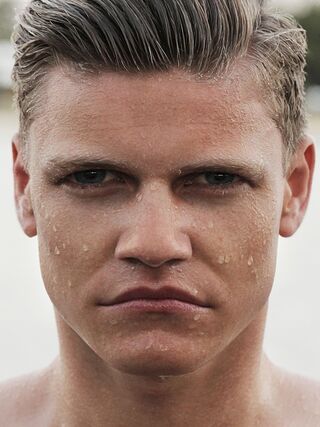

Anger

What’s the Main Problem with Anger Control Techniques?

Managing or suppressing your anger is hardly the same as resolving it.

Posted August 11, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

As peculiar—or paradoxical—as it sounds, the response of anger is a great pseudo-solution for almost every significant emotional disturbance. I say “pseudo” because the immediate positive effects of anger are only temporary, and essentially bogus.

On the surface, anger is an exceptionally powerful way of deflecting from difficulties and upsets that revive old feelings of inadequacy, insecurity, or powerlessness. And frankly, virtually all of us are at times strongly drawn to it because of its unusually fortifying aspects. For example, producing adrenaline during this “fight” reaction literally makes you feel stronger, in addition to secreting the analgesic noradrenaline, which offers you physical comfort not available elsewhere. But viewed from a broader, more existential perspective, your anger doesn’t begin to address the deeper personal issues that provoked it in the first place.

In many previous posts, I’ve discussed anger as a secondary emotion best seen as a core psychological defense against the more distressing emotion(s) that preceded it. Albeit unconsciously, it’s employed to assuage such painful feelings as hurt, disappointment, guilt, shame, anxiety, and humiliation that may have afflicted us since childhood. And it accomplishes this remarkable feat by projecting these bad feelings onto others who—by dint of disagreement, criticism, or out-and-out rejection—have reactivated in us (most often unintentionally) old doubts or misgivings we’ve never fully overcome.

Firmly rooted in the language of blame—or counter-blame—anger works as follows:

- “I’m not worthy” is conveniently translated into “You’re not worthy.”

- “I’m inept or incompetent” becomes “It’s not me who’s incompetent; it’s you.”

- “I can’t do anything right” transforms into “You can’t do anything right.”

Get the picture? This list could go on indefinitely and include such it’s-not-me-but-you” items. “I’m inferior” “I’m defective (broken or flawed).” “I don’t measure up.” “I’m stupid, or not smart enough.” “I’m hopeless, unacceptable, a loser, not likable, or not wanted.” “I’m not deserving of love or respect.” I’m a mistake, contemptible, a bad person, or fraud.” or “I’m ugly, too fat, or too thin.”

Perhaps the single, most common, and inclusive negative belief that plagues so many of us is “I’m not good enough,” or even worse—and more discouraging—“I can’t be good enough” (talk about self-defeating beliefs).

The problem with most anger management techniques is that they focus on here-and-now methods for regaining lost emotional equilibrium. They’re about controlling or limiting, the expression of anger rather than eradicating it through helping to convince us that it’s no longer needed: That we no longer require this pivotal defensive emotion to compensate for unfavorable ways that, deep down, we continue to view ourselves.

Because these techniques aren’t specifically designed to get to the source of our anger, and so help us repair chronic self-image deficits, our covert, long-standing belief that our anger is not only warranted but essential in warding off (perceived) attacks on our adequacy remains intact.

Here are some self-help anger management strategies that, because they don’t—and can’t—go far enough, may ameliorate your current anger without in any way conquering it. In other words, the anger will only return later on:

- Various methods of calming yourself, such as deep diaphragmatic breathing, muscle relaxation, yoga, meditation, and visualizing a comforting scene while engaging as many of your senses as possible

- Strenuous exercising to act out, or diminish, the adrenaline surge emanating from your impulsive hostile reaction to whoever or whatever pushed your buttons

- Taking a timeout to reflect on the event and strive to understand it from a less personal, less accusatory viewpoint

- Bringing humor to the rescue by reevaluating the situation from a less serious, more ludicrous, or even absurdist perspective

- Becoming more solution- vs. problem-oriented

- Developing better assertiveness skills—for if you can’t peacefully air out your frustrations so consequently must hold them in, over time their build-up will lead you to lose your cool even worse

- Cultivating more empathy toward the other person, scrupulously considering whether they really intended to offend you (and if they did, consider that beforehand they may have felt offended, or put down, by you)

- Ventilating to someone you trust, someone who you feel understands you (and in a pinch, even your dog or cat might fit the bill here)

- As much as tenable, staying away from people and situations that in the past have routinely left you feeling tense and upset

What’s missing from all these techniques is the awareness that in situations regularly functioning as anger triggers, such reactive anger has become part of your personality—or a "sub-personality" of its own. It’s a go-to defense that through long-term repetition has taken on self-righteous independence, seriously undermining your ability to control it. Certainly, the techniques delineated above can assist you in lessening its strength on a case-by-case basis. But by themselves, they can’t uproot a defense routinely employed for years (if not decades).

What methodology, then, would enable you to rid yourself of—as opposed to merely camouflaging—old, outdated anger?

