Depression

Holiday Heartache

Finding hope in the holidays after loss.

Posted September 12, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Growing up, Jesus’ birthday meant an 11-foot Fraser fir, cards strung from wall to wall, and waking up at 5 a.m. begging Ma to let me open just one present before Daddy woke up. You could barely glimpse the tree beneath layers of baubles, lights, tinsel, and presents, but its scent permeated every crevice of our house. Magic. Even my father’s ranting over tangled lights and prickly pine needles didn’t dampen the holiday spirit.

On Christmas Eve, my mother and her sisters cooked all day to serve dozens of relatives a cornucopia of delights including turkey, ham and pork. Our traditions expanded with the next generation. Guest appearances from Santa halted, however, when my 3-year-old nephew Joseph stared suspiciously at Mr. Claus’ feet and said, “Santa’s wearing Grandpa’s shoes.”

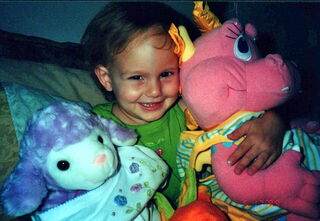

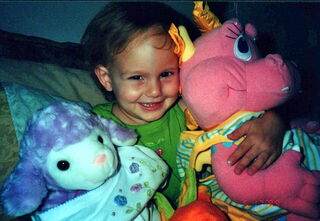

When my daughter Jillian came along, I expected her to experience the same wonder of the season as I had (minus the cursing). On her first Christmas, a haven of relatives cradled her, passing her from one to the other, aahing and oohing, each vying for the scent of baby. She was 14 months when her second Christmas rolled around, shoulder deep in crinkled wrapping paper, filled with the glee only a toddler could muster.

Then the unthinkable happened. At 23 months, Jillian was diagnosed with neuroblastoma, an aggressive solid tumor. The next two Christmases fell in the shadows of chemotherapy, surgeries, two stem cell transplants, and radiation. But I didn’t know how challenging Christmas could become until Jillian died, when grieving became my full-time job. I tried everything from therapy, to hellish supports groups and real support groups; from prayer, yoga, and meditation, to reading, writing, and drawing; from vacationing, to crying in my husband Tom’s arms, only to find fleeting relief, or none at all. The pain kept returning with a vengeance, like a rampant wildfire raging inside my heart.

Being a psychologist, I knew grief could not be bypassed. I had to walk through it to move beyond it. So I set up an anger management room. Item by item, I threw all of her medication and medical supplies in the guest shower, screaming and cursing. Stomping, smashing, and ripping, it didn’t make sense that I was alive and my daughter was dead. I wanted to die.

Instead of killing myself, I decided to do something normal. But going to the mall at Christmas was perhaps the dumbest idea I tried. When I reached Citrus Park Mall, I couldn’t use the spot for “stroller customers only” anymore. I parked in a regular space and walked the extra 50 feet, where the familiar sights, sounds, and aromas overwhelmed me. Feeling dizzy, I plodded through the holiday decorations. Jillian would have been 4, an age where the magic of Christmas is most alive. What was I thinking?

As I trudged alone in the surreal environment, I saw the Disney Store on the right, a favorite old haunt, but that day Mickey mocked me and dared me to go inside. The memories disoriented me like paparazzi flashes.

Walking past Gymboree, a suffocating pain gripped my chest. Too many memories of Jillian; hiding under the clothes racks; pointing at dresses saying, “That’s cute.” No way I could ever shop for girls’ clothing again.

To the left, the bronze boy statue with outstretched arms missed the petite blonde girl with the silly giggle, hanging from him, and swinging back and forth, back and forth, saying, “Look at me, Mama!”

Seeing all the people with their children who didn’t yet realize the world could turn upside-down at any moment, I had to leave—fast!

Doing something “normal” was not the answer.

Later that day Tom and I went to a support center where a burly, imposing minister spoke about holiday coping strategies. “Do something new. Doing the same thing magnifies the loss. We all heal differently,” he continued. He tried to understand, but he didn’t have a clue about this unyielding pain that clings to your soul for dear life.

