Education

Socioeconomic Factors Impact a Child's Brain Structure

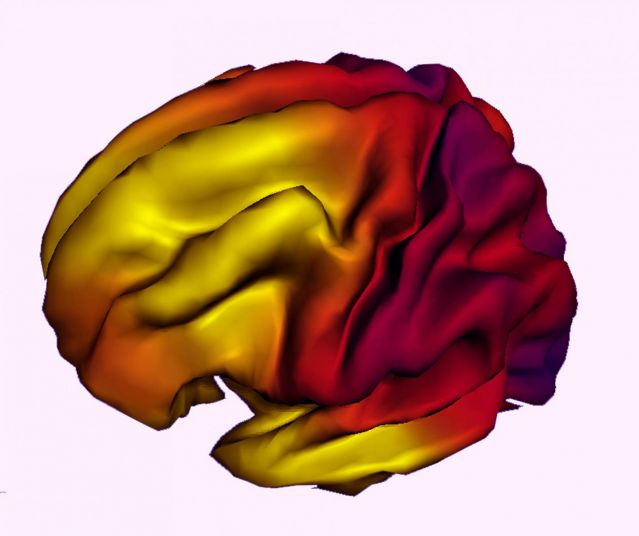

Family income and parental education are linked to a child's brain development.

Posted March 31, 2015

In the largest study of its kind, a team of investigators from nine different universities have identified a correlative link between family income and a child’s brain structure. The correlation between brain structure differences and family income were the most dramatic in lower-income families.

The March 2015 study, “Family Income, Parental Education and Brain Structure in Children and Adolescents,” was published in the online edition of the journal Nature Neuroscience.

The new study was led by Elizabeth R. Sowell, PhD at The Saban Research Institute of Children's Hospital Los Angeles and coauthored by Teachers College faculty and Columbia University Medical Center member Kimberly G. Noble, MD, PhD.

The sample for this study included more than 1,000 typically developing children and adolescents between the ages of three and 20 years old. The researchers found that higher levels of parental education and family income were associated with increases in the surface area of numerous brain regions—including those responsible for language and executive functions. Family income level appeared to have a stronger correlation with brain surface area than parental education.

In a press release first author Kimberly Noble said, "Specifically, among children from the lowest-income families, small differences in income were associated with relatively large differences in surface area in a number of regions of the brain associated with skills important for academic success."

On the flip side, children from higher-income families and the incremental financial differences between upper income families were associated with much smaller differences in surface area. Higher income was associated with better performance in certain cognitive skills—cognitive differences that could be accounted for, in part, by greater brain surface area according to the researchers.

The researchers emphasize that these findings suggest that interventional policies aimed at children living in poverty are likely to have the most positive impact on individual brain development and society.

The results do not imply that a child’s future cognitive or brain development is predetermined by socioeconomic circumstances or set in stone. The brain is plastic and can always reshape itself.

"While in no way implying that a child's socioeconomic circumstances lead to immutable changes in brain development or cognition, our data suggest that wider access to resources likely afforded by the more affluent may lead to differences in a child's brain structure," Elizabeth Sowell, director of the Developmental Cognitive Neuroimaging Laboratory, emphasized in a press release.

40 Percent of American Children Currently Live in Low-Income Families

A January 2015 study found that four out of every ten American children live in low-income families, according to new research from the National Center for Children in Poverty (NCCP) at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health.

The findings from the 2015 edition of the center's Basic Facts about Low-Income Children illustrate the magnitude of the problem of family economic insecurity and child poverty in the United States. The statistics are alarming:

- The number of children in economically insecure families remains far higher than it was before the Great Recession. Although the number of children under age 18 in the U.S. has grown by less than one percent since 2007, the number of poor children has grown by 23 percent (almost three million) and the number of low-income children has grown by 13 percent (3.6 million).

- Very large disparities in family economic security by race and ethnicity persist. More than 60 percent of African American, Latino, and American Indian children live in low-income families, compared to about 30 percent of white and Asian children.

- Many poor children have parents with some college education. Forty-one percent of poor children have at least one parent with some college education.

- Many poor and low-income children live with working parents. Half of low-income children and 29 percent of poor children live with at least one parent employed full time, year round.

- Younger children are more likely to live in low-income families than older children. Forty-seven percent of all children under 3 years old live in low-income families, compared to 41 percent of children age 12 through 17 years.