I’ve discussed this challenging difficulty in many of my earlier posts on anger. Here, I’ll just pinpoint what’s involved in this endeavor and provide references to my writings in which I focus much more on procedures designed to help you get to the other side of anger once instrumental in not having to feel devastated by another’s criticism, refusal, or repudiation.

To the degree that you’ve adopted anger to conceal troubling insecurities or a fragile ego, it will hang around until those insecurities are revisited—and at last, resolved. Because you’ve yet to become sufficiently self-validating, and so attribute more authority to others than to yourself, you’ve remained highly vulnerable to “defaulting” to this so-destructive emotion in times of stress (especially interpersonal stress).

This is to say that the way to end reactive anger for good is to become unconditionally self-accepting. And that doesn’t oblige you to eliminate all your failings or shortcomings but to see them as no longer signifying you’re not good enough. If you’re able to re-appraise yourself as the older, more resourceful person you are today if you can see yourself with greater clarity, understanding, and compassion, another’s presumably negative assessment of you—which might merely represent their own projection—will no longer constitute a threat to your positive self-regard. But if not, you’ll feel compelled to verbally (hopefully, not physically!) defend yourself through fighting off feelings of indignity through asserting moral superiority over your supposed attacker.

Consider the controversial title of the book What You Think of Me Is None of My Business (T. Cole-Whittaker, 1988). In other words, another’s “verdict” of you may well relate far more to themselves than to you. Don’t ever forget that it’s only when your emotional poise is safeguarded by the genuine belief that you’re fundamentally okay that you can approach immunity from others’ negative (or competitive) assumptions and ideas about you. And if you have acted wrongfully toward them, you can, introspectively, explore what misbehavior you might wish to work on. Moreover, once you’ve arrived at unconditional self-acceptance, you can apologize to them without somehow feeling debased.

Like everyone else, as long as you’re alive you’ll remain a work in progress. You don’t need to feel bad about yourself just because you did something stupid or selfish. We can all act boneheaded, inconsiderate, or insensitive at times, which is why it’s so valuable to say to yourself that at any particular moment your behavior was the best you could do—while, of course, pledging to do better in the future.

In my very first Psychology Today post on anger (07/11/08), I made the point that “if we can’t comfort ourselves through self-validation, we’ll need to do so through invalidating others.” And my most recent post on this subject, “How to Talk to—and Tame—Your Outdated Defenses” (07/07/20), should assist you, either through self-therapy or working with an experienced professional, in learning how to feel relatively “inoculated” from the possible put-downs of others.

To conclude, anger management techniques are all about coping with anger. But ironically, anger is itself a coping response, enabling us to feel less powerless or overwhelmed in the face of something that feels threatening. Although very few people appreciate this, one’s proclivities toward anger are best viewed as a coping strategy unconsciously planned to disarm, denigrate, or intimidate “the enemy.” Regrettably, however, whenever you lose your temper, it’s you who is your enemy, and maybe more so than the person you’re in conflict with.

Might this be a good time for you to “trade-in” whatever your angry methods of coping are and set about repairing deficits in your self-image—which in time should render such defenses redundant?

© 2020 Leon F. Seltzer, Ph.D. All Rights Reserved.

References

In my clinical experience, the most effective ways I’ve found to help people with longstanding anger problems is through IFS (Internal Family Systems Therapy) and EMDR. Most of my own articles below, closely complementary to this one, refer to these powerful “inner child” procedures as they’ve assisted me in helping clients move beyond defensive anger.

Earley, J. (2009). Self-therapy: A step-by-step guide to creating wholeness and healing your inner child using IFS, a new, cutting-edge psychotherapy, 2nd ed. Larkspur, CA: Pattern System Books.

Parnell, L. (1997). Transforming trauma: EMDR. New York: Norton & Co.

Schwartz, R. (2001). Introduction to the Internal Family Systems Model. Oak Park, IL: Trailheads Publications.

Seltzer, L. F. (2008, Jul 11). What your anger may be hiding. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/200807/what-…

Seltzer, L. F. (2008, Oct 04). The power to be vulnerable (Part 1 of 3) https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/200810/the-p…

Seltzer, L. F. (2013, Jun 14). Anger: How we transfer feelings of guilt, hurt, and fear. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201306/anger…

Seltzer, L. F. (2013, Sept 11). Surprise! Your defenses can make you MORE vulnerable. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201309/surpr…

Seltzer, L. F. (2016, Feb 23). Anger: When adults act like children—and why. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201602/anger…

Seltzer, L. F. (2017, July 19). How and why you compromise your integrity: Internal family systems therapy can free you from self-sabotaging defenses. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201707/how-a…

Seltzer, L. F. (2018, Mar 07). Feeling vulnerable? No problem—Just get angry. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201803/feeli…

Seltzer, L. F. (2018, May 30). The internal blame game: How you’re at war with yourself. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201805/the-i…

Seltzer, L. F. (2018, Jul 11). The force of your anger is tied to the source of your anger. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/201807/the-f…

Seltzer, L. F. (2020, 07/06). How to talk to—and tame—Your outdated defenses. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evolution-the-self/202007/how-t…