Memory

What Do Psychologists Mean When They Say "Experiment"?

Control groups and control conditions allow for vital comparisons.

Posted August 29, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Control is one of the key features of an experiment.

- This means using control groups or control conditions for comparison.

- The quality of comparison matters—we can't just compare doing something with doing nothing.

What makes an experiment, an experiment?

In the last, first post of this blog, I mentioned that much of research methods is trying to make sure we draw the right conclusions, while also trying very hard not to draw the wrong conclusions. The type of study particularly suited for this is the experiment. Contrary to popular belief, not every study is an experiment—in fact, in psychological research, the term "experiment" is narrowly defined as a study involving both randomisation and control. In this blog post, I want to explain what we mean by control and why it is such an important part of research.

Let’s assume a group of researchers wants to find out how to improve childrens’ working memory in the long term. In fact, we don't need to assume because that's precisely what researchers Henry, Messer, and Nash wanted to find out in their 2013 study. In particular, they want to test whether adaptive "executive-loaded exercises" are effective in training children working memory. "Executive-loaded" means these are exercises that put a cognitive load on the executive function, i.e. the part of the brain that allocates cognitive resources and attention; adaptive means they adjust to the children's skill and get easier or more difficult as the children progress.

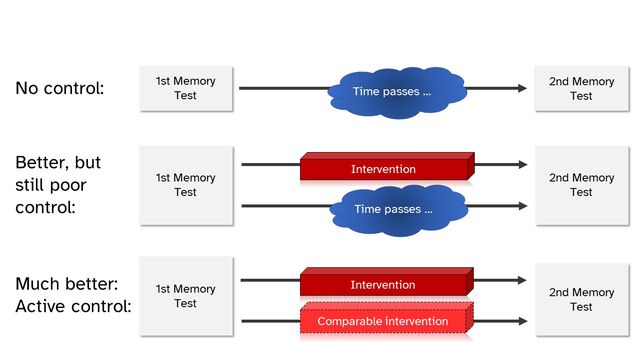

Surely the easiest way for Henry et al. would have been to test the childrens’ working memory to establish a baseline for comparison, then train them with this set of exercises, then test their working memory again, right?

Simple Comparisons Don't Work

Let's assume for a moment that's what they did. In principle, there are three(ish) possible outcomes in such a situation: the second set of tests show that children perform better in the same working memory tests; they perform equally well; or they perform worse. Luckily for the researchers, the tests show an improvement. Would that allow Henry and colleagues to conclude that these exercises helped children to improve their working memory?

Sadly no. As is the case with most of us,1 we continue to learn and improve our skills—and of course, this is particularly true for children. In other words, there is a distinct chance that the children in the study would have improved over time anyway, and the researchers would not be able to say with confidence that any improvement they might have seen is due to their training method.

What the researchers need, therefore, is a way of finding out whether the improvement is (only) due to the passage of time or, at least partially, to them training the children in this method. They need another group of children who don’t get trained in executive-loaded exercises. This helps establish whether any improvement they observe would have happened anyway, or whether it’s a consequence of the intervention (i.e., the training method). If both groups show roughly equivalent1 improvement, it’s unlikely2 that our method made any difference; however, if the comparison group does not improve, and ours does, we are slightly more justified in concluding that method X might have some merit.

We Need Control

In psychological research, such a comparison group is also called a control group as it’s essentially controlling for the passage of time and the change of skills, abilities, opinions, and experiences that go with it. We also refer to the two groups as conditions, as in “Group 1 experiences condition X, group 2 experiences condition Y.”

But simply having a control group isn’t enough. It’s also important how that control group is selected, and what the control group experiences. In the study by Henry et al., the intervention consisted of repeated in-person meetings with an experimenter. But it could also have consisted of children coming into the psychology department with their parents and spending some time with the researcher during training. Or perhaps the researcher(s) paid house visits to the children and their families.

In any of these cases, the children in our intervention group did receive some more attention and interaction from their parents and/or the researcher(s) than they usually would have—and more than the control group, if control just means doing nothing! You may have heard this referred to as the Hawthorne effect, after research at the eponymous production plant which found that workers’ productivity in a factory improved regardless of the actual intervention (e.g., more light, less light) and eventually concluded that it was the existence of the intervention and the resulting increase in attention that improved workers’ productivity.

… But Not Just Any Kind of Control

Whether the original study really showed such an effect is fiercely debated in today’s literature, but that the presence of an intervention alone can have an effect is fairly well established. That’s the reason why we tend to use what’s called “active controls,” that is, control groups or conditions that also get a comparable intervention or experience. And that's exactly what Henry, Messer, and Nash did: In their study, participants were allocated to either the intervention or an “active control”—a different memory training that was similar in time-commitment and involvement by the children.

Still, in some contexts, the Hawthorne effect may be very difficult to mitigate. In their article in the British Medical Journal, Sedgwick and Greenwood (2015) describe a study testing comparing patient-controlled vs. nurse-controlled administration of pain medication to patients with pain from traumatic injuries.

Which patients fare better: Those that are allowed to control dosage and administration of their pain medication, or those that have medication dosages set and administered by nurses? The answer may surprise you! … Or it probably won’t. Patients who have control over their own medication report better pain management and satisfaction.

But is this because pain management was objectively better and more effective, or because participants had a higher degree of control (and autonomy) over their treatment? They conclude that it’s likely both patients and nurses involved in the study may have been affected by the Hawthorne effect, and that even the “gold standard” of empirical research (double-blinding—more on that in an upcoming post) would likely not have made much of a difference.

Control Alone Isn't Enough

Even active control, however, is not enough for a study to be called an experiment. While control groups or control conditions allow us to exclude some potential influences and reasons for our observations, there are still too many potential distractions and disturbances that we need to account for. And, counterintuitively, one of those requirements relies on randomness. But that's a topic for the next post.

References

1 The question of what constitutes „roughly equivalent” is in itself a complex question and is linked to concepts such as statistical significance – yet another topic for another post.

2 Note that while unlikely, it‘s not impossible, and is also related to concepts such as significance.

Henry, L., Messer, D. J. and Nash, G. (2013). Testing for Near and Far Transfer Effects with a Short, Face-to-Face Adaptive Working Memory Training Intervention in Typical Children. Infant and Child Development, 23(1), pp. 84-103. doi: 10.1002/icd.1816

Sedgwick, P., & Greenwood, N. (2015). Understanding the Hawthorne effect. British Medical Journal, 351.