Education

Bored at School

Why giving kids more control might alleviate boredom in the classroom.

Posted October 15, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Boredom is common in the classroom and can have negative impacts on learning.

- The key drivers of classroom boredom are a lack of control and meaning.

- When kids lead their own learning, we can keep boredom at bay.

It’s a common refrain from children and adolescents—“I’m bored!” Perhaps even worse is the equally common complaint, “School is boring!” And they are not just making it up.

Research shows that in high school students, boredom is experienced at school around one-third of the time! In a large experience sampling study in the USA, when people did report being bored, it was most commonly experienced when studying (boredom was 4-6 times more often associated with study than it was with exercise). To top it all off, there might be some subjects—sorry to say it, but math is the most prominent culprit[i]—that are better boredom promoters than others.

While we have more data from adolescents and university students than we do for primary school-age children, it seems reasonable to assume that boredom doesn’t suddenly appear in the teenage years. Clearly, boredom is prominent in education settings, and it is not without consequence. Not only is boredom in school associated with poor academic outcomes (even in university students), but recent research has also shown it to be associated with lower levels of mental well-being.

But what are the causes of boredom in school?

Is learning itself inherently boring? As life-long learners ourselves, we would hope not! And certainly, a curious mindset has consistently been associated with positive mental well-being.[ii] As is the case for antecedents to boredom in other circumstances, monotony and a lack of meaning seem to be powerful drivers of boredom in the classroom. A third determinant—time—is also critical. Boredom lurks just around the corner when things drag on for too long.

It is not as though this is news to most of us! Since universal education became a goal in the West, it has been evident that our structures and strictures have recognized the burden of boredom. Or perhaps more accurately, the need to encourage focused attention.

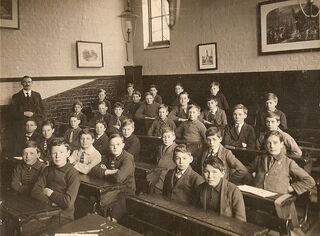

We line desks and chairs up in neat rows. We structure learning and playtime in regimented schedules reminiscent of incarceration. Our earliest designs of classrooms from the early part of the 20th century had the placement of windows well above eye-level—so-called Bell-Lancaster designs. Anything to prevent “wandering eyes” from being distracted from the didactic lessons of the moment.

All of this was aimed at controlling the students’ attention, preventing distraction, so the little sponges could absorb the revelations we deemed necessary. But this turns the pupil into a passive recipient of knowledge, as opposed to an active, curious seeker.

One prominent theory of boredom in school comes from Reinhard Pekrun and his colleagues, who suggest there are two primary drivers at play—control and value. For any given activity, if students feel they have no autonomy and the task seems pointless, boredom will inevitably arise. Time and monotony likely represent key determinants of control and value, respectively. When our time is not our own—when we must persist with an activity we’d rather abandon—we likely feel a loss of agency or control. And all things monotonous lack meaning.

In that context, research has shown that there are optimal ways to cope with boredom in the classroom. Broadly speaking, students can engage in behavioral or cognitive coping strategies—put crudely, do something else vs. re-think the situation. While engaging in behaviors that might help a student escape the doldrums of the immediate circumstance (e.g., acting out in class) may temporarily relieve boredom, they do not provide a long-term or desirable outcome. Instead, the best approach is to reframe the task. Think about it in different ways that elevate it to something meaningful to you.

In one study using a participatory design (otherwise known as collaborative inquiry) to better understand how children experience boredom in the classroom, time and control were the key factors raised. One student even said that anything can become boring if you do it for long enough! Even for math, that most hapless of topics for avoiding boredom, students in this study said that it was tolerable so long as you don’t have to do it for so long.

All this highlights the need to give students some amount of autonomy in how they learn. This can even come down to architecture. In designing our buildings for learning, we have often sought to engender an environment that promotes focused attention—high windows, regimented desk assignments.

But what happens when we design for and promote autonomy?

The approach is perhaps best personified in the well-vaunted Montessori system, first implemented in the early part of the 20th century by the system’s namesake, Maria Montessori. A key facet of this pedagogic philosophy is self-directed learning. While the system may not be suitable for all people in all circumstances, the fact that it promotes autonomy may go a long way to preventing boredom in the classroom.

There may be ways in which we can change our approach to education without engaging the more substantive changes inherent to Montessori while still achieving much the same thing—increased autonomy and a sense of curiosity. Schools in Scotland have led the way in outdoor education, a system with fewer boundaries and more chance for serendipity—not to mention a potentially excellent way to educate during a pandemic!

In a recent ethnographic study of boredom in the classroom, when high school students asked a teacher, “Why are we learning this?” they were told, “Because it is on the test.” It is a truism that in the West, we teach to a curriculum and evaluate the success of our teaching by scores on standardized tests. But all this bypasses any consideration of intrinsic motivation in the learner. Students need to see the “why” in order to appreciate the meaning and purpose of their lessons.

Working towards a test score determined by a faceless bureaucracy represents an extrinsic motivator. We know that intrinsic motivations, the goals we decide for ourselves to be of value, are far more powerful in driving us towards desired goals. We may not need a full Montessori approach or full-time outdoor classrooms (although more of this is undeniably good), but giving students more control over what they are curious to learn about will almost certainly minimize boredom.

We are engaged with the scientific process not because we see some definable end in sight but because the journey is one of discovery. And each new discovery leads to more questions. To keep boredom at bay, we should foster that curiosity in our kids, and the best way to do that is to let them lead the way.

References

[i] There’s quite a bit of research on boredom and math – this is just a sample: Putwain, D. W., Pekrun, R., Nicholson, L. J., Symes, W., Becker, S., & Marsh, H. W. (2018). Control-value appraisals, enjoyment, and boredom in mathematics: A longitudinal latent interaction analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 55(6), 1339-1368. Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2007). Perceived learning environment and students' emotional experiences: A multilevel analysis of mathematics classrooms. Learning and Instruction, 17(5), 478-493. Pekrun, R., Hall, N. C., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Boredom and academic achievement: Testing a model of reciprocal causation. Journal of educational psychology, 106(3), 696.

[ii] It should be pointed out that this research showed that high curiosity promoted mental well-being but that there was no negative outcome for low levels of curiosity.