Depression

A Renaissance Secret for Overcoming Depression

A 400-year-old book could offer lessons for modern minds.

Posted October 16, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Far from being a disorder, depression might be your brain’s signal that something in life isn’t working out.

- The idea of depression as a message, rather than a malfunction, stretches back to the Renaissance.

- Recent evidence backs up a theory by theologian Robert Burton, and may have powerful benefits for therapy.

At 16, I was diagnosed with depression and hospitalized for six weeks in an adolescent psychiatric ward. I was taught that my depression was a chemical imbalance, and that drugs like Prozac somehow reversed that imbalance.

It would be nearly 30 years until I discovered that the chemical imbalance theory of depression was essentially groundless. I also learned that framing one’s depression as a brain disorder has its own harms.

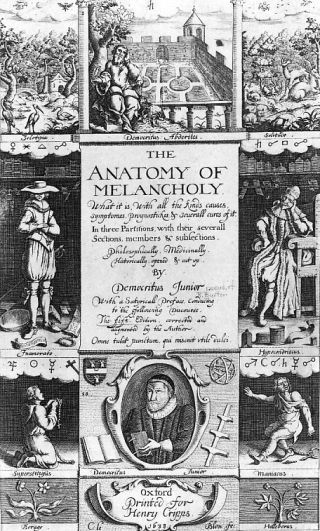

But if it’s time to move past the “chemical imbalance” metaphor and its harmful effects, what should we replace it with? I recently found a possible answer to that question in a 400-year-old book, The Anatomy of Melancholy.

A Renaissance Masterpiece

The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in 1621, is the strangest book I’ve ever read. Part science and part sermon, it’s a guidebook for overcoming “melancholy,” the precursor to our modern idea of depression.

It’s also massive. The fifth edition runs to about 500,000 words. That’s about two-thirds the size of the King James Bible. Its author, the British scholar, philosopher, and theologian Robert Burton, wrote the book to battle his own melancholy.

The Anatomy begins by listing everything that, at the time, was thought to cause melancholy. Sometimes, Burton thought, it’s imbalanced body fluids. Sometimes it’s defects in the parents’ sperm or egg. Or demon possession. Or polluted air. Or heartbreak. Or wickedness.

But regardless of the cause, the solution was always the same. It’s a solution that modern psychiatry is only now rediscovering.

What if depression is trying to tell me something? What if it’s trying to alert me to the fact that something in my life needs more attention?

If so, the answer isn’t always pills. It’s to listen to what it’s trying to say.

A Modern Prescription

Forty years of medical psychiatry—and its mantra that mental health problems are like physical diseases—has blinded some of us to Burton’s simple, plausible idea. What if depression is designed, not diseased? What if it’s purposeful, not pathological?

Think about fever. Until the 1700s, doctors “knew” fever was a disease. One needed to fight it with drugs and bleeding. Now we know that fever isn’t a disease at all. It’s part of your body’s design for fighting infection.

Seeing fever as designed, not diseased, changes everything about how we treat it. The answer isn’t to blast it with medications but to help it reach its natural end, while comforting the patient in the process.

Burton thought of depression more like fever than fibromyalgia. The trick is to learn to hear it out. But if depression is a message, what’s it trying to say?

A Game-Changing Paradigm Shift

According to the modern school of evolutionary psychiatry, depression is trying to tell me that something in my life isn’t going well and needs more attention. Maybe it’s a career goal. Maybe it’s a relationship. Maybe it’s a life plan. Maybe depression is even a protest against the demands of making a living in an increasingly materialistic society.

The theory that depression is a signal, rather than a dysfunction, not only explains a broad range of facts about depression. There’s even evidence that simply thinking about depression as your brain’s wake-up call, rather than a chemical imbalance, may have powerful therapeutic benefits.

Hans Schroder, Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and clinical psychologist at the University of Michigan, and his colleagues recently studied the effects of thinking of depression as the mind’s natural signal, rather than a brain disorder. People who adopted the signal perspective tended to feel less helpless about their depression, more optimistic about therapy, and less stigma about their condition.

That’s not to say medication has no role in depression. It seems to help some people manage unbearable feelings, even if we don’t know why. Without being able to manage those feelings, it can be hard to reflect clearly on what the problem might be. But they needn’t be the first line of attack.

For many, a better solution would be to find a counselor, guide, or therapist who has a similar viewpoint on depression, and who’s willing to help figure out what it’s trying to say.