Self-Control

Exercise Psychology: What It Is And Why It Matters

Why you exercise may be more important than how you exercise.

Posted May 16, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Exercise psychology refers to how you think and feel about exercise.

- One's exercise psychology can be either negative or positive depending on prior experiences and emotions.

- A negative exercise psychology is common and makes it difficult and unrewarding to exercise.

- Developing a positive exercise psychology requires new reasons, experiences, and emotional connotations.

What comes to mind when you think about exercise?

For example:

- What types of physical activities do you imagine (e.g., walking/running, using a cardio machine, weightlifting, yoga classes, etc.,)?

- What locations do you associate with exercise (e.g., an outdoor trail, neighborhood sidewalk, gym, your living room, etc.,)?

- Most importantly, what thoughts and feelings do you experience when you recall or envision exercise (e.g., is it closer to adventure, self-improvement, and socializing, or to calorie counting, pain, and fat shaming)?

Whatever forms, settings, memories, and emotions you identified in response to the above three questions, this is your exercise psychology. It captures the fundamental way that you think about and feel about exercise. And it matters. Probably more than you assume.

Your exercise psychology, for instance, greatly determines:

- Whether or not you will be able to maintain a regular exercise routine, irrespective of your income, age, education, or health status.

- How much willpower and self-discipline you will need to start or keep exercising.

- How much you enjoy exercise.

- Your lifetime risk of exercise-related health conditions (cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic pain, dementia, and diabetes, among many others).

Two exercise psychologies, two results

For people with a negative exercise psychology (i.e., possessing negative memories, thoughts, and feelings associated with exercise), they are likely to be more sedentary, avoid and dislike exercise, have a "no pain, no gain" personal history with exercise, and be more likely to suffer from forms of disability and disease that result from a lack of exercise. Meanwhile, people with a positive exercise psychology (i.e., possessing positive memories, thoughts, and feelings associated with exercise) generally experience all the positive physical and mental health benefits of exercise without the struggle. For the latter group, exercise is a consistent source of pleasure. For the former group, meanwhile, exercise more often feels like punishment.

Now for the bad news: Americans, overwhelmingly, have a negative exercise psychology. Unfortunately, until that changes — individually and collectively — we will continue to suffer the consequences.

Exercise psychology: how it begins and becomes corrupted

Humans are born into the world with a biologically-based positive exercise psychology. Our brains are so preferentially wired for physical movement that we have built-in pleasure circuits to promote and reward it. Dopamine, one of the primary neurotransmitters associated with pleasure and reward, for instance, is strongly activated by physical movement and exercise1. Perhaps without realizing it, you've seen this biological disposition among young children, whose innate tendency to climb, play, squirm, and fidget brings frequent consternation from parents. The brains of these children are chemically programmed to love movement.

But all this begins to change during school years. Spontaneous movement suddenly becomes forbidden, regulated, and even punished. Children are instead trained to sit for long periods. Physical play is limited to structured recess times, and any physical activity built into the school curriculum is in the form of PE classes. Rather than recreational movement, however, PE more likely consists of calisthenics, fitness tests, competition, and social comparisons. For many children, this environment causes them to accumulate more and more adverse experiences associated with exercise. They begin developing a negative exercise psychology2. Among many of these children, this psychological change will last long into adulthood.

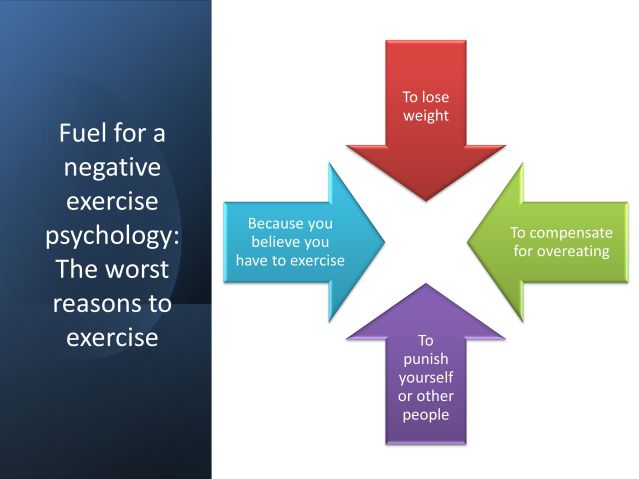

Adulthood in the U.S., sadly, usually offers no remedy for negative exercise psychology. Instead, adult experiences with exercise typically magnify the aversive lessons already learned during childhood. As shown in Figure 1 above, most U.S. adults learn and model four psychologically corrosive reasons for exercising: weight loss, dietary compensation, obligation, and as a form of physical or emotional punishment. Each one — and many people have several — adds the equivalent of emotional lead to the weight of their negative exercise psychology, making it unpleasant to exercise and difficult to be consistent.

