Education

Why Do Rich Kids Have Higher Standardized Test Scores?

Academic achievement, family income, and brain anatomy are interconnected.

Posted April 18, 2015

Why do children from lower-income families tend to lag behind students from wealthier homes on standardized test scores and other traditional measures of academic success?

On Apr 17, 2015 researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University reported that the academic “achievement gap” between lower-income and higher-income children is reflected in brain anatomy.

This study did not explore the potential causes for these differences in brain anatomy. However, previous research has shown that lower-income students tend to: suffer from more stress in early childhood, have more limited access to enriching educational resources, and receive less exposure to spoken language and vocabulary early in life. When all of these factors coelesce, they can lead to changes in brain structure, cognitive skills, and lower academic achievement.

What Can We Do About the Ever-Widening Achievement Gap?

Unfortunately, in recent years, the achievement gap in the United States between high- and low-income students has widened. According to Martin West, an associate professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and an author of this study, even though the gaps along lines of race and ethnicity have narrowed—the income achievement gap continutes to widen.

"The gap in student achievement, as measured by test scores between low-income and high-income students, is a pervasive and longstanding phenomenon in American education, and indeed in education systems around the world," West said in a press release. Adding, "There's a lot of interest among educators and policymakers in trying to understand the sources of those achievement gaps, but even more interest in possible strategies to address them."

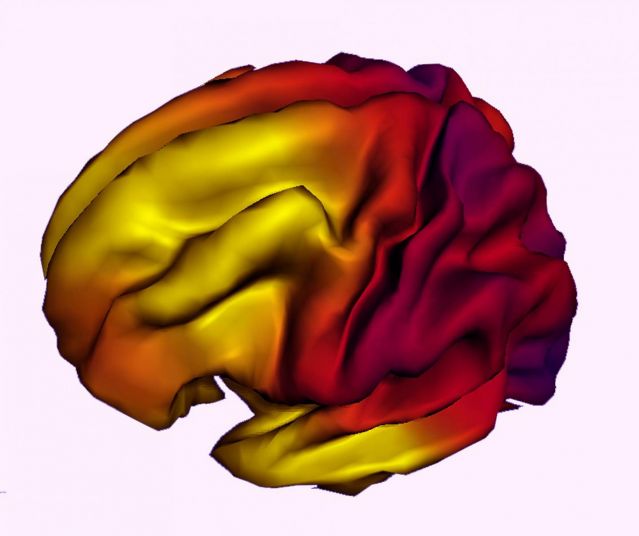

For this study, the researchers compared MRI brain imaging scans of high- and low-income students. The researchers found that the higher-income students had thicker brain cortex in areas associated with visual perception and knowledge accumulation.

The researchers found differences in the thickness of parts of the cortex both in the temporal and occipital lobes. The primary role of these regions are in vision and storing knowledge. The differences in cortical thickness correlated directly with differences in both test scores and family income.

These differences in brain structure were also correlated with one measure of academic achievement—which was higher scores on standardized tests by the students from higher income families.

The Harvard and MIT researchers estimate that the differences in cortical thickness of these brain regions could account for as much as 44 percent of the income achievement gap found in this study.

Previous studies have also shown brain anatomy differences associated with income, but did not link those differences to academic achievement. These findings corroborate similar findings released last month by a team of investigators from nine different universities who identified a correlative link between family income and a child’s brain structure.

Last month, I wrote a Psychology Today blog post titled, “Socioeconomic Factors Impact Childhood Brain Development,” about the March 2015 study, “Family Income, Parental Education and Brain Structure in Children and Adolescents,” which was published in the online edition of the journal Nature Neuroscience.

In the largest study of its kind, the team of investigators identified a correlative link between family income and a child’s brain structure. The correlation between brain structure differences and family income were the most dramatic in lower-income families.

This blog post is an update to the findings of that study which was led by Elizabeth Sowell at The Saban Research Institute of Children's Hospital Los Angeles and Columbia University Medical Center and coauthored by Teachers College faculty member Kimberly Noble.

In a press release, first author Kimberly Noble said, "Specifically, among children from the lowest-income families, small differences in income were associated with relatively large differences in surface area in a number of regions of the brain associated with skills important for academic success."

