Defense Mechanisms

The Origins of Writer's Cramp

Is focal dystonia the whole answer?

Posted March 30, 2022 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- There is more than one type of writer's cramp.

- Keyboard operators, musicians, and professional sports people can develop similar occupational cramps.

- Writer's cramp may be the first symptom of an adult-onset dystonia.

- Extensor forearm compartment syndrome may be a cause for pain on writing in some people who are diagnosed with repetitive strain injury.

In a supplement to the 1713 edition of his book De Morbis Artificum Diatribo, Bernadino Ramazzini discussed the afflictions of notaries and scribes:

“An acquaintance of mine, a notary by profession, still living, used to spend his whole life continually engaged in writing, and he made a good deal of money from it; first he began to complain of intense fatigue in the whole arm, but no remedy could relieve this, and finally the whole right arm became completely paralyzed. In order to offset this infirmity, he began to train himself to write with the left hand, but it was not very long before it too was attacked by the same malady.”

Constant writing under mental stress, Ramazzini believed, could lead to fatigue and discomfort in the hand muscles in susceptible individuals; he recommended its treatment with salves. In the 19th century, the incidence of writer’s cramp increased as a result of the burgeoning number of clerks required to produce copper plate calligraphy with a metal nib rather than a quill, as well as the move for mass education. The most proficient Morse code operators made more than 500 muscular contractions a minute, twice as many as any typist, and the "epidemics" of telegraphist's cramps between 1850 and 1920 raised the possibility that continuous overuse of hand muscles might be a causative factor for all occupational hand cramps

Physicians with a special interest in neuromuscular disorders saw large numbers of cases of writer’s cramps and came to tentative conclusions about the mechanisms responsible for the disability. French neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne, Jean-Martin Charcot’s mentor in Paris, identified two distinct varieties, the first due to a local overuse of muscles and a second form, which he believed to have a nervous origin. George Vivian Poore, a physician at University College Hospital, London, considered peripheral repetitive muscular strain in the forearm and hand muscles to be important in many cases, while his colleague, William Gowers, believed that faulty penmanship resulted in a derangement of a center for writing located somewhere in the cerebral cortex. The curling of a child’s leg around the chair when learning to write at school and the persistence into adult life of a slight tongue protrusion while writing testified to the delicate motor skills required in the act of writing. Gowers suspected that a regression along the developmental path upon which the complex motor skill was originally learned occurred. Joseph Babinski later suggested that writer’s cramp might arise in the corpus striatum.

Despite these early observations based on the study of large numbers of cases, for much of the 20th century, writer’s cramp was considered to be psychoneurosis related to hysteria. In 1983, the neurologists David Marsden and Michael Sheehy published an influential article based on personal study of 29 patients with writer’s cramp. Some of the cases they studied exhibited abnormal postures of the fingers and wrist that closely resembled the hand cramps seen in inherited adult-onset dystonia, and a few also had a slight tremor when writing. They also noted that in rare instances, writer’s cramp could be the first symptom of Parkinson’s disease. They concluded their paper with the following observations relating to possible causation:

“There must exist within the brain some mechanism for storage, retrieval and execution of the motor programme responsible for an individual's characteristic script. The form in which we sign our name or write is instantly recognizable but is independent of the muscles involved. Our signature is the same whether we execute it in the usual fashion with hand and forearm muscles, or by writing with chalk or a felt tip pen on a blackboard with proximal shoulder muscles; the same signature appears whether we write normally or upside down, or even in the absence of gravity. All this must indicate that the motor programme responsible for our script can operate whatever the circumstances, by using which ever muscles are required. We sign our name with the eyes shut and even with an anaesthetic hand (the fingers being bandaged to the pen). The brain must contain a mechanism capable of generating the engram of our script independent of which muscles are required, and of sensory feedback, so we would look to some breakdown of this mechanism to explain writers' cramp.”

Marsden and Sheehy’s viewpoint that writer’s cramp and other occupational cramps were focal task-specific dystonias led to new referral routes and treatment approaches. Forty years on, keyboard operators are now more commonly seen, but occasional cases of writer’s cramp still occur in young adults, including students where transcription of lectures and writing under time pressure in examinations are required.

