Media

Has Social Media Harmed Teens' Mental Health?

Research refutes claims about the dangers of iPhones and social media.

Posted November 2, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

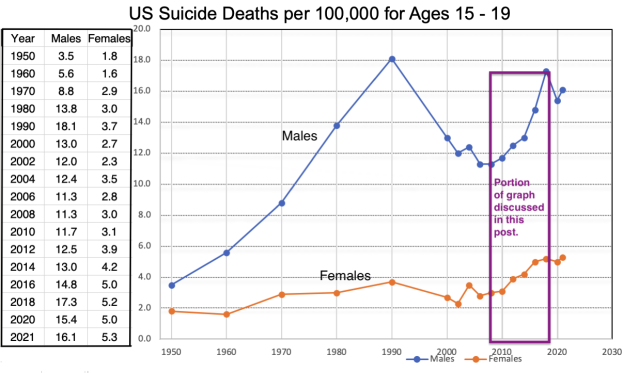

This is the sixth in my series of posts aimed at understanding the causes of the changes in suicide rates among U.S. teenagers from 1950 to the present, which are depicted in the graph below. For summaries of how I explained each portion of the graph--including the difference in rates between boys and girls, the increasing rates from 1950 to 1990, the declining rates from 1990 to 2008, and the increasing rates from 2008 to 2019. (See my most recent previous post.)

My goal in the present post is to examine evidence relevant to the popular theory that teens’ increased use of digital technology, and particularly their increased use of smartphones and social media, is a major cause of their increasing rates of anxiety, depression, and suicides from 2008 to 2019. My conclusion—consistent with the conclusion of the great majority of behavioral scientists who have published research on this question—is that digital technology probably has some negative effects on young people’s well-being (and some positive effects, to be discussed in a future post), but the negative effects are too small and inconsistent to explain the sharp decline in mental well-being over this period.

The research aimed at understanding the relation of teens’ uses of digital technology to their mental health is of three main types: cross-sectional correlational studies, longitudinal correlational studies, and random assignment experiments. I will take each in turn.

Findings From Cross-Sectional Correlational Studies

In these studies, researchers collect data on the amount of time a sample of adolescents spend with digital technology or some specific use of that technology, such as social media, and also data on some aspect of their mental health, such as their level of anxiety or depression, and look for a correlation between the two.

Many dozens of such studies have been conducted, and at least 10 independent reviews of them have been published. Some of the studies show positive correlations between digital technology use and mental well-being, some show negative correlations, and some show no correlation. Overall, the reviews reveal that, taken as a whole, the studies reveal a small negative correlation between measures of digital technology use and indices of mental health. This is true regardless of whether the measure of technology use is total screen time, total time on a smartphone, or time on social media platforms. Most reviewers conclude that the correlation is statistically significant in large samples but too small to be of practical significance. Here are some examples of conclusions from major reviews of the cross-sectional studies:

- In a meta-analysis of 33 separate studies published between 2015 and 2019, Christopher Ferguson and his colleagues (2022) concluded: “On balance, the data fail to support the contention that exposure to screen media generally, or social media and smartphones specifically, is associated with negative mental health symptoms. Specifically, effect sizes were below the threshold of r = .10 used for interpretation of the findings as hypothesis supportive. Given that some methodological limitations are endemic to the field, it remains likely that such small, albeit 'statistically significant' effects are likely to be explained by systematic methodological flaws rather than true effects. This possibility is supported by evidence that those studies which used proper controls generally found lower effect sizes than those which did not.”

- In a review of studies correlating social media use with self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (SITBs), Jacqueline Nesi and her colleagues concluded: “Notably, no evidence emerged for associations between frequency of social media use and SITBs.”

- In a review of many studies linking total use of digital technology with measures of mental health, conducted between 2014 and 2019, Candice Odgers and Michaeline Jensen (2020) concluded that individual studies have generated “a mix of often conflicting small positive, negative and null associations.” and “The most recent and rigorous large‐scale preregistered studies report small associations between the amount of daily digital technology usage and adolescents’ well‐being that do not offer a way of distinguishing cause from effect and, as estimated, are unlikely to be of clinical or practical significance.”

