Animal Behavior

Therapy Dogs: The Politicians of Working Dogs

They are highly trained to provide comfort and support to people in need.

Updated July 31, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Therapy dogs work in hospitals, schools, and elsewhere to help people cope with stress, anxiety, and pain.

- Therapy dogs were a hot topic at ISAZ 2023, with researchers presenting findings on how they support clients.

- The question now is how to train personnel to assess dogs for their malleability.

I’m just back from the annual conference of the International Society of Anthrozoology at the University of Edinburgh, where my students and I presented findings from different studies examining the role therapy dogs play in supporting the well-being of university students.

A highlight was reporting findings attesting to the efficacy of “virtual canine comfort modules,” which are comprised of five-minute asynchronous sessions that students accessed from remote locations at times convenient to them. There is no associated fee and no registration or sign-up required to access these virtual modules.

These are important elements of offering low-barrier, easy-access mental health support to students, who are known to be reluctant help-seekers. Undergraduate students often eschew formal services and prefer to deal with stress on their own or downplay their mounting mental health concerns.

Therapy dogs were a hot topic at ISAZ 2023, with researchers from around the globe presenting findings on how they support clients in virtual contexts, via virtual reality canine interventions, and through reading initiatives with high school students.

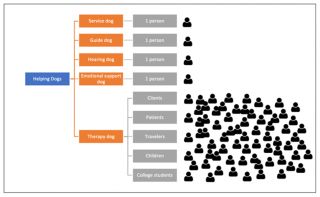

Attending these sessions reminded me of the malleability of therapy dogs (see the graph on the reach of therapy dogs). We ask a lot of them and, under the guidance of their handler, they are able to adapt to both a variety of clients (i.e., children, adolescents, college students, seniors, incarcerated individuals). They also work within and across a variety of settings (i.e., universities, schools, hospitals, prisons, police detachments).

In this regard, therapy dogs differ from other “helping dogs,” which have been positioned as providing highly specific support via a series of trained skills to one individual to help them optimize their potential and live full and integrated lives. As such, we might think of therapy dogs as the politicians of the dog world—ever ready to interact and shake paws with a variety of constituents. This malleability in supporting a variety of clients across a range of contexts is a characteristic that distinguishes therapy dogs from other working dogs.

The question now is how to train personnel who screen and certify therapy dog-handler teams to assess dogs for their malleability. Certainly, a dog's disposition plays a role in guiding this malleability, but so too might handlers facilitate this by introducing dogs to varied people and settings, especially during a dog's formative adolescent phase of development.

This structured and supported public exposure helps prepare and equip future therapy dogs to settle and adjust to new environments, while maintaining a desire to interact with people. As always, the welfare of the dog must be considered front and center throughout this informal public exposure as threats to welfare can arise in uncontrolled, public contexts (e.g., encounters with unsocialized dogs, sudden noises, or crowds).

The field of human-animal interactions, and its subfield of study exploring and examining the effects of canine-assisted interventions, is burgeoning. Therapy dogs are in high demand, and there is a need to understand how to better train them to be adaptable to different clients and settings.

References

Binfet, J. T. & Hartwig, E. (2020). Canine-assisted interventions: A comprehensive guide to credentialing therapy dog teams. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436055

Binfet, J.T., Tardif-Williams, C., Draper, Z. A., Green, F. L. L., Singal, A., Rousseau, C. X., & Roma, R. (2022). Virtual canine comfort: A randomized controlled trial of the effects of a canine-assisted intervention supporting undergraduate wellbeing. Anthrozoos, 35(6), 809–832. https://doi: 10.1080/08927936.2022.2062866

Tardif-Williams, C. Y., Binfet, J. T., Green, F. L. L., Roma, R. P. S., Singal, A., Rousseau, C. X., & Godard, R. J. (2023). When therapy dogs provide virtual comfort: Exploring university students’ insights and perspectives. People and Animals: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 6(1), 1–17. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/paij/vol6/iss1/5