Dementia

How Can Grandma Play Piano When She Can’t Recall My Name?

Learn why habits and procedures are generally preserved in dementia.

Posted June 29, 2019

In our last article, we discussed how older memories are stored in the cortex, the order layer of the brain. In this week’s article, we will turn to procedural memory—memory for habits as well as physical and mental activities—with a look at why many procedures are preserved in dementia.

Habits, procedures, and skills are dependent upon the basal ganglia

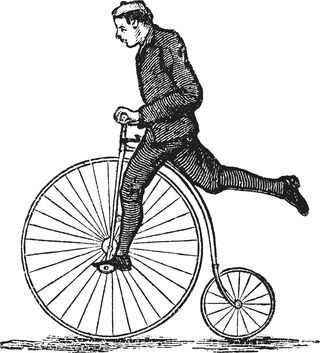

It often appears remarkable that an individual with dementia who does not know where they are or what they had for breakfast that morning may still be able to play the piano or knit a scarf. The reason is that whereas memory for one’s current location or breakfast is stored in the hippocampus, memories for playing piano and knitting are actually stored in other parts of the brain. Procedures, habits, and motor skills, such as playing the piano or riding a bike, are stored deep in the brain in the basal ganglia and cerebellum. Most causes of dementia do not affect these parts of the brain until quite late in the disease.

This discrepancy between remembering skills and procedures versus activities from the day or week before is often confusing for families. We have heard of more than one grandchild who was devastated because their grandparent could not recall their name yet could still play golf, tennis, or a musical instrument without difficulty.

New habits and routines can often be learned through repetition

Because this type of “procedural memory” or “habit learning” is relatively preserved in dementia, many individuals with mild or moderate dementia can learn new (and improve old) procedural skills.

Procedural skills and habits are not learned by verbal instruction. They are learned by doing. Another term for this type of memory is “muscle memory,” and although the learning is actually taking place in the brain, it’s still a helpful way to think about it, as muscles learn only by practice.

Note that your loved one will not be able to remember instructions; they will learn solely by doing. The most effective method is to guide your loved one “hand over hand” without using any words at all. Here are a few examples of activities that could possibly be learned or improved:

- Improve their balance by practicing yoga, tai chi, or similar activity.

- Improve their dancing ability through classes.

- Improve their backhand on the tennis court through lessons.

- Learn to always put their purse, keys, glasses, wallet, and cell phone in the same place each day.

- Learn a new tune on a musical instrument that they have played for years.

- Learn a simple craft, painting, or drawing well enough to enjoy.

- Find their way to the dining room, bedroom, and bathroom when they move to a new location.

- Improve their activities of daily living, such as dressing and brushing their teeth.

Not everyone will be able to improve their activities in this way. Everyone begins with different abilities, skills, and talents, and everyone’s dementia is also different—even if caused by the same disease. If you try to help your loved one improve a skill, and it doesn’t work, don’t be discouraged. They may still be able to improve a different skill, and even if they cannot, you should feel good that you tried!

© Andrew E. Budson, MD, 2019, all rights reserved.

References

Budson AE, O’Connor MK. Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory: What’s Normal, What’s Not, and What to Do About It, New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Budson AE, Solomon PR. Memory Loss, Alzheimer’s Disease, & Dementia: A Practical Guide for Clinicians, 2nd Edition, Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc., 2016.