I confess that I have never paid much attention to Howard Stern. Until now, when I happened on a CNN interview with Anderson Cooper. I’d dropped somewhere into the middle, where Stern is describing his childhood, his years of psychotherapy following a painful divorce, and how psychoanalysis changed his life.

Wait a minute. Psychoanalysis changed his life?

How many sexually obsessed, hyper-masculine guys talk like this? Isn’t he worried about losing his audience, his reputation for exposing his naked id? Think of his numerous interviews with “the Donald” in his playboy days, when both discussed how “hot” Melania was, not to mention other Trumpian adventures. I grant you that Stern did not highlight his own sexual escapades, even referring at times to the small size of his penis, but he had a gift for tapping into the unbridled libido of his guests.

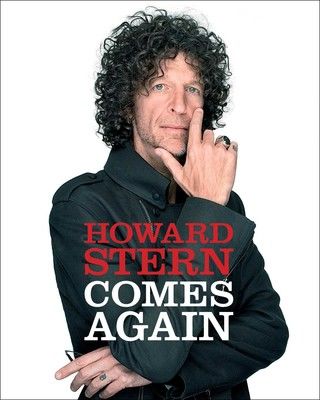

What happened between his previous books Miss America (1995) and Private Parts (1993)—which he has disavowed and suggests that you burn—and his recent release Howard Stern Comes Again (2019)? He began, he says, to reflect on his life and how he relates to others. Here are some excerpts from his recent NPR conversation with Terry Gross.

Commenting on the change in Stern’s interview style, Gross observes: “You go deeper….You have more empathy.” Stern credits his twenty-year-long experience of psychotherapy, including classical analysis, which he claims “did a big change for me…I went there, because, you know, I wanted to examine my relationships, how I related to the world and the people around me.”

At first, he didn’t know how to talk about himself. When he presented a comic routine about his life at his first therapy session, his analyst responded simply: “I don’t find any of this funny….I find it rather sad.” Stern realizes that he has been “listened to” in a real way—perhaps for the first time. From this experience, he deduces that he has been conducting competitive monologues with his radio guests, rather than attending to what they have to say. This might be enough revelation for a rock-star radio host, but Stern goes further.

“It’s a strange thing,” he reflects, “what happens with trauma when you are young. You shut down if you want to self-protect…My feelings and difficulties were not on the table. And so I buried them.”

My ears began to prick up.

Trauma theory posits a shutting down of emotion (and sometimes memory) in the face of overwhelming experience. Think sexual abuse, think war veterans with PTSD, think the Holocaust. When experience is too sudden, shocking, baffling, or simply indigestible, we tend to exclude it—by pretending it didn’t happen or just not responding. Gross continues. “What specifically,” she asks, “is the trauma of your early years?” “Well,” Stern replies, I think it was the burying of emotion…It was certainly being in a lot of fights.”

Towards the end of Part I of this amazing interview, Stern returns to the subject of psychotherapy. In a remarkable series of admissions, he says “I began a process of really becoming empathic with people and empathic with my daughters [from his first marriage] and with my wife.” He concludes “I’d never been given lessons on how to be a man.”

Enter Carol Gilligan.

Carol Gilligan has spent her career studying the ways that girls and boys form their identities in a highly gendered and polarized society such as ours. She is justly famous for her many publications on this subject, beginning with In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development (1982).

Recently, she has linked her observations about how girls lose their assertiveness in adolescence while boys suppress their capacity to express emotion to theories of early childhood development and the tenets of trauma theory (Why Does Patriarchy Persist? 2018).

She and her co-author Naomi Snider maintain that children whose emotional needs are not met in their early years tend to “shut down,” in an effort to survive. In a patriarchal society, they maintain, girls struggle to speak their own minds in an effort to preserve their “likability,” while boys are encouraged not to show emotion in order to develop the manly trait of self-sufficiency. Girls don’t speak up for themselves, and boys don’t cry.

Stern says something similar about himself. He grew up in a household where his parents did not encourage the expression of feeling. His father, a radio engineer, whom he describes as unemotional, introduced him to the intricacies of his profession but did not confide in him. Following the manly code of silence, his father kept his thoughts and feelings to himself.

Stern’s mother had a traumatic history of loss. Her mother died when she was nine years old, and she was sent to live with a distant relative in the Midwest, not even being informed of her mother’s death. This loss haunted her, leading to years of depression, in which she sometimes threatened to kill herself. Stern, as a child, tried to comfort her without knowing what was wrong. Any child in this circumstance, Stern comes to understand through therapy, will defer his own emotional needs in the face of a parent’s distress.

Stern seems to exemplify Gilligan’s argument about masculine development in patriarchy. Lose your emotions and learn to act “like a man.” In the aftermath of his divorce, Stern realized that this formula no longer worked for him. Instead, he began to explore what it was like to be the child of traumatized parents who could not attend to his emotional needs. Having explored this hitherto closed-off area of his own life, he is now sensitive to the hidden stories and vulnerabilities of his guests. As a result, he has adopted a strategy of what I would call “radical listening” in his interviews.

This is hardly the path that his one-time interview buddy Donald Trump (who asked Stern to endorse his nomination for President) has followed. When queried by David Marchese in a New York Times interview (May 9, 2019) about whether he thought President Trump is “capable of a certain level of soulful introspection,” Stern replied simply “No, I don’t.”

Pursuing this question he says “’Donald is a well-guarded personality. I think that he’s so emotional that somewhere along the line he had to close it off….Donald has been traumatized.” Traumatized people, he reflects, “learn how to turn off what you’re calling a soul. It’s not that they don’t have one. It’s that the pain of emotion is so intense they turn it off.”

Gilligan, I believe, would agree. She sees the gendered norms of our society as taking a toll on both girls and boys, men and women. She attributes these norms to patriarchy, and she considers patriarchy itself as traumatic insofar as it involves the shutting down of emotion in boys and the loss of self-assertion (hence access to their true thoughts and feelings) in girls.

Stern validates what Gilligan has to say about the tender vulnerability of boys and the choices they face in suppressing this aspect of their selfhood. Given the option, I think he’d now choose Gilligan over Trump as an interview subject.