Media

Exposure to Media Violence and Emotional Desensitization

What are the long-term consequences to children and adolescents?

Posted May 6, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Are we—especially our children, adolescents, and young adults—becoming desensitized to hatred, intolerance, and violence depicted on social media? The question posed is rhetorical since my personal and professional assumptions confidently suggest that most would agree that it does, at least to some extent. This is not necessarily surprising or “new news,” but it is disheartening nonetheless and therefore worthy of a healthy dialogue. I have expressed my own thoughts as to why we are witnessing so many mass school shootings and other acts of irreprehensible violence, which I explained in an earlier 2018 publication, "Mass Shooters: A Unique Criminological Explanation."

However, today's focus is more about raising awareness in the hopes of generating a national dialogue leading to positive change. Nearly every single day, we, as a global society, are exposed to what seems like to a constant barrage of violence, negativity, intolerance, and hatred in one form or another on the major news networks, and especially on social media.

Remember when social media was first introduced to the world? Social media began as a way for all of us to reconnect with old friends, and we looked forward to sharing pictures of our families and friends, our travels, and our personal and professional accomplishments. Good times, for sure. That still occurs, but it seems to be occurring with far less frequency. Social media, especially in recent years, can appear as if it's largely become a central hub for spewing hate, intolerance, and in many cases, depicting "real-life" acts of graphic violence and aggression indicative of a total disregard for human life.

A 2016 New York Times article summed it up best. A killer seeks out a nightclub, a church, an airport, a courthouse, a school, a college campus. The number of possible targeted locations is endless. Someone is shot on video, sometimes by the police, and protesters fill the streets. The accused are immediately deemed guilty by the court of social media even though accurate information is scarce at best. A terrorist attack is carried out in France, America, Turkey, Bangladesh, Lebanon, Tunisia, Nigeria, and then claimed and celebrated by another radical, extremist terror group of domestic or foreign origin. Our phones constantly vibrate with breaking news alerts. The cable news captions read “breaking news” in red as the powerful words scroll across the bottom of our TV screens and rapidly infiltrate social media. In response, rumors and misinformation abound. The comments erupt on Twitter, Facebook, and other social media sites. It is a choreographed pattern that has become commonplace while some of us, but not all, try to discern what is real and what is fake news.

How did we get here and why have we become so vocal in openly sharing our political, social, religious, and personal beliefs without regard for its potential impact on the feelings and emotions of others? What happened to that thing we once called empathy? Why do we judge the actions of a few and project those thoughts on the many? Why do we stereotype an entire group of people based on the actions of a few crazed, rogue, or extremist radicals?

Lately, largely in response to the above, I find myself constantly reminiscing about my own childhood. Of course, there were acts of violence. Of course, there were child abductions, murders, global conflicts, etc., but they did not seem to consume every waking hour of our daily lives. We rode our bikes to visit our friends, we played outside, and we spent hours together in our bedrooms or at a local park listening to music. We took long drives in our cars blasting the music with our windows down, and for the most part, life seemed to be more relaxing, less stressful, and less complicated.

Was life truly better back then or am I simply being naïve and gullible? Maybe I am missing something or for some reason; maybe I blocked out negative experiences from my childhood, but as I remember it, we had some good times.

Last week, I received an email from my children’s high school principal announcing a mandatory ALICE training. ALICE is an acronym for “Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, and Evacuate,” in reference to mandatory mass school shooting drills, which occur quite frequently. School shootings do occur and preventative measures to combat a potential incident are absolutely necessary because that is the reality of the world we live in. I am not ignorant of that fact. And yes, I do realize that children who were raised in the early age of nuclear weapons had to participate in “duck and cover” drills; however, my position is that today’s children, adolescents, and young adults are being exposed to too much violence and negativity to the point where another school shooting simply becomes another school shooting without evoking the emotions we would expect in a kid raised in the 1970s, 80s, or 90s.

