Sport and Competition

The Psychology of Competition

How competitions can lead you to do the right thing for the wrong reason

Posted June 24, 2015 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Competitions are fun, let’s be honest. At one point or another in your life, you probably have enjoyed being part of some kind of competition. Of course, competitions tend to be more fun if you actually win. Competitions have the undesirable quality of being a “zero-sum” game (i.e., in order for you to win, someone else must lose). Nonetheless, throughout human history, people seemed to have enjoyed organizing competitions in one form or another, from the ancient Greek Olympic Games (going back as far as 776 BC) to modern soccer (I would say American Football, but soccer is actually the most popular sport in the world). In fact, when you look closely, you’ll notice that competition is everywhere in modern society. Economists tell us that competition is an essential force in maintaining productive and efficient markets (i.e., without basic competition between firms, evil monopolies will form). Competition also plays a major role in domestic politics (e.g., presidential elections), foreign relations (e.g., states compete for power and resources), most sports of course, and even the human quest for love is not free of competition. For most people, there is something inexplicably compelling about the nature of competition. Perhaps that’s because, as some scholars argue, “competitiveness” is a biological trait that co-evolved with the basic need for (human) survival.

Given the seemingly powerful role of competition in human society, we might ask whether it is possible to leverage competitions for pro-social causes as well, such as getting people to donate to important charities or save energy to help the environment?

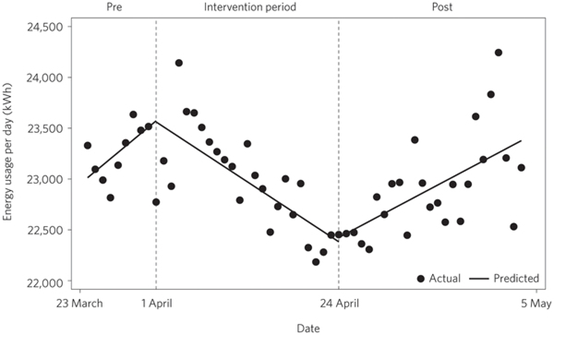

In a recent study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, I try to answer this question. As an example, I analyze the behavioral impact of a popular energy conservation competition that is administered yearly at Princeton University (the “Do-it-in-the-Dark” campaign). During the competition period, students across all residential colleges compete to conserve energy and the college that is able to conserve most energy by the end of the competition period wins and usually receives a prize of some sort (e.g., a paid study-break). I have plotted the results below (daily energy consumption across all residential colleges on the vertical axis and time on the horizontal axis). If you look at the behavioral pattern, you’ll quickly notice something very peculiar: once the competition starts it seems to have a remarkably positive impact on energy consumption (i.e., people are using less energy; usage steeply slopes down). Yet, here is the kicker: as soon as the competition ends, the trend is reversed and energy consumption bounces right back up to the point at which it started before the competition was launched! This sort of competition is not unique to Princeton, there are well over a hundred universities that yearly take part in the so-called “campus conservation nationals."

A “competition," by its very nature, is what psychologists call an “extrinsic incentive." Extrinsic simply means that the motivation to adopt a behavior or decision is sourced externally rather than internally (e.g., when you do something because you get a reward for it). A fundamental characteristic (and downside) of nearly all extrinsic incentives is that they only tend to work for as long as the incentive is maintained! In our example, students stopped saving energy as soon as the competition ended.

The opposite of extrinsic is what we call “intrinsic” motivation. When we are intrinsically motivated to do something (e.g., helping others, save energy) we do it not because of an external reward, but simply because we are personally convinced that it is the right thing to do. By “right” I don’t refer to vague cultural conceptions of good and evil, but rather to morality as an evolved capacity. Long-standing research has shown that the ability to be compassionate, empathize with others and to care about the natural world are evolutionarily adaptive behavioral traits. In fact, a psychological concept known as the “helper’s high” suggests that “doing good” actually makes people “feel good” both psychologically as well as physically (helping behavior often releases “feel-good” neurotransmitters such as oxytocin, a process which economists refer to as “warm-glow”). For example, an interesting recent study showed that people’s body temperature goes up when they are acting “green” (a literal warm-glow!).

Unfortunately, lots of psychological research has also shown that external incentives “crowd out” (i.e., undermine) people’s intrinsic motivation to do good. For example, highlighting the monetary benefits of saving energy actually makes people less likely to do so. This is related to what we call negative “goal-replacement.” Consider that if you were originally intending to save energy because you strongly care about the environment but instead, now simply do so to win a competition, your pro-social motivation for caring about the environment has been “replaced” with a self-serving goal (i.e., winning). Think about other goals such as quitting smoking or losing weight. Are you more likely to achieve either of these goals as a result of a temporary competition or because you are internally convinced that it is the right thing to do? You might ask what the difference is if they both have the same outcome. There is a difference. Let's say that you do end up saving energy (temporarily) because it helps you lower your monthly bills. Will you still save energy when your income suddenly goes up?

I am not suggesting that fun challenges or competitions are not useful for raising awareness and achieving short-term goals. For example, take the ALS ice bucket challenge that went viral last year on social media: the campaign ended up raising millions of dollars (which is good). Yet, do we honestly expect that by pouring a bucket of ice over our heads people have come to care deeply about ALS as a cause? Of course not. Yet, this is important because, although sometimes a challenging competition can be a useful mechanism to achieve one-off, short-term pro-social goals, many urgent societal problems, from social inequality and poverty to global climate change, require long-term motivators of positive behavior change. Psychological research suggests that intrinsically-motivated behavior change is much more likely to be sustained in the long-term.

Let’s not forget that competition is not the only dominant force in nature, it is rivaled only by its better half: cooperation. Indeed, humans not only survived by competing but perhaps more importantly, we survived by cooperating with one another. In the words of Bertrand Russell, “the only thing that will redeem mankind is cooperation."

It's time we start doing the right thing, for the right reasons.

References

Christiansen, F.B., & Loeschcke, V. (1990). Evolution and competition. In K. Wohrmann & S.K. Jain (Eds.). Population Biology (pp. 367-394).

Deci, E.L., Koestner, R. & Ryan, R.M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627-668.

E.O. Wilson (1987). Biophilia. Harvard University Press. Boston, MA.

de Waal, F.B.M. (2008). Putting the Altruism Back into Altruism: The Evolution of Empathy. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 279-300.

Post, S. (2005). Altruism, happiness, and health: it's good to be good. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12(2), 66-77.

Schwartz et al.(2015). Advertising energy savings programs: The potential environmental cost of emphasizing monetary savings.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 21(2), 158-166.

Taufik, D., Bolderdijk, J.W., & Steg, L. (2015). Acting green elicits a literal warm-glow. Nature Climate Change 5(1), 37-40.

van der Linden, S. (2015). Intrinsic motivation and pro-environmental behaviour. Nature Climate Change, 5(7), 612-613.

van der Linden, S. (2011). The Helper's High: Why it feels so good to give. Ode Magazine, 8, 26-27.