Psychiatry

Is Psychiatry Waking Up to the Truth About Mental Illness?

A leading expert suggests the field drop its focus on brain diseases.

Posted April 13, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Psychiatry has tended to focus on brain disease explanations for mental disorders.

- No diseases to explain mental illnesses have been found in this century.

- Viewing the brain as an information-processing organ may be more productive.

What an exciting turn: In a recent Viewpoint published in JAMA Psychiatry, thought leader Kenneth S. Kendler, M.D., of Virginia Commonwealth University, urged the field to jettison the prevalent idea that some type of brain disease causes each mental illness.1 Instead, he urged that we identify critical causal pathways in the brain that are associated with psychiatric disorders.

It’s likely that mental disorders derive from multiple interacting biological, psychological, and social (environmental) influences. This new conceptualization thus opens the door to the pluralistic causal framework the biopsychosocial model articulates.2,3

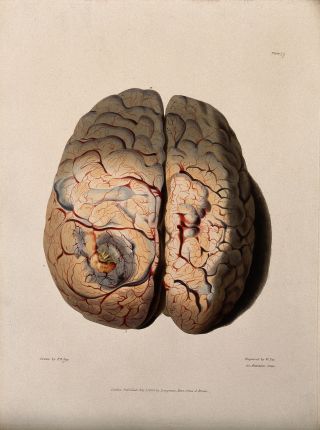

Kendler reports that 19th-century advances in diagnostic pathology did in fact find an underlying, explanatory disease for many patients thought to have a mental disorder. In these patients, plagued by prominent mental and behavioral symptoms, pathologists identified underlying brain diseases causing the symptoms—for example, neurosyphilis, tumors, strokes, and degenerative changes; all are now cared for outside psychiatry in neurology and other medical disciplines. But given psychiatry’s failure to identify new brain diseases causing mental illnesses in this century, it seems we must begin to look elsewhere to explain mental disorders.

Consistent with this idea, Randy Nesse, a founder of the discipline of evolutionary psychiatry, further discouraged modern psychiatry’s obsession with finding brain diseases. Nesse avers that the brain, unlike other organs, is an information-processing organ, and we may no longer find disease explanations for psychiatric disorders in it.4 This idea corresponds to Kendler’s causal pathways mediating mental disorders.

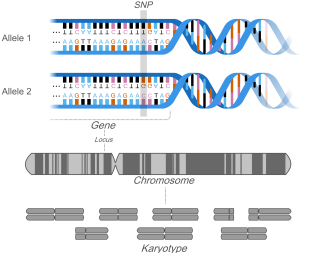

Kendler reports that a more productive area of psychiatric research has identified many risk factors—not diseases or causes—for mental illnesses in these categories: genetic, social/environmental, and psychological. The most potent of these are the well-known genetic predispositions for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression.

In schizophrenia patients, for example, a recent study evaluated the expression of schizophrenia-risk genes in 37 human tissues throughout the body. Only in the brain did they find increased expression of the genes.

While not representing a brain disease, this indicates that the brain mediates the genetic impact of schizophrenia. While other influences (social, environmental, emotional) likely interact with the genes to produce schizophrenia, Kendler proposes that this more modest conceptualization far better matches empirical data and is consistent with a pluralistic approach.

Emphasizing the complexity of genetic influences, he then tells us that increased expression of genetic risk variants for another mental illness—alcohol use disorder—were not found in the brain but rather in liver and gastrointestinal tissues, suggesting that these organs mediate the illness. And studies showed that many key risk genes for obesity are expressed in the brain, another mediating role for the brain in another incompletely understood health problem.

The new direction proposed by Kendler acknowledges the complexity of understanding psychiatric illnesses but provides a more productive, empirically-based direction for understanding mental disorders. It also leads psychiatry in a direction more consistent with a systems approach in which biological, psychological, and social factors are all involved, each facet of this triad a necessary but not individually sufficient explanation for a mental illness.

References

1. Kendler KS. Are Psychiatric Disorders Brain Diseases?-A New Look at an Old Question. JAMA Psychiatry 2024. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0036.

2. Smith RC. Making the biopsychosocial model more scientific-its general and specific models. Soc Sci Med 2021;272:113568. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33423810).

3. Smith R, Fortin AH, VI, Dwamena F, Frankel R. An Evidence-based Patient-Centered Method Makes the Biopsychosocial Model Scientific. Patient Educ Couns 2013;90:265-270. (http://authors.elsevier.com/sd/article/S0738399113000025; last accessed 9/2/23)).

4. Nesse R. Good Reasons for Bad Feelings--Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry: Dutton, 2019.