- The percentage of children in low-income families varies substantially by region. Forty-eight percent of children in the South live in low-income families, compared to 37 percent in the Northeast.

Cognitive Training Improves Brain Performance of Students Living in Poverty

A December 2014 study from the Center for BrainHealth at The University of Texas at Dallas found that the cognitive effects of poverty can be mitigated during middle school with a targeted intervention. The study, "Enhancing Inferential Abilities in Adolescence: New Hope for Students in Poverty," was published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

In this groundbreaking study, the BrainHealth researchers studied the efficacy of cognitive training in a large and diverse group of 7th and 8th grade public middle school students and compared the findings to typically developing students who received no specific training.

Dr. Jacquelyn Gamino, director of the Center for BrainHealth's Adolescent Reasoning Initiative, said in a press release, "Previous research has shown that growing up in poverty can shape the wiring and even physical dimensions of a young child's brain, with negative effects on language, learning and attention. What this work shows is that there is hope for students in poverty to catch up with their peers not living in poverty."

For the 556 students who received the Center for BrainHealth-developed cognitive training called SMART (Strategic Memory Advanced Reasoning Training), they completed 10 45-minute sessions over a one-month period.

The SMART program was provided by research clinicians and consists of hierarchical cognitive processes that are explained and practiced through group interactive exercises and pen and paper activities using student instructional manuals.

"Much focus has been put on early childhood learning and brain development—and for good reason," said Dr. Gamino. "However, extensive frontal lobe development and pruning occurs during adolescence making middle school a prime opportunity to impact cognitive brain health." Dr. Gamino concluded:

Existing studies show that a large percentage of students in middle school are not developing inferential thinking entering high school. The cognitive gains demonstrated after short-term, intensive training in this research suggest that middle school is an appropriate and beneficial time to teach students strategies to enhance understanding and the ability to infer global meanings from information beyond the explicit facts.

Conclusion: Targeted Interventions Can Change the Trajectory of Brain Structure

What can we do as parents, policymakers and educators to level the playing field and reduce the inequality between the "haves" and "have nots" when it comes to childhood poverty, brain development, and cognitive function?

Family income is linked to many health factors such as nutrition, health care, school quality, access to safe play areas, air pollution, etc. Everything that a child is exposed to in the home and neighborhood environment has the potential to impact his or her developing brain.

Ultimately, I believe that we need to address the root of this problem and take a multi-pronged approach that reduces socioeconomic stratification and the number of Americans living in poverty.

Kimberly Noble concluded, “We can’t say if the brain and cognitive differences we observed are causally linked to income disparities. But if so, policies that target poorest families would have the largest impact on brain development."

Hopefully, this type of research will mobilize the powers that be to create social policies that reduce family poverty and optimize healthy brain development for all children. Policy changes could dramatically improve the trajectory of brain development for children from all socioeconomic strata—but especially for the most vulnerable living in lower-income households or poverty.

If you'd like to read more on this topic, check out my Psychology Today blog posts:

- “Social Disadvantage Creates Genetic Wear and Tear”

- “Tackling the “Vocabulary Gap” Between Rich and Poor Children”

- “Childhood Family Problems Can Stunt Brain Development”

- “Chronic Stress Can Damage Brain Structure and Connectivity”

- “8 Ways Exercise Can Help Your Child Do Better in School”

- “10 Ways Musical Training Boosts Brain Power”

- “Is the Intense Pressure to Succeed Sabotaging Our Children?”

- “How do Genes Sway the Sensitivity or Resilience of a Child?”

- “Why Does Aerobic Exercise Improve Cognitive Function?”

- "The Neuroscience of Imagination"

- “Childhood Creativity Leads to Innovation in Adulthood”

- "Where Do the Children Play in 2014?"

- “Physically Fit Children Have Enhanced Brain Powers”

- “Why Is the Teen Brain So Vulnerable?”

- “Too Much Crystallized Thinking Lowers Fluid Intelligence”

- "One More Reason to Unplug Your Television"

- “Physical Activity Empowers Kids to Achieve Personal Bests”

© Christopher Bergland 2015. All rights reserved.

Follow me on Twitter @ckbergland for updates on The Athlete’s Way blog posts.

The Athlete’s Way ® is a registered trademark of Christopher Bergland.