In combination, these child and adulthood factors ruin the experience of exercise. They make well-intended Surgeon General guidelines, doctor's advice, and even the latest wearable technology minimally effective for exercise promotion3. And this negative exercise psychology predisposes us to suffer the physical and emotional consequences of living in bodies physically designed to move but emotionally compelled to remain still.

Restoring a positive exercise psychology

Exercise research reveals a curious conundrum: most people know about the importance of exercise yet only a minority achieve recommended exercise levels. Similarly, most people appreciate the health benefits of exercise, yet just 20-30% actually enjoy exercise4. This research suggests that knowledge and awareness about exercise in the U.S. are common but that this information isn't empowering.

What this research seems to suggest is that the gap between exercise knowledge and practice is less about facts and more about fun. Specifically, the subgroup of Americans who engage in consistent exercise throughout their lives and experience the most exercise benefits share the quality of having positive rather than negative attitudes about exercise5. The question many people have is how can they get this positive exercise attitude after a lifetime of exercise negativity?

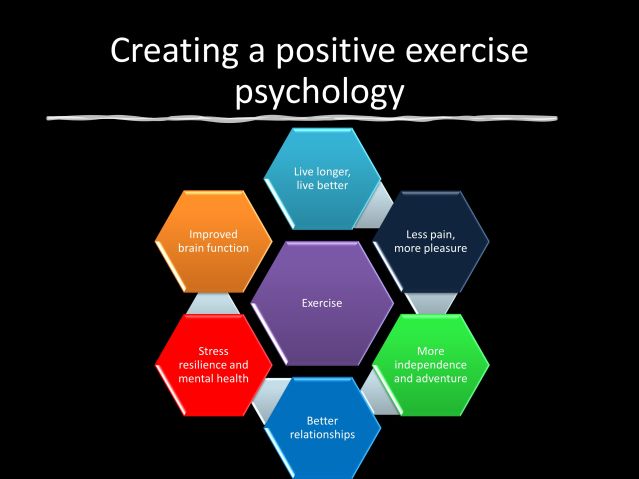

Figure 2 offers some basics for restoring positive exercise psychology. Although there are no internet hacks or quick fixes that will renew a person's native love for exercise, there are mental, behavioral, and social practices that can dramatically improve their exercise experience over time.

- Firstly, becoming a person with a positive exercise psychology requires replacing the negatively-charged exercise reasons from Figure 1 with one or more of the positively-charged reasons in Figure 2. Instead of exercising for weight loss, for example, or to make up for a poor diet, exercise to improve your friendships and family life, to improve energy and vitality, to increase novelty and adventure, or to obtain a sense of growth and progress in your life. The right reasons to exercise are those that make you feel good about exercising. The wrong reasons make you feel bad.

- Second, put fun at the top of the list for your exercise program ingredients. If the exercise isn't enjoyable or rewarding in some meaningful way to you, don't do it. Forcing yourself to engage in toilsome exercise simply reinforces a negative exercise psychology that will make it only harder to remain physically active in the future.

- Thirdly, think about the most engaging form, style, and environment in which you can exercise. Exercise that you don't do doesn't improve your quality of life. Don't settle for the convenience of home exercise equipment or virtual classes if they feel empty to you. The right people and setting can transform an exercise grind into one of the peak experiences of your day. And turning exercise into something that you look forward to and see regular progress from will help turn exercise into something that you want to make a priority in your day.

Summary

After all these years, today could be the day that you decide to change your relationship with exercise for the better. Until you do, you'll probably keep getting the same old results.

References

1. Marques A, Marconcin P, Werneck AO, Ferrari G, Gouveia ÉR, Kliegel M, Peralta M, Ihle A. Bidirectional Association between Physical Activity and Dopamine Across Adulthood-A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2021 Jun 23;11(7):829. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11070829.

2. Chad D. Jensen, PhD, Christopher C. Cushing, PhD, Allison R. Elledge, MA, Associations Between Teasing, Quality of Life, and Physical Activity Among Preadolescent Children, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 39, Issue 1, January/February 2014, Pages 65–73, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst086

3. Fawcett E, Van Velthoven MH, Meinert E. Long-Term Weight Management Using Wearable Technology in Overweight and Obese Adults: Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Mar 10;8(3):e13461. doi: 10.2196/13461.

4. Poobalan, A.S., Aucott, L.S., Clarke, A. et al. Physical activity attitudes, intentions and behaviour among 18–25 year olds: A mixed method study. BMC Public Health 12, 640 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-640

5. Timothy D. Nelson, PhD, Eric R. Benson, MA, Chad D. Jensen, MA, Negative Attitudes Toward Physical Activity: Measurement and Role in Predicting Physical Activity Levels Among Preadolescents, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 35, Issue 1, January/February 2010, Pages 89–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsp040