Adolescence

How Change Drives the Parent-Adolescent Relationship

Five dynamics of change that can challenge how parent and teenager get along.

Posted June 24, 2019

A way to think about adolescence is simply as one example of human change – that larger process of redefinition that continually keeps upsetting and resetting the terms of everyone’s existence all their lives.

Change sees to it that within us, between us, and outside of us, nothing remains exactly the same for very long. Partly chosen but mostly un-chosen, in one form or another, change plays a leading role in how human lives unfold.

Operationally, change is in evidence when some condition or circumstance stops or starts, increases or decreases, thereby disrupting the fixed, familiar, customary, normal, stable, routine, or established operation of our lives.

Any major life change usually turns out to be some compound of all four kinds of change. For example, when a couple has a first child, that change event can feel revolutionary:

- they must stop just managing themselves and only thinking about each other,

- they must start inhabiting parental roles and sharing child-care responsibility,

- they must increase their family expenses and household demands to be met,

- they must reduce old social freedom enjoyed before parenthood began.

Change can make life challenging and interesting and chaotic and painful. Coping with change is what everyone must learn to do.

What follows are five dynamics of change that can impact the parent/adolescent relationship.

1) Change begets change.

Although it’s easy for parents to think that adolescence is a one-sided transformation – the young person doing all the changing – this is not the case. Years ago a young teenager set me straight about the mutuality of adolescent change when I asked how he could tell his time for growing up had begun. “By how my parents have changed!” he immediately responded.

“How’s that?” I asked, surprised.

Then he explained. “They used to be fun-loving, relaxed, and easy going, but now they’re more serious, complaining, and tense to be around.”

The young man wasn’t lying. Adolescence is as much about adult change as about child change because as adolescence changes the child, the parent changes in response, and now the relationship between becomes altered, gradually growing them apart, as it is meant to do.

Growing up transformations can be hard on the teenager, but as hard for the parents is being taken through all those adolescent changes. "A new love interest begins!" Then, of course, there are those occasions when adolescents feel “yanked around” by unwanted family changes that dramatically alter their existence – like a geographic family move, parental divorce, or remarriage. “Parent changes change your life!”

2) Change incurs loss.

Change can be expensive. To begin anything new and different, something old and familiar must usually be let go. So it is with adolescence, which begins with the child’s separation from childhood, usually around ages 9 to 13. Now in words and actions, the young person declares, “I'm no longer content to be treated and defined as just a little child anymore!” And in this proud determination, the young person sustains two losses.

First, they have to let go of some childhood activities and objects (like playing familiar games and with beloved old toys.) Second, they have to let go idealizing their wonderful parents who become unwelcome gatekeepers of more teenage freedom now being sought. “My parents keep getting in the way of what I want to do!”

Their adolescent's childhood can be a lot for the parent to give up, too.

Years ago, a mom described losing her child son to adolescence in these words: “When I look back at our childhood time together, he was always standing next to me and with a big smile on his face, usually with his arm wrapped tightly around me, and with a big smile on his face. Fast forward eight years, and while I know he still loves me, I have felt so rejected by my son… He seems uncomfortable with any physical affection from me 90% of the time and wants to spend less and less time with me or even around me. My rational brain says that if my 16-year-old son wanted to be with his mom 24/7, and was hanging on me constantly, we might have a problem. However, my emotional brain, my ‘mom’s brain,’ still thinks of him as that sweet little loving boy, and I have taken everything so personally.”

She is both struggling with letting go, and with being let go. Change is merciless: the mom will never have her adoring and adorable little boy again, just like the father who grieves the adolescent loss of “daddy’s little girl.”

Not only does adolescence begin with loss of childhood for the parent, but it also ends (some 10 to 12 years later) with the empty nest – a daughter or son moving out to establish independence from family. Laments the bereft adult: "Am I supposed to stop parenting now?"

3) Change violates expectations.

People create mental sets like expectations to help them move through change and time with some sense of what circumstances or events they can anticipate. To have no expectations can be unnerving, even frightening: “I have absolutely no idea what’s going to happen next!”

A growing adolescent is no longer a little child, and parents need to factor this reality into what they now anticipate. Their expectations of adolescence can have emotional consequences. To the degree their expectations fit the changing reality they get, parents can feel forewarned and prepared. To the degree those expectations do not fit the reality they get, parents can become at risk of overreacting. “I keep losing it as my teenager keeps surprising me!”

