Environment

Inner Change to Tackle the Climate and Biodiversity Crisis

The crucial role of mindset change for achieving sustainability.

Posted April 11, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Addressing environmental crises has long been seen as a technological or economic challenge.

- Now we are seeing an inflection point where the crucial role of mindset change for achieving sustainability is being recognised.

- Respected global science-policy initiatives now talk about the need for 'inner change' to achieve sustainability.

Pick up any mainstream book about solving the climate and biodiversity crisis, such as Bill Gates’ book about climate change, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, or Dieter Helm’s book, Natural Capital, and you'd be forgiven for thinking that technology and economics are the only solutions available.

But another view is gaining ground, centred on the importance of ‘inner change’ to the mindsets and worldviews of everyday people. This doesn't discount the importance of ‘top-down’ solutions, such as environmental regulation, economic policy and technological innovation, but recognises that these levers alone are insufficient to solve the deep environmental crisis society now faces.

Individual mindsets and worldviews matter because they affect what we choose to buy, how we travel, work and spend our leisure time. All of these, cumulatively, across many people, have a huge impact on the environment. Our attitudes and behaviours also influence—and are influenced by—other people, and so achieving environmental sustainability will likely involve tipping points of rapid social change. Many organisations, including policy agencies and environmental charities, are beginning to see the importance of mindsets and worldviews for creating such tipping points to successfully achieve environmental sustainability.

In a sense, none of this is new. Philosophers like the Norwegian Arne Naess discussed the importance of self-identity and worldviews as a key aspect of sustainability back in the 1970s, and there have been academic books and journal papers on these topics. Whole journals now specialise in topics such as Environmental Psychology and the interdisciplinary field of systems thinking incorporates these ideas. Yet, these discourses have always tended to be at the margins of a mainstream ‘techno-scientific’ approach, where technological innovation is seen as our saviour for the destruction of the environment. Yet, there is increasing recognition that the tools we are trying to use to solve these issues may actually be part of the problem. Many new technologies have adverse consequences on nature, and our fixation on economic growth has accelerated environmental decline. It's tempting to simply double down and work harder on the same approaches. After all, ‘if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail’, as the American psychologist Abraham Maslow once stated.

In the face of challenging problems like climate change and global biodiversity loss (often called ‘wicked’ problems on the basis that both their causes and solutions are intimately tied up with conflicting perspectives), we need new tools. Technological innovation and economic regulation don't really get at the root causes of the environmental crisis. Instead we need to change mindsets and worldviews which, multiplied over many people, leads to deep cultural change.

