Politics

Who Are the Most Negative Voters?

Surprise, independents are more negative than even extreme partisans.

Updated September 20, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Negative voters cast ballots against rather than for a candidate.

- Independents are more negative in voting than partisans.

- Independents are more susceptible to negative ads than partisans.

By Joesph J. Siev and Richard E. Petty

Voting against a despised candidate rather than voting for a favored one has increased considerably in the U.S. over the past few decades. Political scientists captured this in their 2017 headline from Politico.com: Negative partisanship explains everything.

Echoing this, the New York Times Magazine noted in 2020 that the current era is “one in which political allegiances are determined less by affection for one party than by hatred of the other.”

Negative partisanship has become a popular way to explain what has gone so wrong in American politics, but it has also received some criticism lately.

For example, a paper published in 2022 showed that positive partisanship, where political allegiances are determined more by positive feelings for one political side than negative feelings toward the other side, is still more prevalent than negative partisanship overall. So, who is responsible for the rise in negativity in politics?

Negative partisanship is more common among political independents

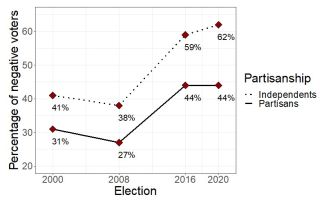

In a novel analysis of existing survey data over the past two decades, we found that it is people who do not identify as Republicans or Democrats—that is, independents—who are more likely to be negative voters. As the number of self-identified independents in U.S. politics increases, so too does the incidence of negative voting.

But, why are independents more likely to be negative voters? Consider what it means to identify as a partisan versus an independent. When asked how they think about politics, partisans give an affirmative response. They stand up to be counted and say, Yes, I am a Democrat or Republican.

But independents don’t do this. Keep in mind that most independents prefer one party over the other. These are sometimes called independent leaners, as opposed to true independents, who do not prefer either party. So, most independents know which party they would identify with but they refuse to do so, saying “No, I am not a partisan—not even on my preferred side.”

This basic difference in positivity-versus-negativity between partisans (I am X) and independents (I am not X) carries through and affects their attitudes and behavior in various ways, such as negative voting.

Today, independents are more likely to vote against versus for a candidate

In a study mentioned above, we analyzed nationally representative data from the Pew Research Center collected before four recent presidential elections (between 2000 and 2020), and we found that independents were more likely than partisans to say they were voting against the presidential candidate they disliked versus for the candidate they preferred. Most independents voted against it in recent elections, whereas most partisans still voted for it.

The proportion of independents is related to the amount of negative voting

Our findings have some other interesting implications. First, the proportion of people identifying as independents says something about how widespread negative voting is at any given time. This might help to explain why political polarization has been getting worse. That is, the rise in negative voting and the increasing number of independents are connected.

Independents fall for negative campaign advertisements

The difference in orientation (being against versus for) also impacts how independents and partisans react to campaign advertising. In several studies, we found that whereas partisans agreed more with requests to support their party, independents agreed more with requests to oppose the other side.

Our research suggests that perhaps all of the negative advertising each campaign season might be especially impactful on independents. This insight could be useful for political marketers, helping them tailor communications to different groups of voters.

Independents are also more negative than partisans in non-political domains

Finally, our findings say something broader about the meaning of partisanship and independence. Specifically, we found that the same thing occurs even in several non-political domains where it could make sense to think of oneself as an independent.

For example, in professional sports rivalries, independent fans (who do not identify with either of the two competitors) were more likely than partisan fans (who identify with one of the competitors) to root against rather than for a team. This generality suggests that although negative partisanship has important consequences for political behavior, it is not caused by political factors.

Negative independence

Self-identified independents are often overlooked in political research because, in many ways, independent “leaners” behave like partisans. But our findings highlight one way in which independents—even leaners—are not like partisans: Independents are more likely than partisans to adopt and endorse negative, opposition-based ways of framing and expressing their preferences.

Conclusions

Don’t let the terms confuse you: Negative partisanship and negative voting are more prevalent among independents, not partisans. Independents are also more susceptible to negative advertising than are partisans.

Joe Siev is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Consumer Behavior at the University of Virginia Darden School of Business. Richard Petty is Distinguished University Professor of psychology at Ohio State University.

References

Siev, J. J., Rovenpor, D., & Petty, R. E. (2024). Independents, not partisans, are more likely to hold and express electoral preferences based in negativity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 110, 104538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2023.104538