Serial Killers

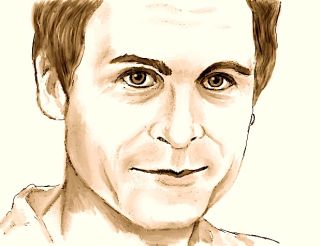

5 Myths About Serial Killer Ted Bundy: Why They Persist

Dogmatic cognitive styles might account for the popular myths about Bundy.

Updated July 5, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- The infamous serial killer Ted Bundy has inspired some claims with no basis in fact.

- Debunking these claims with facts has failed to erase the misconceptions about Bundy.

- A study reports when something personal is at stake, such as ego, discrediting with facts has little impact.

Ted Bundy has been the subject of more media focus than any other modern-day serial killer. Certain notions show up in many accounts, including some proven to be false.

What’s the deal? Why do we retain such claims? There might be a personal investment that feeds resistance, but some people just accept information that seems to solve a mystery. Thus, misconceptions persist.

I’ve invited Kevin Sullivan, the author of six books about Bundy, to assist with this list. It’s not exhaustive, but these five myths show up repeatedly.

1. Sam Cowell, Bundy’s grandfather, was really his father via incest. This was conclusively disproven in 2020 when psychiatrist Dorothy Otnow-Lewis had a copy of Ted Bundy's DNA sequence tested for a key genetic indicator of incest. She'd received the DNA info from Mike McCann, who’d tested a licked stamp from Bundy's letter to his girlfriend. Cowell was not his father.

2. Bundy’s victim type is a female with long, dark hair parted in the middle because that was the hairstyle of a college girlfriend who’d rejected him. I see this one almost every time I read or view an account about Bundy. Yet when Bundy heard about this “subconscious complex,” he scoffed.

“They [his victims] just fit the general category of being young and attractive,” Bundy told investigator Hugh Aynesworth. Youth and beauty were “absolutely indispensable,” and Bundy preferred college girls. At any rate, he got direct revenge on the woman who’d rejected him, so why target symbolic victims? In addition, during the 1970s, long hair parted in the middle was the fashion for young women, so it’s likely that his victims would have this style. Even so, not all of them did.

3. Bundy was a teen before he discovered that Louise was his mother, not his sister. In fact, says Bundy expert Kevin Sullivan, Bundy learned the truth quite young.

“There apparently was some confusion in the child’s mind for a brief time,” Sullivan says. “However, this occurred when Bundy was either three or four years old. By the time he and his mother Louise left Philadelphia for Washington State when Teddy was around five, he understood that Louise was his mother. When Louise met Johnnie Bundy, he was well aware that Ted was her son. Instead of raising him as a stepson, Johnnie adopted him and gave him the name Bundy. Johnnie and Louise had four children, and all the kids grew up knowing that Ted was their brother.”

Sullivan adds other proof: “I asked Mike McCann if, in his years of dealing with Bill Hagmaier [an FBI Bundy interviewer], did he ever ask him if Bundy talked about this myth, and Mike said that Hagmaier told him Bundy referred to it as ‘BS.’”

4. Bundy was friends with his victim, Laura Ann Aime. This 17-year-old crossed paths with him after leaving a party on Halloween, 1974. Several people who knew Aime claimed that Bundy had hung out with her at Brown’s Café in Lehi, Utah, had called Aime his girlfriend, had said he was going to rape her (perhaps jokingly), and had been introduced by her to her friends.

In Ted Bundy: The Yearly Journal, Sullivan disputes these accounts: “Those folks who claimed he [Bundy] was spending a great deal of time in a little town 30 miles south of Salt Lake City in September 1974, making friends, and getting to know Laura, are in error.”

Sullivan shows, day by day, what kept Bundy occupied once he arrived in Salt Lake City. There was no time for him to have been casually hanging out, particularly not in this town.

"We have a very busy Bundy the first half of the month with his initial move, his return home, his getting his apartment in the shape he wanted it, as well as interactions he had with the law school," Sullivan says. "Are we to believe Bundy arrived in the city and almost immediately started wandering down to a very small town where he decided that he should start spending a great deal of time there making ‘friends’? If we’re to employ normal deductive reasoning and compare the allegations with those things we now know about Ted’s comings and goings, then we must conclude that this story is not true; it [the person they saw] couldn’t have been Bundy.”

5. Bundy picked up singer Debbie Harry (of Blondie fame) in New York in a vehicle prepared for abduction. Harry has claimed that she encountered Bundy in Manhattan during the early 1970s. She searched for a taxi one morning when a man driving a white car pulled over to offer her a lift. She got in, then discovered the car had no window crank or door handle to let her out. (Yet, she did get out, and in a manner that Bundy would have thwarted.) When she saw Bundy’s photo years later, she “knew” he was the guy.

However, Bundy didn’t have a car like this and he wasn’t near Manhattan during this period. Harry knows her story has been debunked, but she says, “I think they’re really wrong because he had escaped and was traveling down the East Coast. I think that nobody has ever really investigated that.”

Actually, his escape was in late 1977, not during the early 1970s.

Psychologist Martin Davies at the University of London examined belief persistence in the face of discrediting evidence. In one experiment, participants who’d generated explanations for an event persisted more robustly in their beliefs after being discredited than those who’d read provided explanations. Even when the quality of the provided explanations was better than the generated ones, Group One's beliefs persisted. Thus, when something personal is at stake, such as ego investment in one's stance, discrediting with facts has little impact.

In addition, Davies discovered, those subjects who rated high in a tendency toward dogmatism showed greater belief persistence, especially when the false belief added consistency or completeness to a narrative. Subjects were asked to evaluate the outcomes of psychological experiments. They were then told the outcomes were fabricated. Those high in dogmatism generated more reasons to support the outcomes. They couldn’t envision how an alternative to their belief about the outcomes could even occur. They’d already made up their minds.

Dogmatic cognitive styles might account for the persistence of popular myths about Bundy, more so if a person has publicly stated them as true. A personal stake, such as social or financial support, can infuse myths with enough force to ignore the facts. If the myth makes sense, it can feel like truth.

References

Davies, M. (1993). Dogmatism and the persistence of discredited beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology, 19(6), 692-699.

Davies, M. (1997). Persistence after evidential discrediting: The impact of generated vs. provided explanations on the likelihood of discredited outcomes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33(6), 561-578.

Leatham, T. Was Blondie’s Debbie Harry really abducted by Ted Bundy? Far Out Magazine. https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/blondie-debbie-harry-ted-bundy/

Sullivan, K. (2020). The Bundy murders: A comprehensive history, 2nd Ed. McFarland.

Sullivan, K. (2022). Ted Bundy: The yearly journal. Wild Blue Press.