Personality

Are There Really Four Personality Types?

A new study is easily misinterpreted.

Posted September 17, 2018

We love to categorize ourselves and others into personality types. Maybe you’re a “Type A.” Or maybe the Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator, versions of which many have taken on Facebook, labels you a “Protector” (ISFJ). But how distinct are these types? Is everyone clearly Type A or Type B, with no one in between? Or do people fall on a spectrum? If there’s a spectrum, are there two clumps with a few people between, or one clump in the middle with a few people at the extremes? Or something else? A paper published today in Nature Human Behavior finds “robust evidence for at least four distinct personality types.” But before you start calling yourself a Carrie, Samantha, Miranda, or Charlotte (or a Vincent, Drama, Turtle, or E), let’s see what they really found.

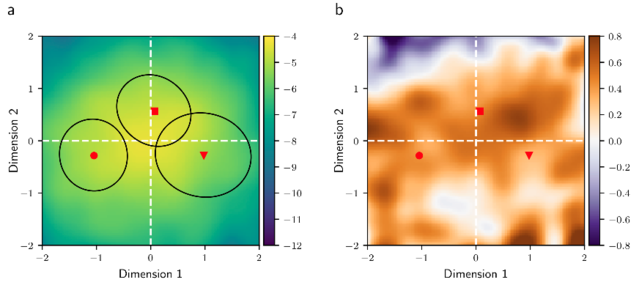

But how clustery are the four clusters? How archetypal are the types? In the population metaphor, are there dense cities surrounded by desert, or is it a land of homogenous suburbs with several barely denser neighborhoods? “We can obtain a more nuanced view addressing the question of the degree of clustering,” the authors write, “by visually exploring densities in suitably defined 2D hyperplanes (Supplementary Fig. 5).” The clusters exist in five dimensions, one for each trait, which is hard to visualize, so they took a two-dimensional slice of this 5D space and presented it in a document supplementary to the paper. Imagine a slice of raisin bread from a loaf.

Unfortunately, the figure doesn’t lend much insight. On the left, you see the raw data. Brighter colors indicate a higher concentration of people. As expected, people are concentrated in the middle of the 2D plot (which is near the middle of the 5D space); more people are near average on each trait than at the extremes. The three black circles purportedly outline three of the four clusters. To my eyes, they are invisible. A land of suburbia. The image on the right shows the difference between the distribution they found and what one would expect from a normal distribution. Here, one can count anywhere from three to 15 clusters, and none of them are centered on the three labeled personality types.

(Also note that the four clusters are in relation to what one would expect from randomized data in which everyone is on a smooth bell curve. Imagine viewing the silhouette of a bell, with the horizontal dimension indicating the score on a trait — ignoring the other four traits for now — and the height indicating number of people with that score. People are concentrated toward the center. These clusters are just smaller lumps on the surface of the bell. So there really is one very prominent personality type: completely average.)

Seeking some intuition about the clumpiness of the personality types, I emailed the authors last week. Martin Gerlach, a physicist at Northwestern University, replied, “I think it is fair to say that they are definitely not well separated.” If there’s no visual way to represent the clumpiness, I asked if maybe he could provide a ratio of the density near the clumps to the density elsewhere. “I am afraid, I cannot put a number on it,” he said. “The major insight from our study is that there is any robust signature about lumps at all.” In the land of suburbs, those slightly denser areas are reliably slightly denser.

(Update: Luis Amaral, one of the paper’s authors, sent some additional data. The population of each cluster is 25-75 percent greater than one would expect from a smooth bell curve. In that calculation, each cluster has a radius of 0.6-0.75 standard deviations — though in reality they don’t have discrete boundaries. More data and further study are required, but by my rough calculations, using the clusters’ locations, radii, and densities, only about 1 percent of people fall into any of the clusters. Before you read the headlines about this study and say, “Oh, there are four personality types? Which one am I?” I’ll tell you: You’re not any of them.)

So although people love finding patterns in the world, typecast carefully. That means not assuming that if someone matches a type in some ways, he will in others. Let’s say someone seems low in openness and conscientiousness. You might assume he is also low in agreeableness, because those three traits cluster together as the “self-centered” type. But the chance that someone low in openness and conscientiousness is also low in agreeableness appears barely more probable than the chance that the person is high in agreeableness. Your assumption could easily lead you astray.

Rather than suggesting that we categorize people, what this study reminds us is that people don’t always fit into the bins we expect.