Intelligence

This Disabled Parrot Invented a Way to Preen Himself

Bruce the kea demonstrates deliberate and flexible tool use.

Posted September 14, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Bruce, a disabled kea parrot lacking his upper bill, uses pebbles grasped between his tongue and lower bill to preen himself.

- His unique preening behavior appears to be a deliberate innovation for self-care, as a direct consequence of his disability.

- Bruce’s behavior adds to the evidence that kea are highly intelligent and flexible problem-solvers.

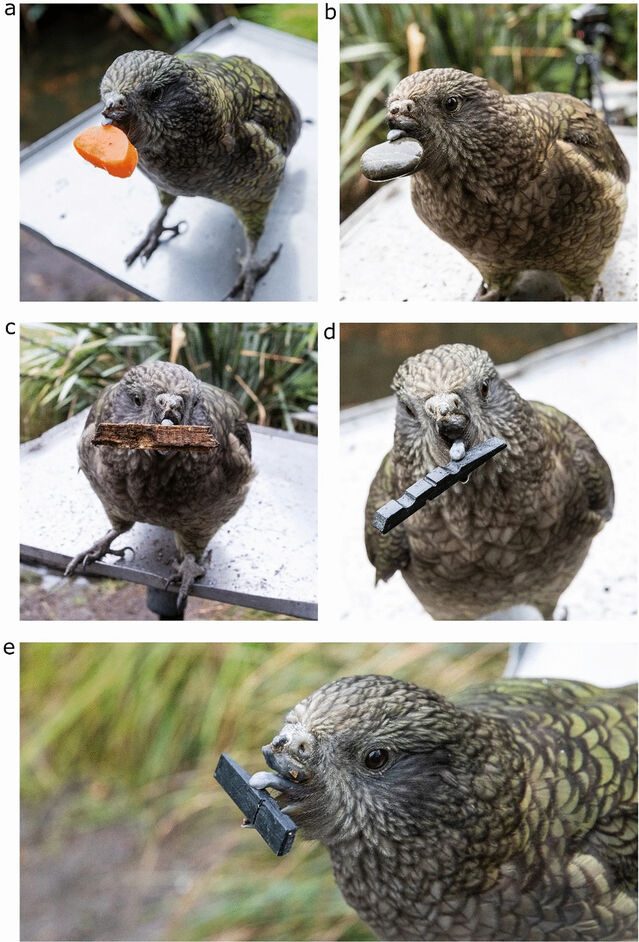

Pictured above is Bruce. Bruce is a kea (Nestor notabilis), a species of alpine parrot native to New Zealand. He’s eight years old and lives at the Willowbank Wildlife Reserve in Christchurch. What sets him apart from the other kea in that aviary is his disability: Bruce lost his upper bill in an accident when he was young.

Remarkably, this does not stop him from looking his best. Bruce appears to use small pebbles to preen himself. He selects a pebble, wedges it between his lower jaw and tongue, and moves it along his feathers. The action seems similar to how other kea preen themselves by clasping and grinding their feathers between their upper and lower bills.

Bruce’s special grooming behavior caught the attention of keepers at the Willowbank Wildlife Reserve. They alerted the Kea Team of the Animal Minds Lab at the University of Auckland. In a recent paper, the researchers described and quantified observations of Bruce and other non-disabled kea. They concluded that Bruce’s flexible, deliberate, and context-appropriate behavior represents an ingenious solution to his lack of bill, as well as reflecting his species’ knack for innovation and problem-solving.

Parrot Problem-Solving

Although known for their intelligence and curiosity, kea do not habitually use tools in the wild. But to Kata Horváth, a Ph.D. candidate at the ELTE Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary, and one of the study’s authors, Bruce’s pebble-preening looked like an example of tooling.

“Tooling requires an interaction between the tool and a surface so that by manipulating the tool, a change or movement in the surface is caused in an anticipated way,” Horváth says. “Thus, for example, throwing a piece of food covered by a hard shell to open it is not tooling; using a stick to scratch an itch would be tooling.”

Tooling, though considered a complex behavior, is not necessarily flexible. Tool use can be an innate, rigid behavior or an innovative, flexible response to a new problem.

To investigate whether Bruce’s unique preening behavior was truly innovative, Horváth and her colleagues recorded observations of Bruce preening and manipulating other objects over nine days and compared his behavior to that of the non-disabled kea with whom he shares an aviary.

Overall, the researchers identified five lines of evidence supporting the idea that Bruce’s tooling behavior is deliberate:

- In over 90 percent of instances in which Bruce picked up a pebble, he then preened with it, suggesting he picked up the pebble with the intent of using it as a preening tool.

- In 95 percent of instances in which Bruce dropped a pebble, he retrieved or replaced it and continued preening.

- Bruce selected pebbles of a particular size and shape for use as tools, rather than randomly sampling available pebbles in his environment.

- While Bruce manipulated non-pebble objects at a similar rate to other individuals, he was the only kea ever observed using pebbles for preening.

-

When other kea did interact with stones and pebbles, they chose larger stones than those selected by Bruce.

“Based on these five lines of evidence, Bruce’s pebble preening behavior is clearly an intentional innovation — and he did this all by himself!” says Horváth. “He wasn’t trained, nor could he observe other kea engaging in similar behavior. He innovated this behavior to overcome a struggle he faced because of his injury.”

A Very Capable Kea

Bruce’s deliberate tooling behavior provides further evidence for the highly flexible problem-solving abilities of kea, suggesting that when there is an ecological need, kea can excel at innovating tools. Horváth and her colleagues say that high-level intelligence, together with curiosity, could be a driver for technical innovations not only in the kea, but possibly in other species, as well.

Finally, Horváth wants everyone to know that Bruce has adapted to his disability in his own way and is doing wonderfully.

“Visitors to the wildlife reserve often ask why he has no prosthetics,” she says. “The answer is he doesn’t need them at all. A prosthetic beak would probably cause him much more stress due to the frequent vet visits and the need to re-adapt his behavior.

“He is an extraordinary kea who has perfectly overcome his disability!”

References

Bastos, A.P.M., Horváth, K., Webb, J.L., Wood, P.M., and Taylor, A. H. Self-care tooling innovation in a disabled kea (Nestor notabilis). Sci Rep 11, 18035 (2021). Doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97086-w.