Health

The Dangers of Medicine’s Pernicious Culture

A rigid medical culture prevents addressing society’s present needs.

Posted September 18, 2022 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- An unconscious culture guides medicine.

- This culture perpetuates medicine’s successful treatment of diseases.

- The culture, however, precludes needed efforts to prevent and treat chronic diseases.

- Only a change in medical education can correct this adverse culture.

Robert Pearl, physician-writer and former CEO of the Permanente Medical Group, recently published an important book, Uncaring: How the Culture of Medicine Kills Doctors and Patients.1 Its message: A deeply entrenched culture prevents necessary changes in medicine’s two key problem areas—prevention and improved treatment of chronic diseases.

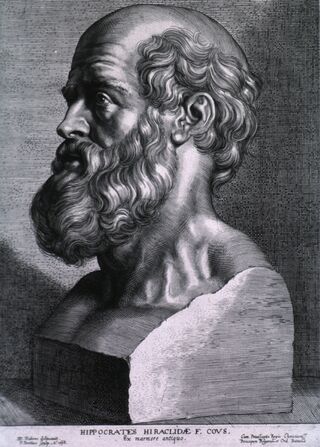

Wisely, Dr. Pearl begins by noting that medicine is not all bad. He recalls its long history of compassion, commitment, and a desire to help people in need, one passed down since Hippocrates in the 5th century BC. Furthermore, he marvels at the wonders of medicine, from organ transplantation to controlling the coronavirus to dramatically increasing our life span.

He then comes to the book’s seminal point: Experts’ and planners’ efforts to improve medicine fail because fixing the various parts of the system will not suffice until we change medicine’s pernicious culture. Dr. Pearl posits that largely unconscious thoughts and attitudes undergird this culture, by which he means that medicine does not itself recognize the emotions and beliefs that drive its adverse behaviors. Dr. Pearl portrays this as a “dark underbelly” that interdicts change in obvious but now ignored directions.

For example, he laments that medicine evinces little interest in preventing diseases. Others have estimated that 80 percent of heart diseases, 80 percent of diabetes, and 40 percent of cancers could be prevented,2 yet medicine prefers to wait until the disease develops to treat it. Although it would save several trillion dollars and prevent many deaths and even more disability and heartbreak, Dr. Pearl avers that, if it switched to a prevention mode, medicine stands to lose not only its now exorbitant remuneration but also its prestige and power.

In another example of medicine’s resistance to change, he argues that, even though COVID-19 created the greatest devastation among those with chronic diseases, medicine makes no effort to improve its care (see my earlier post for an extensive review of the chronic disease problem and the key role of patients’ now ignored mental health and other psychological and social dimensions). Medicine remains oblivious of the human dimensions, which will come as no surprise to readers who have experienced a hurried doctor who pays more attention to a computer than to them.

Dr. Pearl then makes, to me, the most important point of the book because it suggests a definitive solution: Medicine embedded its culture irrevocably through the education of physicians. Boys in White by Howard Becker and colleagues describes students’ transition during medical school from idealistic attitudes of devoting themselves to patients at matriculation, only to, by the end of the first year, place greater value on passing tests. Students’ altruistic motivations further decline over the ensuing three years of medical school and three or more years of residency.3 I do not exaggerate to suggest medical training brainwashes them.

Here’s an example.4 Among those who enter medical school, 49 percent of students express significant interest in psychiatry. However, upon graduation four years later, only 4 percent choose to specialize in this field. Something happens in medical school to turn students against psychiatry. Medicine’s culture establishes an anti-psychiatry mindset that regards mental health and other psychological and social issues negatively.1,5

In spite of his insightful critique of modern medicine, it surprised me that Dr. Pearl advised that medicine will need to take the lead in correcting its culture. This seems a big stretch given medicine’s resistance so far, especially because, as he notes, it doesn’t recognize its adverse culture.

Importantly, however, Dr. Pearl advises that the government and others can play a role in effecting a new direction. He concludes by cogently outlining the change process medicine must undergo, whether of its own volition or at the behest of others: i) admit the problem and the need for change; ii) commit to action; iii) embrace others and learn from their successes; iv) collaborate with others; v) resurrect the old values of caring for the patient.

All told, anyone interested in understanding how to improve medical care will find Uncaring a critical contribution. Dr. Pearl hit the nail on the head when he pinpointed medicine’s perverse culture as the point of departure in correcting society’s greatest present health problems: prevention of diseases and better management of chronic diseases.

Uncaring will, in my opinion, establish itself alongside such classics on medicine’s adverse culture as Boys in White3 and Paul Starr’s The Social Transformation of American Medicine.5

References

1. Pearl R. UnCaring--How the Culture of Medicine Kills Doctors & Patients. New York: Public Affairs; 2021.

2. The Growing Crisis of Chronic Disease in the United States. 2019. (Accessed May 31, 2019, at https://www.fightchronicdisease.org/sites/default/files/docs/GrowingCri….)

3. Becker H, Geer B, Hughes H, Strauss A. Boys in White--Student Culture in Medical School: Routledge; 1976.

4. Goldacre MJ, Fazel S, Smith F, Lambert T. Choice and rejection of psychiatry as a career: surveys of UK medical graduates from 1974 to 2009. Br J Psychiatry 2012.

5. Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers; 1982.