Psychoanalysis

How To Make A Mountain Out Of A Molehill

The key to understanding the source of our emotional troubles

Posted December 13, 2013

Every so often, I have an “aha!” experience that helps me understand the meaning of a common saying. I’ll be working in session with a patient just doing what I do: listening carefully to try and understand my patient’s inner psychological world and then trying to find a simple way to put that understanding into words. I’ll search my mind for a vivid image, a catchy phrase, an apt metaphor. Not only do I want to convey some understanding, but I want to get their attention. I want to engage them at a deep emotional level so that they will take stock, think, be impacted, and maybe even take away a new idea.

So the other day, I was working with a patient and we were trying to understand why she had overreacted to something. To protect her confidentiality, I won’t tell you the exact issue but you can probably guess the general scenario. Someone takes your parking spot or cuts you off on the freeway. Someone criticizes you or doesn’t follow-through on a commitment they made to you. Attendance at your event, or views on your blog, or tips at your table are down that day. These experiences would bother any of us. But some of us, on some days, in some states of mind, will be more than bothered; we will be terribly hurt, angry, upset, or even enraged. In such states of mind, a minor injury is felt to be a mortal wound. A difference of opinion is felt to be World War III.

So my patient was struggling with her reaction in one of these scenarios and brought it to her session. In this particular case, she already had done some good work on it herself. She knew she had overreacted. That made our work easier, for it wasn’t a question of if she had overreacted but why she had overreacted. And that is a great question for psychoanalysis.

As I found myself putting some words to her question, there it was: that common phrase that I had never thought about from a psychoanalytic perspective. I said to her that what she was really wondering about was why had she made a mountain out of a molehill?

That’s a phrase most Americans will recognize, even though the image is so far removed from our everyday experience. We know mountains, yes, but molehills? Molehills are those pesky little mounds of dirt that moles and gophers leave behind as they make their tunnels just beneath the earth’s surface. I’ve seen a few molehills in real life and I’m no stranger to the film, Caddyshack. But it’s not like molehills are everyday sightings in my life in LA. So after the session was over, I got to thinking about that phrase. I wondered why it has endured and what it conveys about the dynamics of the human mind.

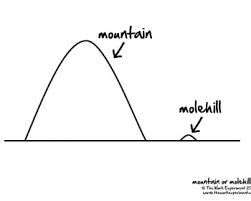

How does a molehill become a mountain? Physically speaking, a molehill becomes a mountain when an animal takes dirt from somewhere and piles it on somewhere else. Psychologically speaking, if we think metaphorically, making a mountain out of a molehill essentially is a massive displacement of psychological dirt from one place to another. We unconsciously dig up dirty issues from one significant area of our lives and pile them on to something far more innocuous. I think this happens because it seems easier to pile a little bit of dirt somewhere else than deal with the psychological mountain itself, intimidating as that often is.

We all have psychological dirt, mess, or trouble in our lives that feels so enormous that we cannot deal with it directly. So, bit by bit, we bury it in the unconscious. Call it suppression, repression, or denial, you get the idea. A psychological shovel is involved.

I like to say that the unconscious is essentially a burial ground for unwanted parts of ourselves—experiences, feelings, thoughts, and impulses—in other words, the dirt of our lives. We bury those parts of ourselves and hope to be done with them. But it doesn’t work. Those unwanted issues have a life of their own. They don’t just die. So when we are tunneling our way through life, they inadvertently and inevitably get disturbed. As our saying of the day tells us, when they can’t be dealt with directly, they get displaced somewhere else. We dump them onto minor issues that (unconsciously) remind us of the deeper trouble. As a result, these minor issues are felt to be bigger than they really are. They have both the emotional intensity that actually belongs to them and the added intensity of those powerful, unwanted issues that we have buried beneath the surface. That’s how a molehill becomes a mountain.

The value of psychoanalysis is that it offers a map to help us navigate the mind’s unconscious tunnels. It can provide an understanding of why we have overreacted, helping us find our way back to the real source of the trouble. The insensitivity of a co-worker or another driver might be linked to an early childhood of neglect or abuse. The criticism of a boss or teacher might be linked to a harsh inner judge who demands absolute perfection. The waning applause might connect with a lack of support in one’s current circumstances or most intimate family relationships.

If we study the mountainous molehills carefully, sometimes we can find where the dirt really comes from. Such insight can put things into better perspective. It can help tell the difference between real molehills and real mountains. With such perspective, life becomes a lot easier to deal with. And, ultimately, that’s what psychoanalysis is all about.

Copyright 2013 Jennifer Kunst, Ph.D.

Like it! Re-post it!