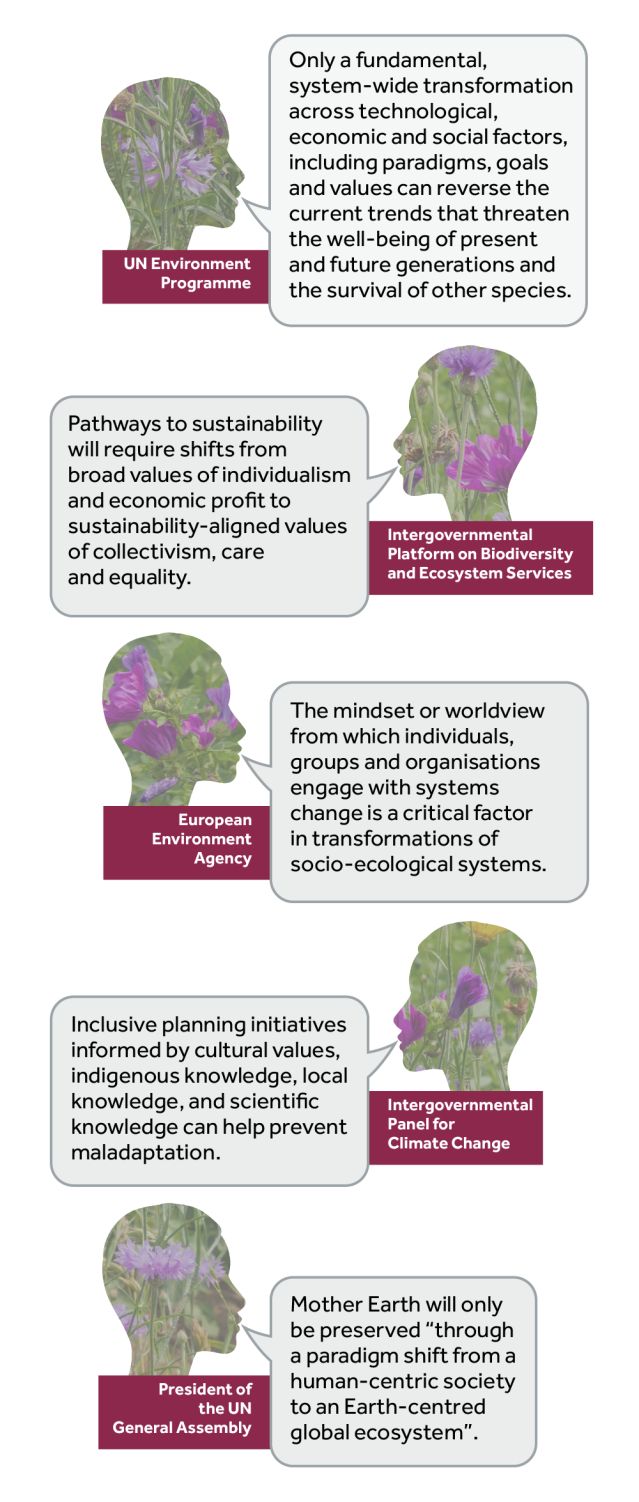

Rather than these ideas being niche, they are now entering mainstream environmental science-policy discourse. Respected global initiatives from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to the United Nations Environment Programme talk about the need for inner change to achieve sustainability. The European Environment Agency has produced a particularly progressive think-piece on the role of self-identity as a key driver and solution to the climate and biodiversity crisis.

The next question is how to operationalize changes to our culture. How can they be wisely stewarded? We should be cautious navigating the tricky pathway between imposing cultural change, versus a laissez faire attitude of anything goes individualism; we need to recognise and celebrate a plurality of viewpoints, while suppressing anti-social and ecocidal worldviews.

Acknowledging and celebrating a diversity of views is something that features in the founding visions of many countries. E pluribus unum meaning ‘From the many, one’ was the founding motto of the United States and inscribed into its coins, whilst in varietate concordia (‘united in diversity’) is the motto of the European Union. Yet, the great social progress that has been made in many countries in the modern era has arguably stalled. Studies suggest materialistic and individualistic values have become dominant in the majority of countries over the last 50 years, and these can hamper progress on environmental problems.

There are important lessons we can learn from ancient and indigenous cultures, though we must ultimately develop a new vision for the modern world. Any group identity might need to extend beyond nation-states to gain a sense of global citizenship, maybe even including solidarity with other species beyond humans.

A renewed focus on ‘inner’ human development is perhaps warranted, and initiatives like the Inner Development Goals, which seek to provide a framework for inner transformation towards more sustainable mindsets, are very timely. Other global initiatives such as the United Nations Development Programme seek to operationalise these mindset changes too, such as through their Conscious Food Systems Alliance aiming to transform food producer, regulator and consumer practices towards sustainability by focusing on a psychological reconnection with nature. Wildlife charities such as the RSPB and UK Wildlife Trusts similarly aim to re-connect young people to nature, whilst organisations such as the Mindfulness Initiative focus on inner change in policymakers to help deal more effectively with the climate crisis.

In an era where we seem to be bombarded with bad news about the state of the environment on a daily basis, perhaps there is some cause for hope and optimism. Of course, we have a long way to go to enable inner change towards a genuinely sustainable human civilisation, but we can take solace in the fact that we each have an important role to play, and the social fabric linking us all means that change, when it comes, can happen very quickly.