Disaster Psychology

How Mental Health Shapes Recovery After a Disaster

A new study finds links between pre-disaster mental health and recovery.

Posted July 1, 2021 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

Key points

- Survivors of natural disasters are at risk for mental health issues such as depression, anxiety and PTSD.

- People with mental illnesses are more likely to experience posttraumatic stress after a disaster.

- Individuals with mental illnesses and vulnerable populations may be at increased risk following COVID-19.

When disaster strikes, people’s lives are changed in unexpected and unprecedented ways. Natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods, man-made disasters such as terrorist attacks and chemical warfare, and public health disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic all cause individuals to suffer in a myriad of ways for which they are often unprepared.

Recovery from disaster is an ongoing, complex, and highly individual process that demands an immense amount of effort from affected individuals. Disaster victims often find themselves having to work hard to restore their mental health, and in some cases, to rebuild their entire lives.

When Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005, nobody could have predicted the immense scale of its effects. The disaster led to 1,833 deaths, destroyed homes and businesses, and caused an estimated 125 billion dollars in overall damages (EM-DAT, 2021). The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina affected millions of people in different ways, most notably the individuals and families who lived in the disaster zone and survived. These survivors suffered an array of hardships: many lacked adequate access to resources such as food, water, and medication; needed to relocate; worried for the safety of themselves and their families; and/or experienced the death of a loved one.

Due to the stress and trauma they experience, survivors of natural disasters are at an acute risk for a host of mental health issues: Depression, substance use disorder, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder are all commonly reported by disaster victims (Goldmann and Galea, 2014). In addition, survivors often experience posttraumatic stress symptoms without meeting the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, and these symptoms can persist for years after the disaster.

Researchers have frequently studied the progression of mental health outcomes in survivors of natural disasters and other traumatic events. However, since the onset of these disasters is often unpredictable, researchers almost never have information regarding survivors’ mental health and wellbeing before disaster struck. This is incredibly important information – as we have all recently discovered, how we were doing before COVID-19 hit made a real difference to how well (or badly) we were able to adapt to it.

Using Predisaster Information to Understand Reactions to Hurricane Katrina

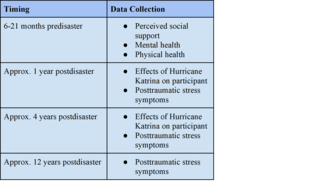

A multi-institutional research team did have unique access to information on participants’ mental health and wellbeing both before and after Hurricane Katrina. Sarah R. Lowe at the Yale School of Public Health and her colleagues at Harvard University and the University of Massachusetts Boston studied participants who were originally recruited from New Orleans for the Opening Doors Study, an educational intervention study targeting low-income parents at community colleges across the country. Within the two years leading up to Hurricane Katrina, these participants had taken surveys regarding their perceived social support, mental health, and physical health conditions. After the hurricane hit, the research team followed up with them.

Because this group of participants had been recruited from New Orleans, they were greatly affected by Hurricane Katrina. The participants were also predominantly low-income, Black, and unmarried mothers. Females, members of minority groups, and individuals with a low socioeconomic status are at a greater risk for posttraumatic stress symptoms (Goldmann and Galea, 2014). As with the COVID-19 pandemic, these populations were hit hard; they felt the effects of the disaster most intensely (Fussel et al., 2010; Zoraster, 2010).

Participants were interviewed one year, four years, and twelve years after the hurricane so that their levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms could be assessed over time. They were also surveyed on the ways in which they had been impacted by the hurricane: housing damage, loss of loved ones, lack of necessities, and other hardships.

Disaster Survivors with Mental Illness Are at Risk for Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

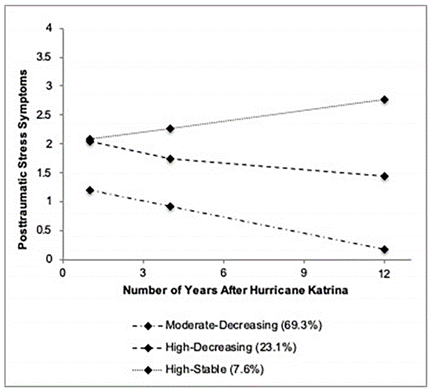

Lowe and colleagues analyzed the posttraumatic stress symptoms trajectories of low-income women in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina using data from the RISK study. In this case, a posttraumatic stress symptoms trajectory describes how a participant’s level of posttraumatic stress symptoms changed over time during the 12 years following the disaster.

Three main trajectories, or pathways, of posttraumatic stress symptoms were detected. The majority of participants experienced moderate symptoms that decreased over time as they recovered from the trauma of the hurricane. In addition, about a quarter of participants experienced severe symptoms that decreased over time. Still other participants endured severe symptoms that remained chronic throughout the 12-year duration of the study (Lowe et al., 2020). The researchers examined whether any of the factors included in the original survey of participants — perceived social support, mental illness, and physical health conditions — could be used to predict which posttraumatic stress symptoms trajectory an individual followed after the hurricane.

The researchers found that lower perceived social support, existence of mental illness, and physical health issues were all correlated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms over time.

