a happy life just deciding to be happy and think positive thoughts?

No. That is not the secret. Indeed, if followed rigidly and defensively, that is a pathway to potential disaster. But why? To answer this question and to understand why mindfulness is an important skill that is crucial to mental health and avoiding vicious neurotic cycles we need to be clear on the elements and domains of human consciousness.

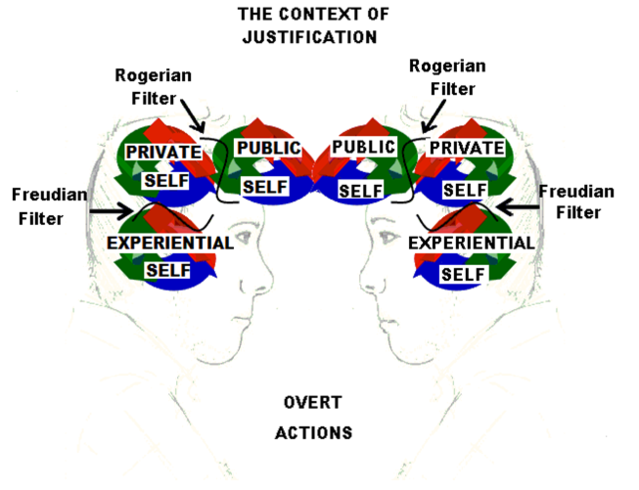

As illustrated in this diagram, the unified approach points out that there are three domains of human consciousness. A central principle is that mental health depends on individuals is getting their basic, core psychosocial needs met and have a relative degree of harmony between these domains of consciousness. Thus, central to understanding the utility of mindfulness involves understanding these domains and their interrelations.

The first domain of consciousness is the experiential domain (labeled above as "experiential self"). This is the part of you that comes “on line” when you first wake up and goes off line when you sleep. This is the first-person experience of being, and is sometimes referred to as your “theater of consciousness.” Using the theater stage metaphor, attention can be the term for what is brought on and can be held on stage. Thus, the raisin exercise is helping people recognize that by gently guiding your attention, you can bring many otherwise hidden (or backstage) elements to the front and center.

The second domain of human consciousness is the private self, which is your internal narrator. This is the self-talking portion of your consciousness system, which translates what is happening and why into language-based representations and provides the narrative for what you ought to be doing given your worldview, self-concept, and understanding of the current situation.

The third and final domain is the public self or persona. This is what you show other people through your overt words and actions. It is the image you try to maintain to others (even though it might be quite different than how other people see you).

In addition to these domains of consciousness, there are filters between them that need to be considered. First, there is the “attentional filter,” not shown in the diagram but alluded to earlier, which exists between unconscious processes and your experiential consciousness. Staying with the theater metaphor, this is the filter between what gets on your “theater” and how much stage time it gets versus what stays “backstage” in the unconscious.

The unified approach refers to the next filter, the one between the experiential consciousness and the private self, as the Freudian filter. If you wonder whether or not you have a Freudian filter ask yourself the question: “Have you ever told yourself not to think about something or intentionally directed your attention toward something else because you did not want to think or feel something?” The vast majority of people answer: “Yes, I sometimes do that!”. That is called suppression, and it is one of many such filtering mechanisms, many of which are not explicitly conscious. For example, there is an entire line of work in social psychology called cognitive dissonance which maps how the internal narrator works to alter and filter experiences to make them consistent with the “story” that one is a good, reasonable and effective person.

The third filter is called the Rogerian Filter. This is between the private narrator and the public persona. Its operations can be seen when thinking about what it is that folks try to keep from others, either directly via lying and deceit or more indirectly via shifting the conversation or actions to divert another’s attention and manage one’s impression. When you reach for your phone to appear busy when you are sitting alone at a restaurant because you don’t want to appear lonely or isolated, you are engaging your Rogerian filter. When you tell a friend her new haircut looks “fine” when you think it looks horrible, you are engaging your private-to-public filter. Or, more to the point, when you say you are “fine” to a friend asks if you are ok because you don’t want to burden them with your misery, you are engaging your private-to-public filter.

With this map of human consciousness in place, we can now begin to understand mindfulness. Indeed, it is through this map that we can begin to understand how mindfulness might work because it offers a framework for understanding why we might be hesitant to be mindful.

Consider, for example, the following scenario, one that parallels several stories I have heard as a clinician: Janet, a 16-year-old high school girl, goes to a party. She is an immature drinker and six drinks in Janet finds herself highly disinhibited and flirting and making out with an attractive guy she just met. Three more drinks and her conscious control is fading fast. She is ready to leave and head home and go to sleep, but he is also drunk and starts forcing himself upon her and ten minutes later she has lost her virginity. Shocked, dazed, inebriated, and confused she gathers her stuff up and heads home. Waking the next morning, the party is a fog and she is left with fuzzy images of him forcing himself upon her and other evidence of the event, but much that remains unclear.