Tackling this issue would require a multifaceted approach, but what I am most concerned about is how our emotions to acts of violence have become normalized and far from shocking and surreal. What happened to empathy, tolerance, and respecting our differences?

A few weeks ago, one of my young relatives, 17-year-old Jillian, a high school junior from New Jersey, published a poem for her language arts class that was intended to be “reflective” of her hopes and desires of living in a world where happiness, peace, and harmony are abundant. The poem depicts her deep desire in wanting to help others, something that many of us, especially those of us in the so-called “helping professions,” like myself, can easily relate to since it is that very passion that often sets us on the path to our respective careers. She acknowledged that “hoping” without action will not create change in the world, which is something that we can all agree on. We need to stop responding with the all-too-familiar “prayers and positive thoughts to those impacted” types of comments to tragedies that have resulted in little to no action, even though our leaders on both sides of the political spectrum have repeatedly “promised” to create change.

Jillian’s words spoke to me and made me think about how it must feel growing up in a world in which you are exposed to endless stories, pictures, and videos depicting violence, intolerance, and hatred towards others who we perceive to be different and therefore, less worthy because they do not share our personal beliefs and values. Jillian granted me permission to repost her poem which she aptly titled, “I Hope,” which is an emotional plea for change in the world.

I am just an optimistic girl who hopes,

I wonder if I could make a change,

I hear about wars in other countries,

I see animals that do not have a place to call home,

I want to make things better but,

I am just an optimistic girl who hopes

I pretend everything is okay,

I feel sad when I cannot fix problems that hurt others,

I touch people’s hurts and try to make them forget,

I worry when it does not work,

I cry when I cannot help but,

I am just an optimistic girl who hopes

I understand that the world is not perfect,

I say we can change that,

I dream, one day we will all be happy,

I try to help in any small way I can,

I hope we can change the world for good, but

I am just an optimistic girl who hopes

The American Academy of Pediatrics and other reputable organizations have consistently found that exposure to violence at high levels and across multiple contexts has been linked with emotional desensitization, indicated by low levels of internalizing symptoms; the long-term consequences of such desensitization are unknown, but I believe that we can surmise where this is going.

For example, last week, I mentioned to my university students that there had been another campus shooting, which occurred in North Carolina, hoping to start a healthy, productive dialogue about such acts of violence, but the news did not seem to spark any interest, which only confirmed my thoughts that we are becoming desensitized and that is troubling. I thought to myself, "Wow, another shooting—and it is not worthy of an intellectual discussion or debate?"

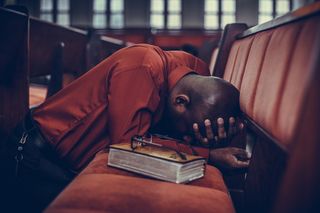

The short-term consequences are readily apparent, at least in my experience as a university professor and father of two teen boys. Depression, anxiety, and other emotional disorders, including suicide, are increasing among adolescents, school lockdowns occur with greater frequency, and the fear of what might happen when we go to church, a restaurant, school, a concert, or any event or venue for that matter can be emotionally destabilizing, leading to a sense of vulnerability and powerlessness that leads us to actively search for all the entry and exit points and remain hypervigilant in the event that something should occur.

We need to delve deeper into the potential ramifications of exposure to too much "real-life" hatred, intolerance, and violence. While there have been numerous studies over the decades focusing on violence on TV, in the movies, and in video games and their potential influence on aggression and violence in children, those are not real-life. I am not discounting that such violence could influence or contribute to real-life violence, but I am most concerned about children and adolescents witnessing horrific incidents in real-time with mostly little to no censorship of the horrific and quite graphic fatalities, severe injuries, or the traumatic reactions to those who witnessed the events firsthand. I am not in favor of censorship because I believe that could it lead down a slippery slope to too much governmental oversight, but on the other hand, I feel strongly that our children are witnessing the worst of what humankind is capable of doing. That should concern all of us.