Bias

Do You Have a Racism Blindspot?

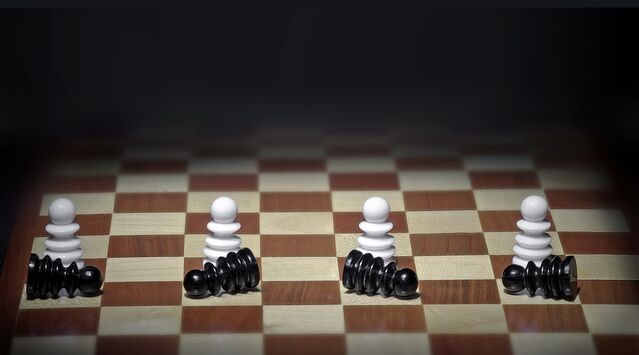

People have a blindspot that prevents them from seeing their own racism.

Posted July 7, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

According to Google, internet searches for the phrase “Am I racist” have hit an all-time high. In the past month, articles with this phrase in the title have popped up at CNN, The Hill, Thrive and Medium. It seems that now more than ever, people (especially White people) are turning their gaze inward and asking this important question.

Asking “Am I racist?” provides a good first step in the quest to eliminate racism, but it doesn’t guarantee actual change. That’s because there are powerful psychological forces at play that prevent people from seeing their own racism. As a psychological scientist, I have studied racism for over two decades, and the thing that strikes me over and over about racism is how people go to great lengths to deny they are racist, even when their behaviors clearly suggest otherwise.

Often, people who have been publicly caught committing an act widely perceived as racist later claim, “I’m not a racist.” Whenever such an instance occurs, the question I always have is this: Are racist people who insist they are not racist lying to us (meaning they know they are racist and don’t want to admit it), or are they lying to themselves?

Determined to find an answer to this question, my graduate student Angela Bell and I designed a series of experiments. At the beginning of the new school semester, university students are required to fill out a long online questionnaire that is used for various studies throughout the school year. Capitalizing on this requirement, we hid within these surveys a list of behaviors and asked respondents to simply indicate if they had ever committed the behavior in the past. Half of these behaviors were undesirable but non-racist actions, such as lying to get out of a gathering with friends or family, or wearing the same underwear two days in a row. The other half were explicitly racist actions, such as using the N-word to refer to Black people, laughing at another person’s joke about Asian people, or avoiding interacting with a Muslim person out of fear.

Several months later, we invited these same participants into the lab for what they thought was a totally unrelated study. They were told they would be reviewing the responses of a randomly selected student, but in reality, they viewed their own responses that were under the guise of another person’s name.

Now I know what you’re thinking—did any of these participants see through our rouse and realize this “other person” was really themselves? We didn’t think they would since students complete tons of studies each semester and it's easy for them to forget the details. But just in case, we asked everyone about this at the end of the study. In fact, only one student out of 131 realized the truth (that person was of course removed from the analyses).

Now back to the study. Participants were shown a list of behaviors supposedly committed by this “other student” and then were asked two key questions: (1) how racist they thought this “other person” was compared to their average fellow student and (2) how racist they themselves were compared to their average fellow student. Notice that by comparing these two responses, we were able to subtly measure how racist these participants thought this “other person” was compared to themselves.

So what did we find?

Participants consistently rated themselves as less racist than this “other person,” even though this “other” committed the same acts they did. This pattern suggests that we may be able to accurately assess another person’s level of racism, but we suffer from a psychological blindspot that prevents us from seeing our own racism. When we observe other people engage in racist behaviors, we label them as racist. But when we engage in those same behaviors, we fail to label ourselves as racist.

To determine the robustness of this effect, we conducted two additional studies using the same design. The blindspot pattern replicated in both cases. Furthermore, we found this racism blindspot remained even when we reminded participants their responses were confidential and they didn’t need to worry about political correctness.

So although people may be asking the question “Am I racist” more than ever, there’s a good chance that after deliberating, they will still conclude they are not.

Why do we have this blindspot? More research on the topic is needed to definitively answer this question, but one clue can be found in research on the better-than-average effect (BAE). The BAE is just what it sounds like—a tendency for people to consistently rate themselves better than average on nearly every trait, from driving and physical attractiveness to morality. This of course defies logic, since by definition the majority of people are “average.”

Decades of research on the BAE shows that when people assess their own traits, they base their judgments on peak positive performances (“I’m a better-than-average baseball pitcher because I played that no-hitter game last year”). But when people assess someone else’s behavior, they base their judgments on an average of all performances (“Sure, she pitched that no-hitter once, but her overall pitching average is not that great”). In essence, we use two very different psychological processes when judging ourselves versus others.

Something similar could be happening when we make assessments of racism. When we ask ourselves “Am I racist?” we likely think of the times we behaved in a non-racist, egalitarian way and weight these few instances more heavily when making our assessment. But when we ask ourselves “Is she/he racist?” we look at the behavioral evidence more even-handedly.

The bad news is that blindspots are hard to overcome. It’s hard to change something that you cannot see. But knowing you have a blindspot is the first step in overriding this bias. Another good step is listening to those around you. If someone accuses you of saying or doing something racist (or sexist or homophobic), your first gut response will be to deny it. “I’m not a racist, I’m a good person,” you may say, or “I’m a liberal, I can’t be racist.”

Instead, force yourself to stop, take a pause, and really assess your behavior. Ask yourself, “If I saw someone else do the exact same thing, would I consider them racist?” Chances are, you would.