- In another review of studies linking total digital technology use with measures of mental health, Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylki (2019) concluded: “The association we find between digital technology use and adolescent well-being is negative but small, explaining at most 0.4% of the variation in well-being. Taking the broader context of the data into account suggests that these effects are too small to warrant policy change.”

- In an umbrella review (a review of reviews), Amy Orben (2020) concluded: “[T]he association between digital technology use, or social media use in particular, and psychological well-being is—on average—negative but very small.”

- In another umbrella review of 25 reviews that focused specifically on social media use, Patti Valkenbur and colleagues (2022) concluded: “Results showed that most reviews interpreted the associations between social media use and mental health as ‘weak’ or ‘inconsistent.’”

Findings From Longitudinal Correlational Studies

Cross-sectional studies can show positive or negative correlations between digital technology use and indices of mental health but cannot reveal the direction of causality. A small correlation, for example, between social media use and depression could indicate that social media use causes a slight increase in depression or that depression causes a slight increase in social media use (perhaps as a way of dealing with the depression), or that both social media use and depression are promoted by some third (unknown) factor.

One way of trying to establish direction of causation is to conduct longitudinal correlational studies. In these studies, research participants are assessed for their technology use and mental health at two or more points in time. A correlation of high social media use at time 1 with reduce mental health at time 2 suggests that social media use is a cause of decline in mental health. Conversely, a correlation of poor mental health at time 1 with increased social media use at time 2 suggests that reduced mental health may be a cause of increased social media use.

An example of such a study is that conducted by Abigail Bradly and Andrea Howard (2023) with 187 university students as subjects. Each week for 12 weeks the students submitted screenshots of their iPhone “screen time” settings display and completed surveys measuring stress and mood. The results showed no significant correlations over time in either direction. Heavier smartphone use in a given week did not predict end-of-week mood states, and higher stress levels did not predict increases in smartphone use. The researchers concluded, “Our findings contribute to a growing scholarly consensus that time spent on smartphones tells us little about young people’s well-being.”

Another recent example, over a longer period, is a study conducted by Silje Stensbekk and colleagues (2023) with 180 young people who were 10 to 16 years old at the beginning of the study. At four times, over a two-year period, each subject was assessed for anxiety, depression, and amount and type of social media use. The results revealed no significant effects, regardless of gender. No index of social media use predicted future depression or anxiety and no index of depression or anxiety predicted future social media use for either girls or boys.

These are just two of many longitudinal studies that have now been published. In a review of such studies, Samantha Tang and her colleagues (2021) concluded that they revealed either no or very small effects in either direction. In their conclusion, the researchers wrote: “Messages about the negative impact of screen time on the well-being of young people feature frequently in the media, the community, and political discourse. The current review suggests that this discourse may not accurately reflect the available scientific literature and that the magnitude of the effects when they can be measured range from small to very small. It is likely that the degree to which increases in screen time account for the recent rise in mental health problems among young people is negligible.”

Findings From Random-Assignment Experimental Studies

Random-assignment experiments are commonly regarded as ‘the gold standard” of research aimed at showing causation, but, as I will point out, they are seriously flawed when used in research on effects of social media.

Many experiments have now been done in which the subjects (usually college students) are randomly assigned to an experimental group or a control group. The experimental group is asked to reduce their use of digital technology (or some aspect of it) for some period and the control group is not asked to do that. If those in the experimental group show improved mental well-being at the end of the experiment relative to the controls, that is taken as evidence that the technology use was suppressing well-being.

Such studies have shown mixed findings, much like the correlational studies. Perhaps the best example of a study interpreted as evidence for the value of reducing social media is one conducted by Manuela Faulhaber and colleagues (2023) with 230 college undergraduates. The students were randomly assigned either to limit their social media usage to 30 minutes per day or to use social media as usual for two weeks. At the end of the two weeks, those who limited social media showed statistically significant reductions in self-reported anxiety, depression, and loneliness.

This study, taken at face value, would seem to be good evidence that reducing social media use is good for mental health. However, I must note two fundamental problems that apply to all experiments of this type—problems that really negate the value of this approach.

