Dementia

Body Ownership and the Spirit of Capitalism

Bodies and memories aren't property.

Posted July 17, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- The culture of capitalism has influenced how people think about bodies and memories.

- Body ownership experiments reveal that people's concepts of their bodies can quickly be changed.

- Thinking of a body as property hides people's dependence on other organisms and creates a false sense of a self apart from the body.

I participate in capitalism, sometimes enthusiastically, so I won’t be a hypocrite and condemn this economic system. But I do want to show how cultural economic metaphors have shaped many people’s understandings of their bodies and memories. In 1905, German social scientist Max Weber argued in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism that ideas from Calvinist Protestantism helped capitalism to develop (Weber). Central to capitalism are the notions of private property and individual responsibility: one owns whatever one can earn just as one owns oneself.

Long before modern capitalism existed, the idea of owning one’s body was incorporated into any language that derives from Latin roots. The modern words “property,” “proper,” and “appropriate,” which have come to English through French, can be traced to the Latin words “proprius” (“one’s own”) and “proprium” (property), which are themselves related (“Proper”). In French, depending on context, the word “propre” can mean either “one’s own” or “clean” (“Propre”). The scientific term for sensing bodily position and movement, “proprioception,” also comes from the Latin “proprius” (Kandel et al. 480). Culturally, these relationships among words imply links among the ideas of selfhood, ownership, responsibility, and good behavior. What you own reflects who you are, and you should take good care of it. Through language and culture, these principles have been extended to human bodies, which are understood as owned by human selves.

In neuroscience, body ownership experiments have produced valuable knowledge, some of which challenges the notion that bodies are owned. Neuroscientist Henrik H. Ehrsson and his colleagues have shown that within 10 seconds, many people can be convinced that a rubber hand belongs to their body if their actual hand is hidden from view, the rubber hand is placed where the real hand would normally be, and the real hand and rubber hand are stroked in sync (Ehrsson 180). In the lab, Ehrsson’s group has repeatedly induced not just this “rubber hand illusion” but a “full body illusion” in which cameras and head-mounted displays cause a participant to see a mannequin when s/he looks down at his or her torso (Ehrsson 190-91). If the mannequin and the person’s body move synchronously, the participant begins to feel that the mannequin is him or her (Ehrsson 190-91). Spatially and temporally, these illusions have limits: the stroking or moving of false and real hands or bodies must be nearly synchronous, and the false hand or body must lie close to where the real one would ordinarily be (Ehrsson 182-83). Nevertheless, Ehrsson’s group’s experiments show how fast people can be persuaded that they "own" a mannequin torso or a rubber hand.

Body illusion experiments reveal the plasticity of a person’s body image, which “can be profoundly modified with just a few simple tricks” (Ramachandran & Blakeslee 62). Rubber hand illusion experiments challenge the Western notion that a human being is a “single, unified self in charge of [his or her] destiny” (Ramachandran & Blakeslee 83). In the past decades, increasing knowledge of gut flora has challenged the concept of an intact, independent self. The bodies people supposedly own depend on microorganisms living within them. Biologically, no human being is independent.

The concept of body ownership, furthermore, can’t easily be reconciled with the current scientific paradigm that human minds and bodies are inseparable. What self, apart from a human body, exists to claim it as property? Can a body own itself, complete with myriad microorganisms, or a baby growing in its womb?

When it comes to mental functions that bodies enable, the idea of ownership produces even greater distortions. Metaphors of storage, theft, or even loss of memories misrepresent the way memory works. At this year’s conference of the International Society for the Study of Narrative, literary scholar Avril Tynan argued that the concept of transformation describes the changes caused by dementia better than the metaphor of loss (Tynan). Tynan drew on the work of philosopher Havi Carel, who studies the phenomenology (inner, conscious experience) of illness (Carel). In an interpretation of Anne Bragance’s novel, La Reine nue (The Naked Queen, 2004), Tynan pointed out how the central, matriarchal character’s dementia altered a whole family’s relationships. From an individual perspective, loss may seem like a reasonable way to describe the changes dementia brings, but transformation takes into account all the family members and friends whose lives are altered by one person’s dementia. Seeing dementia as a transformation, Tynan proposed, could lead to a different social view and improved care for demented people.

