The dating/hook-up megalith Grindr came under fire earlier this year for including an ethnicity filter. Users were previously able to add an ethnicity filter to their searches, excluding romantic prospects based on their racial background. However, amid a backlash of accusations of racism and algorithmic bias, in June this year, Grindr vowed to remove the ethnicity filter from the next version of the app.

While change is change, many users suggest that it is long overdue. For years, LGBT people of colour have flagged the issue with Grindr but until recently had received no response. Some angrily point out that Grindr didn’t even take the issue seriously until posts by gay white men received a lot of attention on social media.

Grindr’s removal of the ethnicity filter is proof that gay communities (and consequently corporations that want their business) are increasingly aware of how explicit sexual racism can hurt racial minority members. Unfortunately, while men on Grindr are now unable to filter by racial background and it is commonly considered socially unacceptable to explicitly discriminate on dating apps, the fact is that many gay men unapologetically romantically fetishize or exclude people based on race.

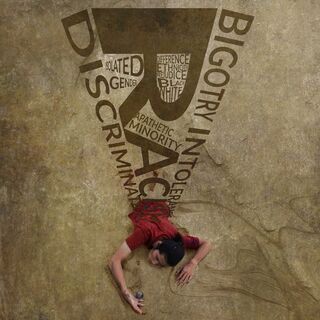

Sexual racism is a term that broadly refers to discrimination in romantic partner selection on the basis of perceived racial identity. Sexual racism can be either explicit or implicit. Explicit sexual racism can be thought of as overt romantic discrimination (e.g. expressing a preference for certain racial backgrounds on dating apps), whereas only dating people of a certain racial background or excluding people of a certain racial background is implicit sexual racism. While a problem in both heterosexual and gay dating, sexual racism impacts gay racial minority members much more as the dating pool is much smaller. When it comes to dating, gay men also place more of a focus on race than their heterosexual counterparts. Previous studies have found that in Australia, only 42 percent of gay men were attracted to men of all racial groups.

Asian men in western gay communities are particularly impacted by sexual racism as they are generally the least desired. These men often internalize racialized stereotypes about other racial groups, leading to a preference for white partners. This combined with the lack of demand for Asian men leads to many Asian guys vying for the attention of relatively few white men with a preference for Asians (known pejoratively within the gay community as "rice queens"). Sometimes they must forgo the types of sex they wish to engage in, in favor of meeting sexual expectations to gain access to partners. Research suggests that this leads to feelings of expendability, inequality, and racialized sexual objectification in relationships with so-called "rice queens." The scarcity of white men seeking Asian partners and internalized racism among gay Asian men often leads to feelings of competition between them for white partners, while rarely seeing each other as potential partners. This can impede the formation of healthy racial and ethnic identity, important in maintaining self-esteem and self-worth for racial minority members. This makes it more difficult for gay Asian men to come to terms with both their same-sex attracted identity and their Asian identity, which often negatively impacts their well-being.

Through the Graduate Diploma of Psychology-Advanced (GDPA) program at Monash University, my colleague Christopher Lim and I sought to investigate the phenomenon of sexual racism within the gay community. More specifically, we looked at whether or not gay Asian men cared about the racial preferences of potential partners in online dating. We recruited 127 Asian men who have sex with men (MSM) and had them view a number of hypothetical dating profiles before answering a series of questions about each (e.g. "How desirable do you find this man," etc.). Half of the profiles they viewed were Asian, half were white, but all were of men. Additionally, one-third of the profiles gave the information that the man in question had no dating racial preference; another third suggested that he only dates white men; and the remaining third described the man as only dating Asian men. It should be pointed out that we specified the racial preference by suggesting that it was inferred from checking out the man’s Facebook profile (it was not stated directly). We did this to better simulate implicit rather than explicit racism. In order to control for immediate visual appeal, all photographs of men were similar in attractiveness.

We found that our participants didn’t romantically favor Asian men over white men or vice versa. In other words, the ethnicity of a prospective partner didn’t by itself make any difference to how desirable he was. However, the racial preference of a prospective partner made quite a big difference. We found that our participants desired potential white partners most when they exhibited no racial preferences, compared to having exclusive preference for men or white men. We suggest that this is due to many gay Asian men having negative attitudes towards "rice queens," reflecting an awareness of the negative effects of racial fetishization and unequal power dynamics between white and Asian gay men in partner selection.

Additionally, our participants likely were put off by being sexually excluded by those expressing interest in only white partners. Potential Asian partners were most attractive when they had no racial preference or a preference for other Asian men (compared to a preference for white men). While white preference for Asian partners is commonly framed in the context of racial fetishization, Asians having a relative preference for other Asians has been conceptualized by some as a challenge to the racial hierarchy and a rejection of white/Asian racial power dynamics. Those with a preference for white men were less desirable than both those with no racial preference and those with a preference for other Asian men. This is explained by previous research which has found that despite many Asian MSM having a preference for white partners, most have negative attitudes towards other Asian men who only desire white partners, reflecting feelings of competition between Asian men for white partners.

Grindr’s removal of the ethnicity filter and research such as ours suggest that there is strong opposition to explicit sexual racism, especially among members of marginalized minority communities. A practical implication of our study is that omitting racial preferences from online dating profiles can have benefits for one’s desirability (or at least it won’t have a negative effect). This could also reduce feelings of exclusion or marginalization among racial minority members.

As noted earlier, overt sexual racism online is increasingly considered to be socially unacceptable, and men mostly don’t communicate their racial preferences in obvious ways. Reducing overt racism on online dating applications will improve the experience of racial minority members, but does little to address the systemic issues underlying their disadvantaged status in partner selection. According to past research, one thing that racial minority men can do to mitigate the effects of sexual racism is to date other racial minority men and try to not see each other as competition. While this isn’t for everyone, seeking out other racial minority men as friends or attending relevant gatherings could provide men with a support network of people who have experienced similar stigma due to sexual racism.

The study is currently under peer-review.