Aphasia, a communication disorder, is a result of injury or damage to the area of the brain that processes language and communication. People with aphasia have difficulty understanding and expressing language. Aphasia can manifest in both spoken and written forms—a person may have a hard time speaking and understanding spoken words. They may also have difficulty with reading and writing words. This can appear after a head injury, stroke, infection, or problems and conditions such as a brain tumor or neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Contents

Aphasia varies widely and depends on the severity of the damage and the area of the brain. It is not an uncommon neurocognitive problem, some 25 to 40 percent of people who survive a stroke experience aphasia. A stroke is a common precursor for aphasia—blood flow to the brain is interrupted, which can result in damage to brain areas that process language. This condition can profoundly affect a person’s quality of life.

Aphasia happens across age brackets. But it is more likely in older adults because of problems like stroke and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and others.

This is a severe type of aphasia, where multiple language areas in the brain have been injured and affected—perhaps by a stroke or brain injury. People with global aphasia have impaired comprehension of single words, full sentences, and whole conversations. They may understand very little that is relayed to them.

This is also called non-fluent or expressive aphasia. The person who suffers from this has a diminished ability to speak spontaneously. They also cannot remember conjunctions and prepositions—"for," "and," "nor," "but," to name a few of many examples. They may understand what is being said to them, and they may be able to understand what they read.

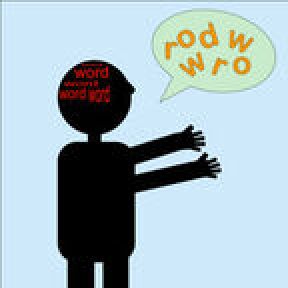

This is also called fluent or receptive aphasia. People who suffer from this can relay connected speech, but they do not understand the meaning of words, may speak nonsense words, speak the wrong words, and have difficulty with written words. They may be unaware of what they are saying.

This is a milder form of expressive aphasia, and people with anomic aphasia cannot find the specific words, especially nouns and verbs, they are thinking about when speaking and writing. They may forget the word apple when looking at an apple.

This type of aphasia is similar to Broca’s, where speech is sparse and effortful, and not spontaneous. It is also similar to Wernicke’s aphasia, where the person is limited in their comprehension of speech.

• Perseverative aphasia: This unintentional repetition of words is also called recurrent perseveration. The conversation has moved on, but the person is still on the previous topic.

• Conductive aphasia: A person with this type of aphasia has halting speech, they are pausing to find the right word, and sometimes they settle on a tangential word.

• Paraphasia: This is also an expressive or receptive type where the person replaces words with wrong and unrelated words.

While aphasia can sometimes improve without treatment, speech and language therapy may be recommended. A speech and language therapist models correct speech and articulation and helps to build language skills.

This approach involves constraining the use of non-verbal communication methods, and encouraging the use of verbal communication; it can promote language recovery.

Various software applications and digital tools are available to aid in language therapy and practice. These can be used under the guidance of a speech therapist or independently.

This is a therapeutic approach that instructs people affected by aphasia and their loved ones in effective communication, both verbal and nonverbal. These strategies encompass various methods like drawing, gesturing, using cues, confirming information, and summarizing discussions to facilitate improved interaction.

A study in Finland found that singing can be an effective treatment. In the study, 50 aphasic subjects joined a choir for a four-month period. The participants had varying degrees of impairment, from mild to severe. This intervention improved everyday communication and the benefits helped at a four-month follow-up.