To prevent such overreaction, it generally behooves parents to adjust their expectations to fit the changing reality of adolescent development. Put another way, to keep up with their teenager, they need expectations that keep ahead of the growth curve. Thus if they anticipate that the adolescent may become somewhat more distant than the child, that the adolescent may become less physically affectionate than the child, that the adolescent may become less forthrightly communicative than the child – they are less likely to feel anxious, disappointed, or angry when these normal developmental changes occur.

4) Change creates ignorance.

Because change partly takes people from a known into an unknown experience, change creates continual ignorance and constant information needs, often causing worry when their need to know is denied. “What’s going on?”

This is why adolescence can be so emotionally taxing for young people. Too much change and too little control can create a lot of anxiety. For example, beset by the physical changes of puberty, waking up each day and confronting one's changing image in the mirror can be scary to do. What new blemish or bad hair problem will they have to put on public display at school today?

Not just physically, but emotionally, change is going on. "Why are you so touchy and edgy today?" parents ask. “I don’t know why!” replies the moody teenager, but within themselves, they may be wondering, “Maybe something’s wrong with me!” And now for them each, the young person can become more sensitive to live with than the child.

Parental ignorance often increases as child becomes teenager. They know more about the child’s world of experience (mostly within the family circle) than they do about the adolescent’s larger world of experience (more outside the family circle.) Further, the child is usually more forthcoming about what is going on (for closeness sake) than (for privacy’s sake) is the teenager. So what results is an information incompatibility: at an age when parents need to know more about the adolescent, she or he has a need to tell them less.

“Sometimes we feel like strangers in a strange land,” lamented a parent. “What are we to do?” “Keep communicating,” I replied, “to reduce the sense of strangeness you describe. Strangeness need not cause estrangement. Never be so busy or electronically preoccupied that you stop talking and listening, that you stop expressing interest and concern. Taking the time to exchange adequate information is the best antidote to growing ignorance and its discontents.”

5) Change causes conflict.

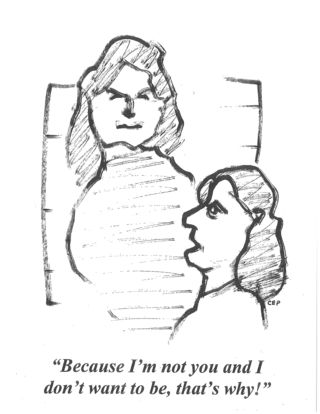

It’s not simply that change takes people from an old to a new set of living conditions; it creates a fundamental conflict of interests – between those invested in the old and familiar (like the parent) and those attracted to the new and exciting (like the adolescent.)

Generational interest and taste differences can also play a divisive role. Thus parents wed to the old popular music of their youth may discount or dismiss the new and unfamiliar popular music that their adolescent has bonded to. “How can you stand that noise?” There is always a contrast between the generations because of fashion and cultural changes. Part of differentiating from parents and becoming one’s own person, however, is the adolescent identifying with what feels uniquely her or his own. “You just don’t get what matters to me!”

Rather than treat normal generational differences as barriers to getting along by ignoring, discounting, criticizing, or warring over what feels unfamiliar, parents are better served by bridging these generational differences with interest, treating them as connectors and not dividers.

Rather than treat adolescent fascinations as misguided, treat her or him as an expert in something the parent is ignorant about but would like to be taught. “Can you help me understand what you love about that music; I would like to be able to appreciate it too.” “Would you show me how to play that computer game; I would like to learn to play.” Now the parent casts the teenager in the esteem-filling role of teacher and themselves as the ignorant student wanting instruction from a much younger person who knows more themselves.

In so many ways change is a challenge. Change begets change. Change incurs loss. Change violates expectations. Change creates ignorance. Change causes conflict.

To keep their footing during their child's coming of age passage, parents must learn to dance with adolescent change – partnering with their teenager through the many trials and transformations of growing up.

The steps are ruthlessly simple and endlessly complex, each step a decision they make. For example: parents must decide when to hold on and when to let go, when to lead and when to follow, when to bear down and when to back off, when to give space and when to provide company, when to shut up and when to speak up.

Important to remember is that the more things change for the adolescent, the more one thing needs to remain the same – the anchoring constancy of parental love.

Next week’s entry: Adolescent Questions about Teenage Apathy