However, the impact of perceived social support and physical health could not be discerned once the researchers controlled for disaster exposure. This means that the impact of perceived social support and physical health on posttraumatic stress symptoms could be explained by the ways in which individuals were impacted by the hurricane; participants with lower levels of perceived social support and/or preexisting physical health issues were harmed to a greater degree. This is likely because individuals with lower levels of social support did not have help acquiring essential resources after the hurricane, and individuals with physical health issues were more likely to experience a lack of necessary medicine or medical care.

Once the researchers had adjusted for these other factors, the only predisaster predictor of posttraumatic stress symptoms trajectory that remained was preexisting mental illness. Based on the original survey they had taken prior to the hurricane, researchers could determine whether or not participants were likely to suffer from mental health issues. Those who suffered from mental illness before Hurricane Katrina were more likely to experience chronic posttraumatic stress symptoms in the aftermath of the hurricane (Lowe et al., 2020). In other words, individuals with mental illness were at risk of experiencing high levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms that remained high even 12 years after the onset of Hurricane Katrina.

We Need to Support Vulnerable Populations

The results of this study highlight the need to support individuals with preexisting mental illness and physical health problems in the aftermath of natural disasters. The researchers give the following suggestions for reducing the impact of disasters on these vulnerable groups:

- Healthcare providers should ensure that patients have plans in place for timely evacuation and means to stay connected with close friends and family members should a disaster occur.

- Healthcare providers should encourage patients to have a backup supply of necessary medications.

- Those providing postdisaster assistance should be sure to have adequate supplies of medication for common mental and physical health conditions, in addition to other life-sustaining resources.

Possible Implications for COVID-19

The findings from this study have vast implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. With social distancing guidelines easing and vaccines being distributed, and infection and death rates decreasing in highly vaccinated countries, we would all like to think that the worst part of the pandemic is over. However, even as the heart of the disaster may seem to have passed, the national and global recovery work is only getting started.

Experts predict a long-term mental health crisis, with 4 in 10 adults in the U.S. having reported anxiety or depressive disorder in early 2021, compared to 1 in 10 adults who reported these symptoms in the first half of 2019 (Panchal et al., 2021). In addition, pandemic-related unemployment and school closures have had a large-scale impact on global poverty and education. We cannot know how society will remain affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 10 years, but we can take informed action to support the people who are most in need.

Based on the findings from the Hurricane Katrina study, here are some possible implications for our response, as a society, to the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Individuals with preexisting mental illness are more likely to experience chronic posttraumatic stress symptoms after a disaster. It is important that we continue to provide mental health care to those who received it before the pandemic and to make it available for those who would like to begin receiving it. This could include providing information about health insurance options and mental health care, extending university mental health care into the summer break, and making online mental health care available to people in all locations.

- Lowe et al. noted that members of minority groups and individuals with a low socioeconomic status are at a greater risk for posttraumatic stress symptoms following a traumatic event. Likewise, minorities and those living in counties with lower socioeconomic status have lower rates of COVID-19 vaccination (Ndugga et al., 2021; Barry et al., 2021). Vaccine providers and public health organizations should make sure to provide these vulnerable populations with information about how to access the vaccine and continue running public education campaigns to increase knowledge of and confidence in the vaccine.

- Lowe et al. highlighted the need to support vulnerable populations in recovery from a disaster. Public health organizations and governments should continue to monitor the ongoing effect of the pandemic on unemployment, poverty, and education, and should offer assistance to those who have been most intensely affected.

Kendall Ertel, an undergraduate student at Yale University, and Reuma Gadassi Polack, postdoctoral fellow at Yale University, contributed to this post.

References

Barry, V. et al. (2021). Patterns in COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage, by Social Vulnerability and Urbanicity — United States, December 14, 2020–May 1, 2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7022e1.htm

EM-DAT: The International Disaster Database. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters; 2021 [cited 2021 June 1]. Available from: https://www.emdat.be/

Fussell, E., Sastry, N., & Vanlandingham, M. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status, and return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Population and environment, 31(1-3), 20–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-009-0092-2

Goldmann, E. & Galea, S. (2014). Mental health consequences of disasters. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 169-183. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435

Kronenberg, M. E., Hansel, T. C., Brennan, A. M., Osofsky, H. J., Osofsky, J. D., & Lawrason, B. (2010). Children of Katrina: Lessons learned about postdisaster symptoms and recovery patterns. Child development, 81(4), 1241–1259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01465.x

Lowe, S. R., Rakre, E., J., Waters, M., C., & Rhodes, J. E. (2020). Predisaster predictors of posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories: An analysis of low-income women in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. PLoS ONE, 15(10): e0240038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240038

Ndugga, N., Pham, O., Hill, L., Artiga, S., & Parker, N. Latest data on COVID-19 vaccinations by race/ethnicity. KFF, June 23, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-cov…. Accessed June 27th, 2021.

Panchal, N., Kamal, R., Cox, C., & Garfield, R. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. KFF, Feb. 10, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-o…. Accessed June 27th, 2021.

Zoraster, R. M. (2010). Vulnerable populations: Hurricane Katrina as a case study. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 25(1), 74-48. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00007718