Resilience

Walking Through a Plague

How history helps inform us about pandemics

Posted May 1, 2020 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

When I talk with patients now, we battle a sense of being stuck in the present. It’s hard to imagine the near future, which just seems like a desert of dreary sameness; it’s hard to remember the recent past, which seems infinitely more long ago than it really is.

Time seems to have stopped or, rather, to have dissolved into a tick-tock routine that we are powerless to change. This frustrates me, since I always counsel patients that positive change is within their grasp (my forthcoming book, in fact, is titled Psychotherapy and Personal Change). But here we are, cemented in this moment, as if even our speech did not take time—343 meters per second—to reach each other.

So, it’s important, I think, to establish some perspective and, if we can’t predict the future in our current position, to at least learn from the past. The past has become more useful than it has been for some time: Normally, we inhabit a culture fixated on the next deal, next date, next anything that satisfies our need for possibility. But as we find ourselves in this endless protracted moment of anxiety tinctured with boredom, we suddenly have time for the past. I mean the real, deep past, not just yesterday’s news or the photos that fall from a drawer now that we fill our days with cleaning house.

There is a website with 60,000 old books, Project Gutenberg, where virtually all the classics are available for free. While it was not made to liberate us from our current stay-at-home navel-gazing, it might as well have been. Same with Eighteenth-Century Collections Online (ECCO)—thousands of titles, most of which I never heard of. With a New York City library card, ECCO is also free. Same with Early English Books Online (EEBO), for books before 1700. In other words, the past is extraordinarily accessible—even if the grocery store is not. After Skyping with patients all day, I wandered through these sites, looking for discussions of how to cope with extremity.

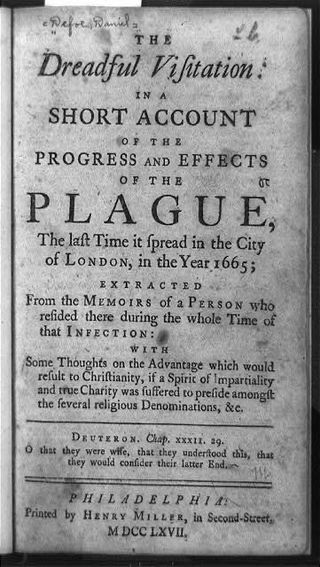

I found some of them. In the 17th and 18th centuries, repeated bouts of plague felled millions, and people reflected in print on the devastation. In these books and pamphlets, I entered a world of antique English (ironically revived through modern technology), where everyone was as scared as we are. There were titles like The mirror or glasse of health necessary and needful for euery person to looke in, that will keep their bodye from the sicknesse and pestilence (1580). Or, some serious notes and suitable considerations upon the present visitation at London wherein is something by way of lamentation, information, expostulation, exhortation, and caution (1665). They make one shudder.

Of course, no one really had a cure. Medicine consisted in medical lore, circulating much like urban myth does today. Except for the utterly credulous, people developed psychological defenses—they compensated, like the blind who cultivate hearing. This is what interested me.

There is useful epistemology in literary history. A lot of comparison has been made to the London Plague of 1665, and I suggest that for sheer psychological acuity—and the first real claim that uncertainty is the only honest response to pandemic—no one beats Daniel Defoe’s fictionalized account in A Journal of the Plague Year (1722).

Defoe’s narrator, H.F., introduces his account by acknowledging that while the incidents he describes are “very near Truth,” it is a fact that “no Man could at such a Time, learn all the Particulars.” To be in the midst of the Plague was to see it incompletely. Later on, when looking into a pit of the piled-up dead, H.F. acknowledges the ineffability of plague phenomena and the inability of language to render them: “[I]t is impossible to say any Thing that is able to give a true Idea of it to those who did not see it, other than this, that it was indeed very, very, very dreadful, and such as no Tongue can express.”

In an eerie anticipation of our own plague, H.F. asserts that the Bills of Mortality “never gave a full Account, by many thousands; the Confusion being such, and the Carts working in the Dark, when they carried the Dead, that in some Places no account at all was kept, but they work’d on.” In example after example, H.F. demonstrates that the only honest response when trying to describe plague is to say you don’t know because can’t know. In a time of plague, you accommodate to uncertainty. You must.

When I read through this old book, the irresolution it depicts was clarifying. It felt like a diagnosis. We are experiencing the same inability to grasp the situation. We don’t know who is still going to get this disease; how long it will persist; how it will permanently alter our lives. Right now, while we must live in uncertainty and accept it, our chronic inability to fathom it produces enormous stress.

As I talk with patients, and they worry about getting the disease, they worry as much about the effect of all this worry. Like H.F., they see an infinite regress into a morass of unanswerable questions. I can’t tell them not to worry. I can’t simply say to focus on the important things, when they can hardly focus at all.

There has been a lot of discussion recently about how, during this pandemic, people’s ability to focus has declined. One of my patients said, “I try to work, but I keep interrupting myself, and then I interrupt the interruption with something else.” I think that lack of sensory stimulation, the effect of sitting at home day after day, turns the mind into a closed box where whatever is there just keeps ramifying. I have told some of my patients about H.F. and how he makes it through the Plague by means of luck and resilience. It’s possible. I can help my patients to elicit luck by developing skills that contribute to resilience.

As we talk, I say “Look, we have vastly more resources than they did. And their first resource was themselves.” The point is to approach our current dilemma by accepting it—in its complexity and uncertainty—and then trying to see how we can live our best lives in this constricted present. We should maintain our connections and feel part of the world, so that we can be there when the world returns. It’s up to the world to return. We can’t make it. But we can be ready for it.

I am taking walks, exercising, practicing yoga and meditation. I am focusing on my family, which is a great source of support. We have to seek support where we can find it. I am journaling and writing more. Creativity has now become smaller scale, but it’s no less real or important. It’s possible and we have to try.