Harm Reduction

How to Judge Harm Reduction's Success

Data shows harm reduction works. Here's how to read it properly.

Posted October 2, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Harm reduction is a policy that aims to reduce the harms of drug use and meets people where they are.

- After modest implementation, it is facing a backlash in some cities across the United States.

- The data and evidence base shows that these sites are effective, but they must be taken into proper context.

- Harm reduction is a critical tool in our fight to reduce overdose deaths.

By Abdullah Shihipar, Alexandria Macmadu, Ph.D., and Brandon Marshall, Ph.D.

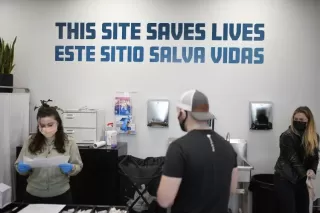

Drug policy in the United States has reached a crossroads. On the one hand, more communities are receptive to harm reduction and are trying new programs to tackle the overdose crisis–from distributing more naloxone to opening overdose prevention centers where people can use drugs under supervision. These programs have emerged due to a growing realization that attempts to criminalize drug use are counterproductive and can lead to further harm. But this attempt to try a different approach has not been without controversy. As quickly as harm reduction and criminal justice alternatives are implemented, a swift backlash can often follow.

In the last two years, this backlash has been most acutely targeted toward cities like San Francisco and Portland, Oregon. Critics claim these initiatives have not reduced overdose deaths, but instead have merely enabled drug use, and with it, lawlessness and public disorder. These criticisms are often sensationalized and can have disastrous consequences for public health policy. In December, the city of San Francisco closed the Tenderloin Center—a center that provided food, referrals to services and housing, and reversed overdoses. Since then, there has been an increase in overdose deaths, amid an ongoing push to arrest people who use drugs.

As researchers who study the overdose crisis, we support harm reduction initiatives precisely because there is a wealth of data suggesting that these programs are effective at reducing overdose deaths, infectious diseases, and other related harms. However, given the complex nature of the overdose crisis, we understand that there may be confusion and misconceptions around the efficacy of these approaches. To properly assess the success of these programs, there are a few things that we want people to keep in mind.

First, we need to consider the primary goal of harm reduction programs. These programs are designed to address health issues like overdose and infectious diseases directly—through the distribution of naloxone, the provision of sterile syringes and works, and the allocation of trained staff to supervise drug use and reverse overdoses at overdose prevention centers. It is useful to think of these programs as you would your local hospital: hospitals are an important part of our healthcare system, yet we do not expect them to solve all of society’s ills. Like hospitals, harm reduction programs can provide needed and lifesaving tools, but they will not solve a city’s housing crisis or other economic problems. Similarly, both harm reduction programs and hospitals can provide critical pathways into treatment for people living with substance use disorder, but only if those treatment programs are accessible, affordable, and provide compassionate care. While neither is a panacea, both harm reduction programs and hospitals provide essential healthcare services and support for those in need.

This brings us to the next point. Given the utility of these programs, we need to next consider their scale and coverage; how many people can be reached through a harm reduction program? Here in Rhode Island, our state health department reports that fewer than 10,000 people per year access harm reduction services. Yet previous work by our team has estimated that approximately 47,000 Rhode Islanders are at risk for overdose. This gap between need and access is why it’s important to continue investing in these programs.

Next, making generalizations about the effectiveness of harm reduction programs by comparing neighborhoods, cities, or entire states is an error that public health researchers call the ecological fallacy. There could be many other factors—such as differences in cities’ drug supplies, housing affordability, and treatment accessibility—that affect neighborhood conditions like public drug use and overdose rates. Instead, we should evaluate harm reduction programs by looking at what happens to people who use them. This is how we know, for example, that 40 percent of people who used an overdose prevention center in Vancouver in one study took up treatment after using the facility. It’s also how we know that the opening of a syringe exchange in Indiana resulted in a sharp drop in new HIV infections. It is these metrics, documented in peer review studies, that give us the confidence to back these programs as effective.

For these metrics to be measured, a key component is time. Harm reduction programs need time to be established and to be evaluated, and rigorously analyzing these data can take a few years. For those who have doubts about the efficacy of the programs, we suggest waiting for the data to be collected and analyzed. In a few years, we will have data from the first overdose prevention centers in New York City and Rhode Island, as these programs are currently being scientifically evaluated for their efficacy.

We also must remember that harm reduction programs are often plugging holes in broken healthcare, treatment, and social services systems. Much like how a hospital treats people who come in with ailments exacerbated by poverty, lack of housing, and so on, harm reduction programs attempt to keep people alive in an extraordinarily challenging time, against the backdrop of a potent and changing drug supply. We don’t blame the hospital for society’s failures, and we shouldn’t put the onus on harm reduction programs either.

The overdose crisis is a tragic and complex problem that will not be solved overnight; it necessitates a broader and deliberate vision of our drug policy and requires deep, empathetic care for our most vulnerable. Addressing broader structural issues that contribute to homelessness, addiction, and overdose will not be easy and will take some time. In the meantime, we should empower harm reduction programs to continue saving lives, rather than place unrealistic expectations upon them.

Alexandria Macmadu, Ph.D., is a presidential postdoctoral fellow at Brown University and is a member of PPHC. Brandon Marshall, Ph.D., is a professor of epidemiology at Brown University and is the founding director of PPHC.