The first problem is the placebo effect. It is well known, from countless studies, that anything that people do or take that they believe will reduce their anxiety or depression in fact does reduce their anxiety or depression, at least for a short period. This is why it is so difficult to prove that drugs for anxiety or depression are effective. The placebo effect is so large that it is difficult for any drug to have an effect more than the placebo. We can assume that subjects in social media experiments are aware of the common belief that social media use has harmful psychological effects, and it even seems likely that such awareness is what led them to volunteer to be in the experiment. With drug studies you can hide from the subjects which ones are getting the drug and which are getting the placebo, but with technology studies the subjects naturally know which group they are in. There is no way to show that an effect of reducing social media is not just a placebo effect.

The second problem is what researchers call the demand effect. Subjects in research experiments are very good at guessing what the research hypothesis is and, consciously or unconsciously, are motivated to prove the hypothesis correct. (I’m sure there are some contrarians motivated to prove the hypothesis wrong, but much research has shown that the contrarians are in the minority.) In the experiments involving reduction in social media the hypothesis is pretty obvious. There is no good way of getting around the demand effect, and the effect may be especially strong in the typical experiments where the subjects are college students and the researchers are professors at that college.

None of the random assignment experiments I found made any attempt to account for the placebo or demand effect or even mentioned them. My own belief is that this makes these experiments worthless. However, even with the boost of the placebo and demand effects, experiments of this type have shown mixed results, with either no or small effects (see review by Orben, 2020).

Conclusion and Further Thoughts

My own conclusion from immersion into the research on the effects of screens, smartphones, and social media is that the research is, on one score, quite conclusive. None of these account for the large recent rise in suicides (or other indices of mental suffering) in teens. The very small effects found in some of the studies have been blown up in the media in ways that augment popular prejudice. It is time for researchers to communicate these findings clearly to the public. Taking smartphones or social media away from kids will not result in a major reversal of their high current rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide.

However, the lack of a meaningful overall effect does not mean there are no problems at all with social media for teens (the same applies to the rest of us). There are both problems and benefits, and these likely play themselves out differently in different people. In a future post, I’ll discuss, qualitatively, the various ways that teens use social media and digital technology more generally, how they benefit from it, and ways that some uses can be harmful. I will suggest that instead of depriving young people of smartphones and social media, we should talk with them about safety rules.

Unfortunately, the societal instinct in recent times is to take away young people’s freedoms whenever we think there are dangers, rather than teach safety. We have done that with the outdoors. Decades ago, we taught children how to be safe outdoors—how to cross streets, what to do if a stranger wants you to get in their car, and the like. Now we ban them from the outdoors, so the only regular way they can get together without adult interference is through social media. And now the hue and cry, from some, is to ban them from social media, leaving them no way to connect with their peers away from adult surveillance and control. Please, let’s not go down that path.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and questions. Psychology Today does not allow comments on this platform, so I have posted this also on a different platform where you can comment. I invite you to comment here.

References

Bradley, A.H., & Howard, A.L. (2023). Stress and Mood Associations With Smartphone Use in University Students: A 12-Week Longitudinal Study. Clinical Psychological Science 11, 921–941

Ferguson, C.J., Kaye, L.K., et al. (2022). Like this meta-analysis: Screen media and mental health. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 53, 205–214.

Faulhaber, M.E., Lee, J.E., & Gentile, D.A. (2023). The Effect of Self-Monitoring Limited Social Media Use on Psychological Well-Being. Technology, Mind, and Behavior https://doi.org/10.1037/tmb0000111

Nesi, J. et al., (2021). Social media use and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 87.

Odgers. C.L., & Jensen, M.R. (2020). Annual Research Review: Adolescent mental health in the digital age: facts, fears, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61, 336-384.

Orben, A. (2020). Teenagers, screens and social media: a narrative review of reviews and key studies. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55, 407–414

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A.K. (2019). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour, 3, 173–182.

Steinsbekk, S., Nesi, J., & Wichstrøm, L. (2023). Social media behaviors and symptoms of anxiety and depression. A four-wave cohort study from age 10–16 years. Computers in Human Behavior 147, 107859

Tang, S., Werner-Seidler, A., et al. (2021). The relationship between screen time and mental health in young people: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review 86, 102021

Valkenburg, P., Meier, A., & Beyens, I. (2022). Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: An umbrella review of the evidence. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 58–68.