Growth Mindset

Growth Mindsets Foster Excellence Because We Don't Give Up

People don't try hard if they don't think it will make a difference.

Posted February 3, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Dweck's theory of mind tells us that those who focus on talent are more likely to quit when they run into difficulties.

- Learners who have growth mindsets believe performance comes from effort, so they learn from their mistakes.

- Growth mindsets and good performance develop when we praise neither talent nor effort, but foster mastery orientation.

Physics has gravity. (It’s not just a good idea; it’s the law.)

Psychology has social learning theory. Bandura’s extension of the stimulus-response models of behaviorism to include cognition and learning from others is so fundamental to psychology’s core paradigm that we rarely study it directly anymore.

Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory of Behavior

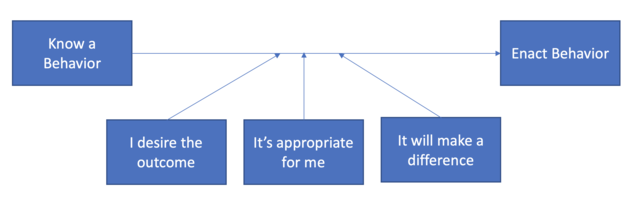

Bandura argues that whether or not we do something is determined by

- Whether we know the behavior,

- Whether we desire the outcome the behavior will produce,

- Whether we believe the behavior is appropriate for ourself, and

- Whether we believe enacting the behavior will make a difference in the outcome.

Why Do Dogs Perform Tricks?

My dog, Loki, competes in Rally Obedience. When I give him a command, however, he doesn’t always perform it. Why?

Say I give him the command "down."

- First, Loki needs to know that the word "down" is associated with the specific behavior I’m looking for (full down with elbows on the ground in a particular context-specific orientation to me).

- Second, Loki needs to desire the outcome that enacting that behavior will get him—in this case, a treat. When I really want him to perform, I use "high-value treats" (dried liver) instead of basic kibble. And he is much more eager to work when he’s hungry than when he’s not.

- Third, Loki needs to know I’m talking to him. Interestingly, Loki won’t sit or "down" when I’m speaking to another dog, even though he’s with me. He responds when we’re training or working together, but if he isn’t "on," he doesn’t work. It's not appropriate to him.

- Most importantly, Loki needs to know that his behavior will make a difference in the outcome. Studies have shown that the biggest difference between successful and unsuccessful trainers is consistency. First, the dog is clear what the trainer is asking for. But then, when the dog does what is asked for, their trainer responds positively to correct performance and the dog is rewarded. The dog needs to know their behavior will matter. Obedient dogs expect obedience to be rewarded.

Importantly, it’s not just getting rewarded that improves performance—eating lots of dried liver does not make Loki smarter! Dogs perform most consistently when they are rewarded for enacting the correct behavior and not rewarded when they don’t. In other words, good dogs get treats!

Growth Mindset and Theory of Mind

Carol Dweck’s growth mindset has rightly received a great deal of attention, particularly in educational circles. Her work on theory of mind examines the role of people’s beliefs about performance and how it influences their behavior in difficult learning tasks.

In its simplest form, Dweck argues that when learning a new task, people bring different theories of mind to the setting. Theory of mind answers one key question: Why are some people better at this than others?

Let’s say we’re watching a bunch of kids shooting hoops. Some are nailing their shots from far out in court. Others are missing shots a few feet from the basket, the ball bouncing off their sneaker in a misguided dribble.

- Entity theories. If we hold an "entity" theory of mind, we’re more likely to say things like “They’re a natural!” In other words, we attribute skill mostly to talent—something fixed that they have. Some of us are good at sports; some of us aren’t.

- Growth theories. If we hold a "growth" theory of mind, we’re more likely to see differences as coming from work and effort. Importantly, we’re much more likely to believe that, although some of us may have more natural ability at sports, drills, practice, and attention will make all of us better.

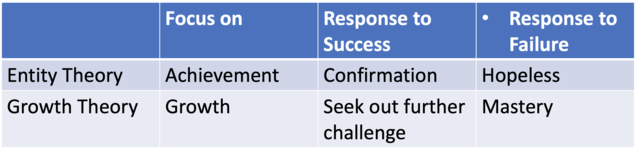

The figure above describes how people who differ in their theory of mind come into new and challenging learning situations.

Let’s take an average someone with an entity theory of mind.

- When learning something new, they look at their performance and see how good they are at it. In other words, this is all about talent! How much do I have?

- When they do well, they see it as confirmation that they are awesome.

- When they don’t do well, they know they have little talent. Since that’s fixed—you’ve got it or you don’t—when they do poorly, they tend to give up.

Someone with a growth theory of mind will approach tasks differently.

- They go into a new situation seeing how much they need to work to achieve excellence.

- Because they believe their ability grows when they learn new skills, they seek challenge. In other words, ability is like a muscle. The more you exercise it, the stronger (smarter) you get.

- When they run into problems, they show a mastery orientation. They focus on their errors. They figure out what they are doing wrong. They ask for help.

Self-Esteem Matters

In looking at this model, it's critical to distinguish between people holding each of these belief systems who have high and low self-esteem. Specifically, we need to understand how much ability do different learners think they have.

Why? Because their theory about ability determines how they respond.

- I believe in talent and I have a lot of it! Someone who believes they are "talented" will go into a new situation looking for ways to prove to themselves that this is true (confirmation). Dweck has found they often show a mastery orientation, drilling down even though they think their poor performance must be because the task is hard or the teacher is unfair. If they focus and succeed under those conditions, they must be pretty awesome indeed!

- I'm bad at art. Low-self-esteem learners holding entity theories are more likely to attribute their failure to their low ability. Having confirmed that they're just bad at this task, no amount of trying will help. Over time, they seek out easier tasks and those they are good at because those tasks allow them the rewards they are looking for—good performance.

- Give me a challenge! Self-esteem plays much less of a role in how growth mindset learners approach tasks. If they don’t think much of their ability, working the problem will make them better. If they do well initially, give them a harder task! Those most likely to seek out challenges and continue to grow and improve are those with low self-esteem and a growth mindset. Over time, these learners seek out more and more difficult tasks, building skills over time.

Fostering Growth Mindsets

Behaviorism and social cognitive theory have taught us that reinforcement is subtle. That's true for the development of growth mindsets as well. Telling a child "You're smart!" tells them two things. One, it may bolster self-esteem. But, two, it reinforces the idea that performance is about ability, fostering an entity mindset.

Rewarding effort is not the answer either. The goal of learners with both orientations is good performance—which means you're always upping the goals and trying harder tasks.

It is critical to teach the process. Teach and praise mastery orientation.

- Ask key questions: Where are you running into problems? What's another way to approach it?

- Praise thoughtful appraisal: Love the new strategy. You're right, that's not working, but that new technique is getting closer.

Authentic praise of a mastery approach focuses learners on where they should be focused— developing strategies that result in excellent performance and growth over time.