A part of her emotional system will powerfully register the rape. She was victimized and violated in the most intimate way and that has huge emotional implications. As Janet’s emotional system starts to send alarms about the assault, these alarms cause all sorts of “trouble” for the narrator portion of her mind, the one that has to determine what exactly happened, what was justifiable, what was not, and what should she do about it. Because of the excessive alcohol consumption, the actual details are fuzzy in her mind. Is she certain it wasn’t just a bad dream? Did she really say “no”? Did he really force himself on her or was she really just paralyzed and did not say or do much of anything? Then thoughts of guilt and self-blame flood her mind: “How could I get that drunk?” and “What was I thinking?” and “My parents cannot find out about this, they will go crazy”. The flood of all the implications begin to hit her and she starts to really become unglued. In short, if she allows herself to be “mindful” of the emotional experience, she will become completely dysregulated and who knows where this will end up? So, what does she do? She dissociates and avoids. Her narrator and other filtering defenses kick in and she does whatever she can to put it out of her mind. Essentially her psychological system “decides” the best way forward is to pretend it never happened. This example should provide a clear depiction of why being “mindful” is not always easy and often does not feel like the best way to be.

Or consider a less dramatic, but still very relevant example. Jeff is a graduate student in biology. He was pleased to get into grad school, but two months in he is feeling quite stressed. He is constantly wondering if he is as smart as the other students, but tries to push these thoughts out of his mind. Always a high achiever, Jeff gets his midterm back and discovers his B-, which is an almost failing grade in grad school, is the worst performance of the ten students in the class. Panic surges through his system. He feels he is about to be revealed for the failure he has always feared he would be. Memories of him “faking it” to appear smart and small incidents that "revealed" he really wasn't flood him. His narrator splits. One voice is dark, telling him he is, deep down, fundamentally incompetent. The other voice is weakly hopeful, telling him not to over-react and that he must not think like this. Then he looks around and fears others are noticing his emotional reaction. Embarrassed, he decides he must pull it together, that he must stop thinking and feeling this way, so he stuffs his feelings and goes home and pours himself into studying for the next test.

The stories of Janet and Jeff remind us why humans often are not mindful, and why it makes perfect sense that folks sometimes try to put stuff out of their minds. But their stories also point to why avoidance of painful feelings and thoughts so often lead to greater suffering. Janet’s trauma did not disappear, nor did Jeff’s fear that he was not smart enough. Rather they are now episodic memories and have associated thoughts and experiences that have to be walled off from consciousness (i.e., brought onto the stage).

We can infer from our model of human consciousness that as more and more memories are avoided and split off, an individual’s psychological system becomes increasingly destabilized, vulnerable, insecure, and defensive. It can get to the point for some folks where virtually any event triggers an association of a thought, feeling or memory that must be avoided. This results in chronic anxiety, defensiveness and, over time, depression. Thus, via this model and analysis, we now have clues as to how mindfulness, if done in a sophisticated way, can help people from getting all tangled up inside and potentially result in more mental harmony.

I will end this rather lengthy blog with some commentary about where I find it useful for folks to head when considering mindfulness. The first consideration is to remember what the Buddhist “discovered” such a long time ago: Life entails suffering and that much suffering is inescapable. Indeed, to be alive is, in part, to suffer, at least some of the time. Mindfulness emerged because the Buddha realized that attempts to escape suffering, to put suffering out of our minds, to banish it to the nether regions, almost always backfire in the long run. Doing so often produces mental disharmony and sets one up to be in chronic fear of one’s own memories, feelings, and experience.

Second, the goal of mindfulness is to cultivate a meta-perspective on one’s consciousness and personhood that can foster greater mental (and relational) harmony. This is the position of seeing one’s self (and others) as a human being, trying to do the best they can. I try to capture the desired attitude of this observer position with the acronym C.A.L.M.* The “C” stands for curiosity, a stance of wondering what thoughts and feelings are present and where they come from, thus cultivating as much awareness as possible. The “A” stands for acceptance, which means that whatever flows through one’s stream of consciousness will be taken in and accepted rather than denied and rejected. The “L” stands for an attitude of loving compassion for one’s self (and others). And finally the “M” stands for Motivated to learn more and to seek to do so from a position of security. By this I mean a cultivating an openness to additional experiences and insights, and doing so from a centered position of balance and resilience.

I believe that mindfulness is an important development in mental health and largely am happy that it is attracting the attention it is. I further believe the benefits of mindfulness are greatly enhanced when it is accompanied by deeper understanding of human consciousness and the human condition. Such a perspective can help to ensure that applications of mindfulness are done, well, mindfully.

---

* I borrowed and altered this acronym from mindfulness expert Dan Siegel, who uses the acronym COAL, which stands for Curiosity, Openness, Acceptance and Love to describe this position. I found CALM a more appropriate word than COAL to capture the position, but I am indebted to him for the idea.