Like the concept of body ownership, the idea of memory loss has roots in the possession of material property. As scientific understanding of memory has progressed, the metaphor that represents memories through the storage of physical goods, as in a warehouse, has become less and less apt. In the late 19th century, exasperated by neurologists’ attempts to localize brain functions, French philosopher Henri Bergson protested that memories are not “in” brain cells; it would make more sense to say that brain cells are “in” memories (Bergson). When it comes to memory, the concept of “in” doesn’t apply. Brains, brain regions, and cells do not contain memories. 21st-century neuroscience understands memories differently, as partial reactivations of activity patterns across multiple brain areas (Kandel 1441-60). If a brain can no longer reactivate some patterns, they may seem lost, but not because their material traces have been stolen.

It is easy to criticize a metaphor but harder to find one that works better. The idea of memories as goods stolen by dementia conforms with many people’s emotions as well as their cultural views. The common description of Alzheimer’s disease as a thief conveys the sense of outrage and violation felt by many dementia sufferers and their families. But besides being scientifically inaccurate, the theft metaphor may not help people with dementia or their caregivers as much as Havi Carel’s and Avril Tynan’s transformation idea. If people with dementia are viewed not as robbery or loss victims but as people whose relationships to others have been transformed, dementia might be easier to accept.

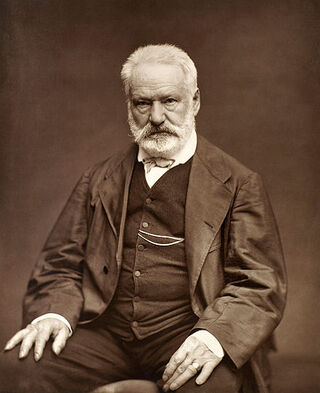

The same holds for the human bodies that make memories possible and that change so greatly over time. In Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, a servant asks the bishop why he isn’t prosecuting Jean Valjean, whom he has been sheltering, for stealing “our” silver. “Is that silver ours?” the bishop asks (Hugo I: 157). He tells her that the silver belongs to the poor. He has kept it for a time, and if a poor man has taken it, that is not egregious. In the spirit of the bishop, I suggest thinking of bodies not as property but as ever-changing gifts with which people identify temporarily. Body identification would make a better metaphor than body ownership. Human bodies depend on other organisms to survive and connect people with all of life. The experiences these bodies have, encoded as memories, don’t constitute property either. We do best when we share our memories with others before our bodies can no longer enact them.

References

Bergson, H. (1896). Matière et mémoire. Paris: Félix Alcan.

Bragance, A. (2004). La Reine nue. Arles: Actes Sud.

Carel, H. (2016). Phenomenology of Illness. Oxford University Press.

Ehrsson, H. H. (2020). “Multisensory Processes in Body Ownership.” Multisensory Perception: From Laboratory to Clinic, pp. 179-94. Edited by K. Sathian and V. S. Ramachandran. London: Elsevier.

Hugo, V. Les Misérables. (1998). [1862]. 2 vols. Librairie Générale Française.

Kandel, E. R., J. H. Schwartz, T. M. Jessell, S. A. Siegelbaum, and A. J. Hudspeth. (2013). Principles of Neural Science. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

“Proper.” (2022). Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed 17 July 2022.

“Propre.” (2022). Larousse Online. Accessed 17 July 2022.

Ramachandran, V. S., and S. Blakeslee. (1998). Phantoms in the Brain: Human Nature and the Architecture of the Mind. London: Fourth Estate.

Tynan, A. (2022). “Counternarrating Loss in Women’s Dementia Fiction in French.” International Society for the Study of Narrative Conference. 28-30 June, 2022.

Weber, M. (2017). [1905]. Die Protestantisiche Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus. Ditzingen: Reklam.