Neuroscience

New Brain Maps Advance Understanding, With Limitations

A tale of two brain atlases.

Posted November 12, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- The U.S. BRAIN Initiative and the European Human Brain Project have produced very different "brain atlases."

- The BRAIN Initiative revealed the genetic makeup of more than 3,300 types of brain cells.

- The Human Brain Project produced a multilevel brain atlas and made it publicly available.

- The social and philsophical implications of both projects deserve consideration.

This fall, Europe's Human Brain Project (HPB) and the U.S.'s BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative announced the results of their efforts to create a comprehensive atlas of the brain.

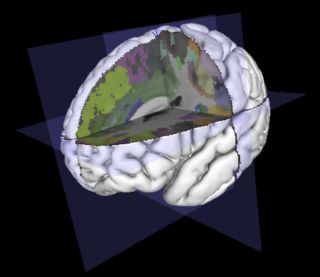

Europe's HBP has created "the most detailed," interactive, and publicly accessible 3-D brain models to date, with variations for humans, non-human primates, mice, and rats. The model maps the shape, location, and variability of brain structures as well as the architecture of nerve fibers and cells, cortical and sub-cortical layers. While the NIH-funded BRAIN has yet to build an interactive model of the human brain, it has published 24 papers detailing the genetic makeup of more than 3,300 types of brain cells (with more on the way). One of the project's expected outcomes is "An open-access 3-D digital brain cell reference atlas with molecular, anatomical, and physiological annotations of brain cell types in mice."

Announced by Barack Obama in 2013, the BRAIN Initiative's goal, now partially realized, was "to produce a revolutionary new dynamic picture of the brain that, for the first time, shows how individual cells and complex neural circuits interact in both time and space." Its publications in major scientific journals offer the details of the results so far. For the moment, these papers are a stand-in for a brain atlas in the making. So far, BRAIN has not produced an interactive model, but has produced the data that promises to yield one that includes granular details about the roles particular brain cells play and their genetic components.

The Human Brain Project's goals have always been more diffuse: "The Human Brain Project has contributed to a deeper understanding of the complex structure and function of the human brain with a unique interdisciplinary approach at the interface of neuroscience and technology." While BRAIN's atlas is revolutionary in its identification of cell types and functions, the Human Brain Project's equivalent is more expansive, modeling brain activity that may provide insight into a variety of fields, including robotics, artificial intelligence, neural implants, and the study of consciousness.

The BRAIN Initiative's Results are impressive. More than a thousand research projects across the globe, funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), have identified more than 3,300 types of brain cells (with more to be identified). Collectively, they've documented the complete genetic makeup of each cell type, identified which cells are active in particular brain systems, and developed a greater understanding of cell connectivity across brain structures—toward the development of identified a brain "connectome." In concrete terms, this new knowledge promises to illuminate little-understood brain conditions—for example, Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer's disease.

The HPB's results are impressive, too, though quite different. More than 500 researchers representing 155 institutions in 19 countries have developed more than 160 new digital tools that manage data, simulate brain activity, and facilitate research across fields and labs. The multi-level HPB atlas "captures information about brain variability in different subjects and accumulates knowledge from various neuroscientific sources both at the microscopic and macroscopic scales... Based on microstructural principles, it builds links between MRI-based reference spaces to the microscopic BigBrain model." The HPB has produced 3-D models of human, monkey, mouse, and rat brains

The HPB atlas is more immediately available and applicable, while the BRAIN Initiative promises perhaps greater long-term understanding of brain function at the cellular level. The remarkable research and promise of both projects have been widely reported. Yet the social implications of the two projects are less well-understood. Those two projects developed along the same timeline, so the idea that they were in a 'race' to explain the human brain was irresistible. But it is also misdirection. The two projects used different methodologies and led to different outcomes.

By definition, a brain atlas is a composite portrait of a so-called neurotypical brain. While the brain atlas project emphasizes the diversity of cell types, it doesn't yet have the capacity to tell us much about the diversity of humans—and their brains. An atlas is always a work in progress. In its current version, the brain atlas reveals a tension between understanding the brain and understanding individual brains.

Henry Markram, Swiss Neuroscientist and Co-Director of the Human Brain Project, has hoped from the beginning that brain atlas projects will enable us to understand the differences between individual brains. Markram is also the father of Kai Markram, whose autism he cites as a personal motivation for his ambitious (and sometimes bizarre) goals for the project: “To be able to dial up everything, the colours, the sounds—that’s what motivates me... To be able to step inside a simulation of my son’s brain and see the world as he sees it. At the moment, I can use fMRI and ECG [electrocardiogram] to see how the brain processes information and which regions are activated during different tasks but I can’t see what it is perceiving, I can’t see what it sees.”

Markram's goal sounds like science fiction, but so would have the idea of a brain atlas 50 years ago. His fantasy is a reminder that both projects are motivated by philosophy and politics, in addition to science and medicine. Philosophers use the term "explanatory gap" to refer to the gap between knowledge of the physical brain and the ability to explain how brains enable us to think, feel, and be. Advocates of neurodiversity remind us that no two brains are alike—and that we are often too quick to diagnose brain differences as brain disorders.

Neither of the brain atlas projects fulfills Markram's fantasy, but that fantasy is a reminder that science is a social endeavor. As neuroscientists all over the world pursue medical and scientific goals made possible by brain atlases, we should all keep in mind the philosophical and social implications of the projects. We can't yet explain the relationship between brain and self, and we lack definitive explanations of brain-related conditions like schizophrenia, autism, or depression. In fact, we're not even sure these conditions arise from similar causes between one person and another. As the saying goes, "If you've met one autistic person, you've met one autistic person."

References

Honigsbaum, Mark. "Human Brain Project: Henry Markram Plans to Spend €1bn Building a Perfect Model of the Human Brain." The Guardian (October 13, 2013).

Markran, Henry. Tania Rinaldi, Kamila Markran. Frontiers in Neuroscience (November 1, 2007 Nov): 77–96.