Friends

Why Was Mask Wearing Popular In Asia Even Before Covid-19?

Find out which masks are most popular in Asia and why.

Posted May 17, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

By the time the city of Wuhan in Hubei Province, China, was placed on lockdown on January 23rd, pictures were flooding the western media of Chinese citizens wearing medical masks during the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak. The photos reminded me of the ones coming out of China in 2002-03 during the SARS outbreak, which infected roughly 8,000 people and killed almost 800 before it was successfully contained. Given that 87 percent of reported SARS cases and 84 percent of deaths were in China and Hong Kong, like most Americans, I wasn’t worried about my safety or that of my friends and family during the SARS epidemic. There were only eight cases diagnosed in the United States, so I never considered wearing a mask, nor did I know that the practice would become more entrenched in Asia after the contagion had been quelled. It was already customary for Asians to wear a mask to protect others when they were sick, so wearing a mask was a given for them during the recent Covid-19 outbreak.

But our current situation is incontrovertibly different. Since the WHO declared COVID-19 to be a “global public health emergency” on January 30th, the potentially deadly coronavirus has spread rapidly throughout the world. In an attempt to save lives and prevent the collapse of healthcare systems, the leaders of most countries have placed their people under some form of lockdown or shelter-in-place order.

In the first chaotic weeks and months of the pandemic, Americans were discouraged from wearing masks, but the overwhelming preventative benefits to wearing them eventually overrode the naysayers. Since early April, the U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams, the CDC, the WHO, and multiple other medical groups have been recommending that everyone wear them–even when socially distancing. In many U.S. states and European countries, masks are now required. In Austria, you can’t go into a grocery store without wearing one. It’s the law.

-----

We now know that COVID-19 is transmitted by ingestion–through the eyes, nose, or mouth–of droplets emitted when infected people sneeze, cough, sing, shout, or even talk. We also know that many people who test positive are asymptomatic and that the virus seems to be the most contagious in the days before and right after a person develops symptoms. So when an infected person wears a mask, they are protecting others by blocking their contagions from escaping. As early as March, an article in the journal The Lancet recommended that people wear masks to prevent COVID-19 from being transmitted by asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic carriers.

Multiple studies have shown that surgical masks (the ones most commonly worn on the streets in Asia) can also protect wearers from some of the virus’s particles, although what percentage depends upon the type of surgical mask. (Those with a water repellent layer are more effective.) N-95 masks protect wearers from most of the virus’s particles (up to 96 percent in some studies) as long as the mask is fitted correctly. Multiple studies have also found that wearing any mask, including a homemade one, protects the wearer from COVID-19 to a larger degree than wearing no mask at all. The University of Edinburgh tested common masks and found that some surgical masks protected the wearer against 80 percent of particles as small as .007 microns. (That’s ten times smaller than the average COVID-19 particle.)*

Yet here in the U.S., some people refuse, even violently at times, to comply. Why is this? Is it because they think that historically we’ve never worn them? Maybe they don’t know that mask-wearing was widespread in the U.S. during the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918-19 that killed roughly 675,000 Americans and over 50 million worldwide.

Is it because masks can be a bit uncomfortable to wear? Surely it’s more painful to get a tattoo, or pierce our body parts, or wear stilettos? Countless Americans endure very real pain for the sake of sporting these styles. Doesn’t this prove that we can do something uncomfortable if we set our minds to it–especially for something as important as protecting ourselves and others during a pandemic that is spread through respiratory drops? (And what could be more “uncomfortable” that dying of COVID-19 or losing a loved one to this disease?)

Is it because we’re American and no one’s going to tell us what to do–even if it means endangering others, ourselves, our family, and our country’s economy–since spreading the virus just means we risk staying closed down longer or even having to close down again, once we start to open up? Surely we are better than that.

If it’s because we associate mask-wearing with being ill, as some journalists have speculated, maybe we should start a new fad. In Asia, it’s considered good hygiene to wear a mask. It’s thought to be considerate of others. It can even be stylish to wear a patterned mask. Maybe we should think of donning our masks as a way to honor our health care workers and first responders, much the same as we display red hearts to show our support for them in many parts of the U.S.

-----

When I first lived in Tokyo in 1984, I noticed that people sometimes wore medical masks out on the street. When I asked the other ex-pats, they told me that the Japanese wore them when they were sick, to protect others from getting their germs. Being uber polite and group-minded people, this made sense to me. They felt it was their civic duty to protect others.

Being an American, it never occurred to me to wear a mask when I lived in Tokyo, even the few times I had a cold. I just stayed home. It seemed too foreign, too uncomfortable to wear a mask. It would have been like wearing kimono, the elegant traditional dress–with its many under-layers, heavy silk obi tied at the waist in a cumbersome knot, the heavy silk outer robe, and torturous-looking footwear called geta. (Well, maybe wearing a mask was not quite as uncomfortable as wearing kimono, but it wasn’t something I wanted to do.)

Fast forward to 2010 when I lived in Tokyo again. Right away, I noticed that medical masks had become ubiquitous. And when I traveled to other countries in Asia, such as South Korea, China, Thailand, and Malaysia, it seemed that many more people were wearing them than decades before. When I asked, I was again told that people wore them when they were sick, to protect others. One was expected to wear them, and it was considered extremely selfish not to. People also wore them to protect themselves from air pollution, especially in China. After the SARS epidemic in 2002-03, it became commonplace to wear masks to protect oneself from germs, not just to protect others. By 2010, mask-wearing had become extremely common, even stylish, in Asia.

When we moved to Beijing in 2011, there were days when the pollution was so thick that I couldn’t see more than four feet outside our windows. It seemed foolhardy to go outside. On those days, I stayed in our air-filtered apartment and worked on my computer. My husband shuttled by car from our apartment to his air-filtered office. Even when I finally broke down and bought us masks, I couldn’t bring myself to wear one. I felt strange, like a bandit in the Wild West, an American cowgirl gone bad. Instead, I waited until the pollution had cleared to go out. Even when my husband had to brave the thick smog to go to the office, he refused to wear his mask. “I’m just walking from the building to the waiting car. I don’t need it,” he insisted.

-----

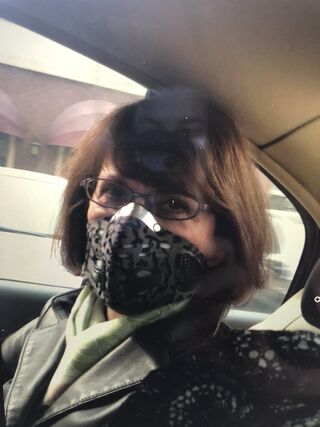

Now that we’re in the middle of a worldwide pandemic, I’ve learned to wear a mask. (My husband has too.) I don’t love it. It’s not particularly comfortable. I feel weird. I have a bit of trouble breathing. But I do it anyway. I do it to protect others. I do it to protect my family and myself. I do it because all the countries that have had success in slowing the spread of this terrible disease have insisted their citizens wear masks. I do it to thank all of our health care workers and first responders for their selflessness. I do it because it’s my duty as an American to help my country slow this epidemic. I view it as the patriotic thing to do. I hope you do too. **

References

*Study cited in Smart Air

**Article Sources: NIH and CDC websites, CNN, Nature, South China Morning Post