Suicide

Professional Suicide

It’s jarring when accomplished people end their own lives.

Posted August 17, 2017

Sir Bernard Spilsbury was among the most famous of British pathologists during the early 1900s. He performed the autopsy in the sensational case of Hawley Harvey Crippen. In January 1910, Crippen’s wife Cora seemed to have disappeared. Crippen boarded a ship with his mistress but was arrested and returned to England. A female torso had been found in his house at 30 Hilldrop Crescent. The investigation turned up information that he’d ordered the toxic hydrobromide of hyoscin just before Cora disappeared. The torso tested positive for this substance. Spilsbury identified a scar on the torso’s lower abdomen as the result of a surgical procedure that Cora had endured. Crippen was convicted.

Spilsbury continued to gain prominence, especially for his meticulous work on the “Brides in the Bath” case in 1914. Margaret Lloyd had died in her bath, leading police to investigate her husband, George Joseph Smith. He’d married three times and each wife had drowned in the tub. Yet they bore no bruises and it seemed likely that they would have fought fiercely. This presented a mystery that Spilsbury wanted to solve. He set up an experiment using young women in bathing outfits who agreed to sit in bathtubs and allow him and a detective to try to drown them. The detective deduced that Smith had grabbed his wives by the ankles and pulled them quickly into the water, which rendered them helpless. The experiment showed this was possible and Smith was convicted.

Spilsbury acquired enormous clout and became a force in the courtroom. Yet, during and after World War II, he lost his sister, a mentor, and both of his sons; his marriage dissolved; and arthritis left him unable to meet his usual standards. He soon had difficulty paying his bills, while a stroke impaired his ability to think and to talk. Aware that he’d lost his edge and that younger men were replacing him, he decided to end his career on his own terms. On December 17, 1947, after sending his suicide note to a friend, he had dinner, went to his lab, and turned on the gas in his Bunsen burners. There he died at the age of 70.

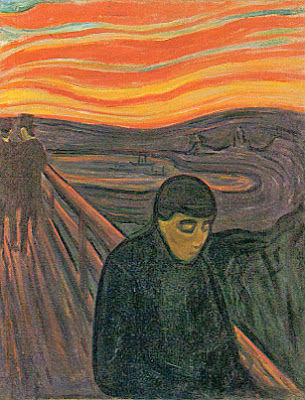

In moments of self-honesty, people like Spilsbury, who were once at the top of their game, can see the stark contrast between what they were and what they face. From a full life of professional accomplishments and personal achievement, Spilsbury had lost everything that had meaning to him. He received fewer cases and little acclaim. Even the closest of his colleagues was embarrassed for him. Some tried to protect him, but he saw for himself how it was all going to end. There was no possibility of recovering his faculties or his ability to perform. It would only get worse, creating a psychache too great to endure. Death with dignity while he was still able to do it seemed a better choice.

Surprisingly, physicians have a higher propensity to die by suicide than other people, usually from untreated depression.

Another British doctor who ended his life is famous for devising the first profile of a series of murders attributed to a serial killer — Jack the Ripper. In the autumn of 1888, Thomas Bond studied the evidence in four of the linked cases for two weeks and performed the postmortem examination of the fifth victim before delivering his theory. A registered police surgeon, Bond offered a description of the type of man whom he thought was responsible. The profile was detailed and comprehensive, but it did not help to catch the killer. (He also thought there were more than the official five victims.)

Bond assisted with other high-profile cases as well. As he aged, Bond suffered from gastrointestinal pain, insomnia, and severe depression. He turned to morphine, which proved ineffective. He was bedridden in his Westminster home for six weeks with unbearable pain and he threatened several times to kill himself. The nurses tried to be vigilant. Yet he spotted his opportunity early on June 6, 1901 when his nurse left him alone. Bond rose from his bed and threw himself out the third-floor window, falling 50 feet to the street below. He hit the pavement headfirst, cracking his skull open. He soon expired.

More puzzling is the suicide of Dr. Douglas M. Kelley on January 1, 1958, in his California home. He was just 45. He’d risen to prominence for the assessments he'd performed and analyzed of the top Nazi officers awaiting trial at Nuremberg. He'd also hosted a TV show called “The Criminal Mind.” His suicide was unexpected and abrupt, and some associates believed it was a code for dark secrets that involved military conspiracies.

As a U.S. Army psychiatrist, Kelley’s task was to evaluate the mental health of the incarcerated Nazi leaders. He spent a lot of time with Hermann Göring. In the hope of crystallizing the “Nazi personality,” Kelley used the Rorschach and the Thematic Apperception Tests, accepting the power of narrative devices to reveal hidden layers of the psyche. He found nothing that specifically set them apart, which disturbed him.

Back home, Kelley refused to allow his wife and three children to ask questions about his Nuremberg experiences, possibly because they upset him or possibly because (according to another source) the book he’d published, 22 Cells in Nuremberg, was propaganda written or dictated by someone else. Kelley became alcoholic and despondent. One day in his home, he took potassium cyanide, echoing Göring’s suicide method.

Yet there were no clear signals, aside from a history of dark moods and a few threats. Kelley had attended a party the evening before and appeared to others to be in good spirits. On New Year's Day in 1958, he'd picked up his father with plans to watch a Rose Bowl game. During the game, Kelley and his wife were in the kitchen preparing the meal. They got into one of their frequent fights. He ran up the steps and slammed the door. When he came down, he had the poison in his hand. He stood on the landing and threatened to swallow it. His wife, father, and eldest son begged him not to, but he tossed it down his throat. He died in the bathroom, foaming at the mouth. Having expressed admiration for Göring’s control over his own death, perhaps Kelley had decided he could bear no more professional and personal disappointments. He had left no note.

Whether or not such suicides are a surprise, they are certainly tragic endings to the lives of those who have accomplished and contributed so much.

References

Evans, C. (2006). The Father of Forensics. New York, NY: Berkley.

El-Hai, J. (2013). The Nazi and the psychiatrist. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

Andrew, L. B. Physician Suicide. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/806779-overview