"While in no way implying that a child's socioeconomic circumstances lead to immutable changes in brain development or cognition, our data suggest that wider access to resources likely afforded by the more affluent may lead to differences in a child's brain structure," Elizabeth Sowell, director of the Developmental Cognitive Neuroimaging Laboratory, emphasized in a press release.

Sowell and Noble believe that their findings suggest that interventional policies aimed at children living in poverty are likely to have the most positive impact on individual brain development and society.

They reiterate that the results do not imply that a child’s future cognitive or brain development is predetermined by socioeconomic circumstances or set in stone. The brain is plastic and can always reshape itself.

John Gabrieli, professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT, and an author on the most recent study draws a similar conclusion. In the MIT press release he said,

Just as you would expect, there's a real cost to not living in a supportive environment. We can see it not only in test scores, in educational attainment, but within the brains of these children. To me, it's a call to action. You want to boost the opportunities for those for whom it doesn't come easily in their environment.

Conclusion: Is it Time to Reduce the Emphasis on Standardized Testing?

In my previous Psychology Today blog post on this topic, I asked the question: "What can we do as parents, policymakers and educators to level the playing field and reduce the inequality between the "haves" and "have nots" when it comes to childhood poverty, brain development, and cognitive function?" I believe one answer may be to take the emphasis off standardized testing.

A January 2015 study found that four out of every ten American children live in low-income families, according to new research from the National Center for Children in Poverty (NCCP) at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health.

Until we can get to the root of the problem and reduce socioeconomic stratification, it seems to me that the achievement gap will only continue to widen—especially if we continue relying on current standardized testing models to gauge academic potential.

On a personal note, I am terrible at taking standardized tests. One of the most unexpected blessings in my life is that because my SAT scores were so low, I had no other real option than to attend Hampshire College. Hampshire is one of the few colleges in the country that doesn't look at SATs as part of the admissions process and doesn't have any tests or grades.

Hampshire's "test blind" pedagogy reflects their commitment to creating fairness in access to educational opportunities. It's also in keeping with Hampshire's mission and academic philosophy. The administrators believe that, "standardized tests more accurately reflect family economic status than potential for college success and that standardized testing can pose racial, class, gender, and cultural barriers to equal opportunity."

In June 2014, Meredith Twombly, dean of admissions and financial aid at Hampshire College, said in a press release,

It is no secret that many colleges base financial aid awards largely or partly on test scores. Financial aid should be used to support students who most need assistance, not to reward those who are good test takers.

We want to be clear that our scholarship aid is meant to reward consistently strong academic performance that is complemented by attributes such as leadership, community engagement, and exceptional creativity. Discipline, passion, and dedication to learning cannot be discerned from a single test score.

I believe that if more academic institutions adopted a "test blind" pedagogy it could help level the playing field between the "haves" and the "have nots" and reverse the trend of an ever-widening achievement gap that is interconnected with family income and brain anatomy.

If you'd like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “Socioeconomic Factors Impact a Child’s Brain Structure”

- “Social Disadvantage Creates Genetic Wear and Tear”

- “Tackling the “Vocabulary Gap” Between Rich and Poor Children”

- “Is the Intense Pressure to Succeed Sabotaging Our Children?”

- “Childhood Family Problems Can Stunt Brain Development”

- “Chronic Stress Can Damage Brain Structure and Connectivity”

- “8 Ways Exercise Can Help Your Child Do Better in School”

- “10 Ways Musical Training Boosts Brain Power”

- “How do Genes Sway the Sensitivity or Resilience of a Child?”

- “Why Does Aerobic Exercise Improve Cognitive Function?”

- "The Neuroscience of Imagination"

- “Childhood Creativity Leads to Innovation in Adulthood”

- "Where Do the Children Play in 2014?"

- “Physically Fit Children Have Enhanced Brain Powers”

- “Why Is the Teen Brain So Vulnerable?”

- “Too Much Crystallized Thinking Lowers Fluid Intelligence”

- "One More Reason to Unplug Your Television"

© Christopher Bergland 2015. All rights reserved.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.