To my left sat a blonde woman around my age, who had lost her 7-year-old son to neuroblastoma a few years earlier. She articulated my reality. “The first year is awful. You’re in a pit and you can’t see the light above. Next to the pit lies a deep abyss. No one wants to go down there, but every time you do, you feel a little lighter when you come out. You can only sink into the abyss for short periods because it is painful beyond belief.” She understood my experience because it was hers, too. Most of us know the pain of the pit because we’ve been there a time or two, but the abyss is reserved for those who have survived extreme losses. The pain of the abyss is indescribable. Maybe I wasn’t losing my mind. Maybe it was a normal reaction to incomprehensible loss.

As the session ended, Tom snarled at me for dragging him there, but I had renewed hope. Tom grieved in brief, intense bursts, while I grieved almost continuously. He claimed to heal through video game therapy. “We all heal differently,” the minister had said. “Do something new.” Maybe he was right.

A “Charlie Brown Christmas tree,” the kind without pine needles, would help me through the holidays, I decided.

Later in the week, Tom and I bought a 3-foot potted plant at Home Depot that vaguely resembled a Christmas tree. My nephew Frankie agreed to help me decorate it. Tom and I pulled boxes of Christmas decorations from the attic and stacked them in the living room.

Frankie hobbled in and said, “Me-er-ry Chri-i-stmas,” borrowing the voice of a 90-year-old depressed woman. Before I could respond, he charged into my bedroom, selected some Christmas CDs and blasted them so everyone within a two-mile radius could hear. He opened the blinds in the foyer and asked, “Where’s the tree?”

“Right in front of you.” I pointed to the houseplant on the floor.

“Maybe we should close the blinds this year,” he laughed at the sad houseplant and mimicked drawing the blinds. “No, really, it’s a lovely idea. Let’s put it near the front window so the whole neighborhood can admire it.” He snickered as he lifted the plant.

“Not our usual 11-foot Fraser Fir, is it?” We giggled, trying to disguise the sadness in our hearts. It’s not unusual for Frankie to make me laugh even in the grimmest situations.

Tom shuffled past us toward the bedroom, rolling his eyes at our giddiness. He turned off the Christmas music and switched on the television.

Frankie pulled out fabrics and ribbons to create something resembling an altar and reverently set the plant on it. Tears alternated with laughter as we hung dozens of pictures of Jillian on the tree using silver snowflake clips. Each memory, each photo almost brought Jillian home for Christmas. I gazed at a picture of her third Christmas; a feeding tube attached to her nose, bandages on her cheek support it in place. I remembered taking a roll of pictures of her wearing that black and white checked dress and hat. Recently diagnosed, that was the worst Christmas ever, until now.

I imagined Christmas with Jillian alive. Tom and I would have awakened to the awe and wonder of a 4-year-old discovering Santa brought all she wanted.

Frankie interrupted my daydream. “Maybe we should sprinkle the tree with Jillian’s ashes for a real special snowflake look.”

“Not funny.” I scowled.

Disregarding my response, Frankie reached into a box of Christmas decorations and pulled out a miniature angel with a white gown my aunt had crafted years before. As he lifted the angel, her hair fell out in one big clump, just like Jillian’s had. We stared at each other. Tears spilled from my eyes as we burst into hysterical laughter. In between the sidesplitting gasps, Frankie looked up with the angel in hand and said, “Hi, Jillian.”

“She reminds me of Jillian after chemotherapy,” I said, stating the obvious. We both felt Jillian’s strong presence, helping us through the holidays.

“How about some bows?” Frankie pulled a spool of blue ribbon from the box. We decorated the plant entirely with bows, pictures of Jillian, and a few angels. When we were done, we both took a few steps back and admired our work.

Tom emerged from the bedroom, saw our tree and joked, “It’s small, bald, and beautiful! Just like Jilly-boo. I like it.”

I moved closer to Tom and he put his arm around my shoulder. As I gazed at the tree, I knew it would help us through the holidays. Like a reflection of us, it was sad and pathetic, yet full of beautiful memories of Jillian.

The minister’s words held true, everyone heals differently and must try something new. Besides the Charlie Brown Christmas tree, new for me meant writing, for Tom it was drag racing. Over the years, I’ve heard many others heal in this way. When the novelist Ann Hood’s daughter Grace died, learning to knit eventually carried her out of despair. It’s as if you must create a new chamber in your heart to keep it beating, despite the gaping hole.

Ten years later, Tom and I are far from the abyss, and Christmas is almost Christmas again.

Reprinted from Reader'sDigest.com.