Cognition

How Did Human Self-Consciousness Evolve?

Human self-consciousness evolves in a field of questions and answers.

Posted July 26, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Human consciousness is different because of the evolution of propositional speech.

- Through questions and answers, propositional speech generated the problem of justification.

- Human self-consciousness is about generating justification systems for one's self and others.

What makes human consciousness unique? Why did it evolve the way it did? How do we know? Interestingly, the simple act of posing these questions gives us a major clue as to what the answer is.

According to the Unified Theory of Knowledge (UTOK)1, the key to understanding human consciousness is to focus carefully on how the evolution of propositions is tightly associated with the capacity to ask questions. This, in turn, gives rise to the problem of justification. And it was the problem of justification that drove human consciousness in a new direction.

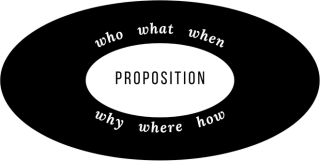

A proposition makes a positive meaning claim. For example, the statement, “The antelope are over that hill,” means that a particular kind of creature resides in a specific place. The process of making a claim opens “negative” space around it. The negative space challenges the claim, and it can be pointed to via questions (i.e., How do you know? Could they be gazelle? What does it mean for us?).

Consider words like who, what, when, where, how, and why. These question stems can be thought of as docking into the proposition and opening up the adjacent negative space. This tension between the positive space taken up by propositions and the negative space opened up by questions is something UTOK calls the question-answer dynamic. This is crucial to understand because it results in the evolutionary tipping point that transformed us from primates into self-conscious persons who are developmentally socialized to become actors on the cultural stage.

Why does the emergence of propositional speech and questioning result in an evolutionary tipping point? One reason is that asking questions is relatively easy. To see why this is the case, spend some time with a curious 4-year-old. They are likely to pepper you with questions, such as “Why don’t we eat cookies before we eat dinner?”; “Why are you bald?”; “Why is the sky blue?” As children readily demonstrate, asking questions is much easier than answering them. That is why exasperated parents eventually say, “That is just the way it is!”

This observation suggests that the capacity to ask questions necessarily motivated the search for answers. UTOK calls the problem of generating legitimate answers to questions the problem of justification. And it was the problem of justification that drove the evolution of human consciousness in a unique way.

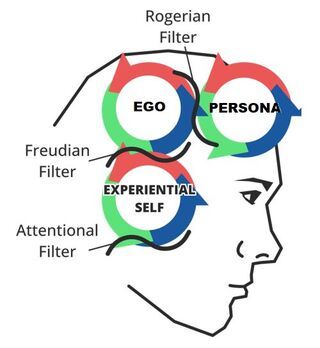

To see this, take a minute and divide your conscious experience into three broad domains. First, there is your subjective conscious experience of being in the world. This includes your perceptions of the outer world via your hearing and vision, your felt sense of your body in the world, and the images you have about possible worlds. UTOK calls this your primate, experiential self, and it is the kind of consciousness you share with other mammals.

Now orient toward the private narrating part of your consciousness. This is the “I” that narrates what is happening and why. Consistent with Freud, UTOK calls this your ego. Now think about how other people see you and how you manage your social impressions. This is your persona. Your primate experiential self, your private ego, and your public persona are the three primary domains of human consciousness.

How does this connect to the problem of justification?

Well, the ego and the persona are both organized by it. That is, they are networks of propositions, dynamically generated by claims and questions that result in systems of justification that work to legitimize what is and ought to be. And there are two major domains in which this legitimizing takes place. The ego is tasked with developing justifications privately, in what Martin Buber called the “I-me” relation. The persona is tasked with developing justifications publicly, in what Buber called the “I-thou” relation.

We can see the dynamics of justification in the filters between the major domains of human consciousness2. UTOK calls the filter between the experiential self and the ego the Freudian filter. This is because Freud’s fundamental insight was that the ego works to develop a justifiable narrative relative to our more basic, animalistic perceptions and urges. The “I-thou” filter, or private-ego-to-public-persona filter, is called the Rogerian filter because of the profound insights Carl Rogers made regarding ourselves and the social world. He realized that much of human consciousness and misery relates to how the judgment of others shapes our actions and the sense we have of ourselves.

Returning to the questions that started this essay: What makes human consciousness unique, why did it evolve, and how do we know? Human consciousness is unique because, in addition to the primate experiential world of subjective perceptions, motives, and emotions, human consciousness has an additional layer of justification mediated by language. This domain is what is primarily developed as we are socialized to become persons in a culture. There is a private domain, characterized by justifications to the self, and a public domain, characterized by justifications to others. These domains evolved because of the adaptive problem of justification that arises out of the emergence of Q-A dynamics. If you don’t think this proposal for human self-consciousness is justifiable, I invite you to engage in it. So please, by all means, raise questions and try to generate better answers.

References

1. Henriques, G. (2022) A new synthesis for solving the problem of psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave.

2. Henriques G. (2022, March). The three filters of consciousness. Theory of Knowledge blog.