Identity

How Do Nature and Self-Identity Interact?

Biodiversity loss and self-identity are linked in a dynamic relationship.

Updated February 22, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Reversing biodiversity loss needs focus beyond economic and technological fixes to deal with deeper culture

- Scientific syntheses show how self-identity and the environment are linked in ‘vicious cycles’ of decline

- If we don’t understand these feedback processes, our solutions to biodiversity changes will be ineffective

The previous administrator for the UN Development Programme, Gus Speth, talked about how when starting his career he used to think that the world’s environmental problems could be solved by good science, but after decades working in the field he concluded the root causes lie in our mindsets and culture.

“I used to think that top global environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. I thought that with 30 years of good science we could address these problems, but I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed, and apathy, and to deal with these we need a spiritual and cultural transformation. And we scientists don’t know how to do that.” —Gus Speth.

I was involved in a review paper, published this winter 2022 in the journal The Lancet Planetary Health, which confirms how our self-identity is a crucial factor in the fight to restore the world’s deteriorating environment. As part of a group of interdisciplinary researchers we showed how a highly individualistic identity—seeing ourselves as separate from others and the natural world—is a root cause of many environmental problems.

Working across disciplines

The review involved environmental scientists, psychologists, sociologists and policymakers and drew together evidence from a wide range of fields to test several hypotheses, related to how our self-identity can lock us into ‘vicious cycles’ of environmental decline.

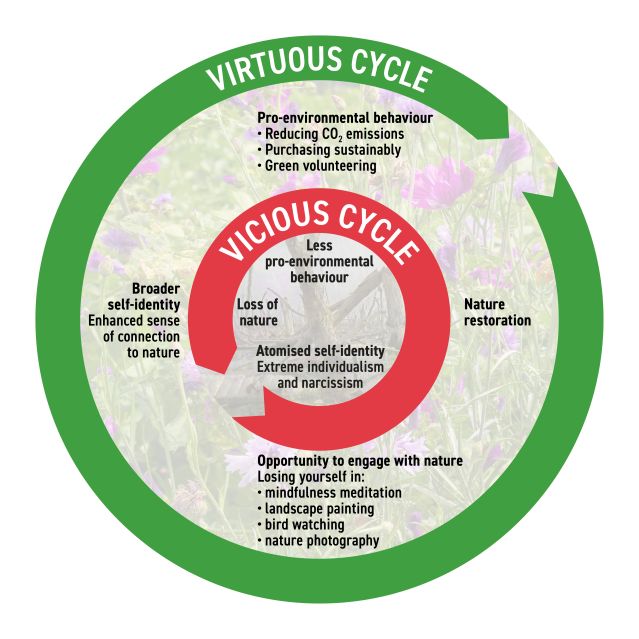

‘Vicious cycles’ are feedback processes where a self-reinforcing feedback loop makes a negative state persist or worsen. They are known in social systems (such as ‘poverty traps’, as well as cycles of alcoholism and depression) and in ecological systems too, such as how climate change both causes—and is itself exacerbated—by ice sheet melting and forest die back. In this study, we explored how previously hidden vicious cycles link social and ecological systems together. In particular, we found that self-identity is implicated in a vicious cycle of environmental decline, and this may explain why previously attempted solutions to the biodiversity and climate crises have been ineffective.

Self-identity is the integrated image someone has of themselves, and is determined by a complex interplay of social context and individual history. There is large variation between people, with some having a highly individualistic self-identity—a very strong sense of ego, seeing themselves as discrete from others and the natural world, while others feel a greater sense of overlap and connection (that previous researchers have respectively termed greater ‘social connectedness’ and ‘nature connectedness’, and which can be assessed by various questionnaire surveys).

Biodiversity and our sense of connection to nature

One of the hypotheses we tested was that people with lower nature connectedness carried out fewer behaviours to improve the environment. They are less likely to recycle, actively reduce their carbon footprint or volunteer for environmental organisations. These actions result in nature being less protected, meaning plants and wildlife disappear from around our towns and cities. As a consequence, people have even less opportunity to engage with nature, which has an effect on their self-identity—living in highly urbanised environments tends to reduce the sense of nature connection, while spending time experiencing nature enhances it. So, self-identity and environmental quality change in tandem, in this case in a worrying spiral of decline.

Vicious cycles in institutions

It appears these vicious cycles are at play in many countries, reflecting growing trends of disconnection to nature, as well as growing individualism and nationalism, in the majority of countries over recent decades. These changes in self-identity are also thought to ‘cascade upwards’ to affect institutions such as government and the economy. Pointing to ex-President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ policy, we suggested that changes to self-identity in national leaders might explain the damaging removal of environmental protection and reduced international cooperation, which is essential to solve globalised problems such as climate change, biodiversity loss, ocean acidification and air pollution.

In corporations, highly individualistic attitudes can lead to a strong focus on generating profits at the expense of care and responsibility towards nature. There is a danger the consequent environmental decline aggravates poverty, inequality and mass human displacement, lead to a further highly-individualistic ‘dog-eat-dog’ mentality, where people only look out for themselves or their close family.

Turning things around

Yet, there is hope, because we found there are mechanisms by which these trends can be reversed. Expanding our sense of self-identity to include others and the natural world creates an attitude of care and responsibility. The actions that follow lead to nature improvement, for example restoring plants and wildlife in our urban areas. This in turn allows greater opportunity to engage with nature, further enhancing a sense of nature connectedness. Instead of a vicious cycle, we can turn things around to create a virtuous circle of human-nature restoration.

References

Oliver, T.H., Doherty, B., Dornelles, A., Gilbert, N., Greenwell, M.P., Harrison, L.J. et al. (2022). A safe and just operating space for human identity: a systems perspective. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6, e919-e927. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00217-0