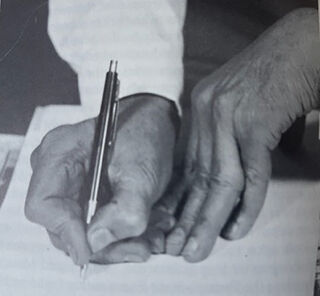

It usually begins gradually with tightness in the fingers after prolonged periods of writing. The pen is gripped too tightly, creating a drawing sensation and causing it to be driven through the paper. Sometimes the finger slips off the pen, or an involuntary lifting of the thumb or index finger is seen. A dull ache develops in the back of the hand, and fluency and alacrity of writing diminish. As the condition worsens, it may become impossible to even pick up the pen or start to write. The muscles involved in gripping the pen often seem to be more affected than those used to move the pen across the page. The thumb and the first finger are flexed at the first proximal interphalangeal joint, and the hand is extended at the distal interphalangeal joints.

Sometimes there is also the isolated extension of a finger. The wrist may be flexed, extended, or supinated, and sometimes the whole arm feels tense and in spasm. In severe cases, discomfort occurs after writing only a few letters, forcing the sufferer to take the pen temporarily off the page and shake the hand. Holding the pen between the extended middle and index fingers and supporting the writing hand with the other hand or even the top of the pen with the chin are compensatory strategies used by some patients. Occasionally writer’s cramp seems to follow soon after an injury to the hand.

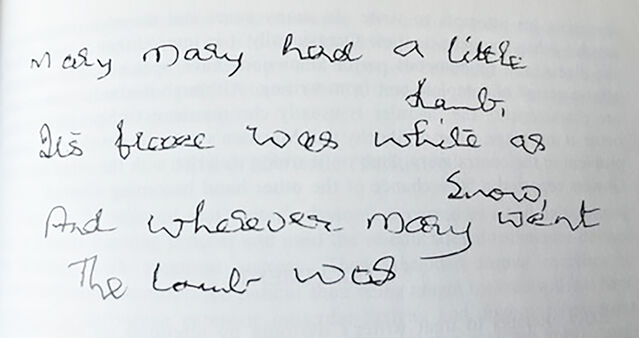

Although the script has no distinctive features, the handwriting is usually untidy, jerky, and infantile and changes in size (may get smaller or larger). Some of the downstrokes appear thickened, and sometimes a tremulousness can be observed

. Free writing in mid-air or writing on a blackboard is unaffected. Reduced arm swing when walking and a mild increase in tone are sometimes found on neurological examination.

Using a felt-tipped pen or a fountain pen with a bulbous shaft or putting the pen through the middle of a potato may be of help. The use of more sophisticated writing devices under the expert supervision of an occupational therapist may also be beneficial. Switching writing hands can also sometimes help, but the problem commonly recurs in the non-dominant hand. Targeted botulinum injections by weakening abnormally over contracting muscles can also improve writing, but full functional recovery or even complete remission is very rare.

Although most neurologists believe that writer’s cramp is a focal dystonia which in some instances can extend to interfere with other dextrous activities and slowly spread to involve other body segments, there are many individuals referred because of writing or typing difficulties whose symptoms differ from those described with dystonia and more closely resemble some of the descriptions of telegraphists cramp and scrivener’s palsy from over a hundred years ago. These individuals complain of severe, aching fatigue and burning discomfort in the forearm on writing or typing, sometimes associated with feelings of coldness in the affected hand or pins and needles in the fingers. Rheumatologists ofen label them as repetitive strain injury or diffuse arm pain. In these individuals prolonged activity of the hands as occurs in writing can lead to local compression of muscles in the forearm extensor compartment leading to ischemia, with swelling a syndrome analogous to the anterior tibial compartment syndrome (shin splints) seen in long-distance runners and footballers. In this second type of writer’s cramp, surgical decompression of the extensor compartment has shown early promising results.

There are also some people who become fixated on their difficulty in writing even though they do not need to write in their jobs, and who despite reassurance become desperate to find a solution. Behavioural therapy and medical hypnosis may be worth trying but some of these individuals remain anxious and worred that the problem will spread to involve other tasks.

References

M. P. Sheehy and C. D. Marsden. Writers' cramp-a focal dystonia. Brain 1982 Vol. 105 (Pt 3) Pages 461-80

M. H. Pritchard, R. L. Williams and J. P. Heath. Chronic compartment syndrome, an important cause of work-related upper limb disorder Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005 Vol. 44 Issue 11 Pages 1442-6