Suicide

What Is the Suicidal Mode?

Suicidal self-harm usually happens in an altered mental state.

Posted January 7, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Mental pain can lead to high emotional stress.

- High emotional stress is often related to dissociative mental states.

- The concept of the suicidal mode aptly describes the experience of a dissociative on/off condition.

- Understanding the suicidal mode is key for safety planning because it helps identify personal warning signs.

“This was not me acting like this. I was not myself. I felt as if I was on auto-pilot." Experiences like this have been reported by many people experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors—but surprisingly, this aspect of suicidal behavior is rarely mentioned in the professional literature.

Here I want to discuss two important concepts that health professionals and their patients must know in order to understand the mental experience of the acutely suicidal person: dissociation and the suicidal mode.

Suicidal Dissociation

In the narrative interviews we conducted with patients with a history of attempted suicide, we found that most of them were at a loss when trying to explain their mental state in the acute suicidal crisis. For example, here are some things a 30-year-old man told me after a suicide attempt:

“I got into a kind of trance. I don't know how else one could call this state. Suddenly, one does not perceive anything what happens around.”

“When I cut myself it did not hurt.”

“I swallowed the pills without thinking much. I emptied the bottles and stuffed the pills in me.”

“I did not realize it. I knew what I was doing. But I did not feel it. It did not hurt.”

It is well known that high levels of emotional stress can lead to emotional numbing, to feeling detached from the body, and to indifference to physical pain. Typical symptoms of dissociative disorder include changes in the perception of one’s self, one’s senses, the environment, and time. These symptoms are transient and may vary greatly in severity.

Dissociative symptoms typically occur in connection with acute trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress reactions, and, sometimes, panic attacks. Typical descriptions of behaviors related to dissociation include functioning in “autopilot mode,” not feeling connected to one’s own body, or having no sense of somatic pain (analgesia). Some suicidal dissociative states can last for hours or even days.

The concept of dissociation includes the notion that the sense of self is made up of subsystems that can become disconnected under high levels of stress. In the clinical suicide literature, this crucial aspect of life-threatening suicidal crises is generally neglected.

The Suicidal Mode

Suicidal dissociation is directly related to the concept of the suicidal mode. The suicidal mode was introduced in cognitive-behavioral therapy by Aaron Beck and David Rudd (1).

A mode is defined as a response pattern to exceptional demands, incorporating cognitive, emotional, physiological, and behavioral systems of personality organization. Once established—that is, after the first suicidal action—a mode will be switched on by a typical triggering event.

In suicide research, the term suicidal mode has proven particularly useful in understanding the sudden onset of acute suicidal mental states. For individuals with a history of attempted suicide, the threshold for activation of the suicidal mode will be lowered.

Cognition in the suicidal mode is dominated by pervasive hopelessness, with the individual seeing no other solution than to put an end to an unbearable mental state. The focus on long-term life goals is lost, as if the person was struck by a sudden “mental myopia.”

Emotionally, the suicidal mode is usually accompanied by anxiety, panic, embarrassment, humiliation, and self-hate. Bodily functions reflect an acute stress reaction with high inner arousal. The behavioral system is activated and experienced as an impulse for flight.

A suicidal mode typically is an on/off mechanism and can occur suddenly. Triggers can be either internal (e.g., by a thought, feeling, or image) or external (situations, places, people). Typically, patients describe the sudden switch back to normal, immediately following a suicide action, such as cutting, overdosing, or jumping from high places.

A prominent example is Kevin Hines, who survived a suicide attempt by jumping from the Golden Gate Bridge in the year 2000 (2): “I hit free fall, and that second, I knew what I did was a terrible mistake.”

The Neurobiology of the Suicidal Mode

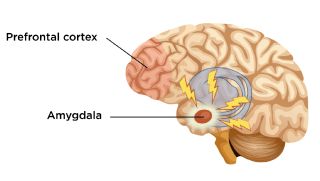

The ability to reflect on a current emotionally stressful situation in the context of one’s own autobiographical memory is largely dependent upon the full operations of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and its connections. The PFC as the highest cerebral organ in guiding complex behavior has connections to the emotional brain, the limbic system, and the amygdala.

During uncontrollable stress, the activation in the amygdala, the emotional brain’s alarm center, is turned up, while at the same time, the function of the PFC is turned down. This means that the problem-solving capacities of the PFC are severely impaired. Yet the ability to put an acute emotional crisis into perspective and maintain long-term identity goals is crucial for coping with high levels of stress and mental pain.

In a small functional MRI study (3) we selected sequences from the patients’ suicide narratives in which they talked about emotional stress and pain and the suicide actions, such as taking pills, cutting, etc. After we had to exclude some study participants because of technical problems, we ended up with eight complete fMRI scans we analyzed.

The results showed that when patients talked about mental pain and emotional stress, there was a significantly reduced neural activation in a specific region of the PFC, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), and the medial prefrontal cortex. These regions of the PFC are related to working memory, self-reflection, appraisal of internally generated emotions, past and future events, and possible rewards—experiences we relate to our sense of agency.

Our interpretation of the results was that with the script-driven recall, we had switched on the suicidal mode, which for our patients meant the deactivation of a PFC brain region associated with the ability to decide rationally how to deal with emotional stress and mental pain. We then looked at the brain activation of the suicide action scripts (buying drugs at the pharmacy, getting the pills out of the blisters, etc.), and we found a relative increase of neural activation in an area of the PFC, the so-called premotor cortex associated with the initiation of movements and controlling behavior.

The findings from this study can be seen as supporting the theory that starting the suicide action may be a proactive way of escaping from the helplessness and from the experience of being trapped with unbearable pain. If we take this idea further, we can assume that a suicidal action, such as overdosing, could be recorded in the autobiographical memory as “useful” behavior, because it brings immediate relief and terminates the unbearable state of mental pain.

This could explain why after a suicide attempt, the risk of future suicidal behavior is highly increased and remains so over decades, because the engram (the memory trace) of the suicidal action itself may be saved in the brain as positive rather than a negative experience, as one might expect.

Conclusion

The concepts of dissociation and the suicidal mode are key psychoeducational elements in helping people to understand their own suicidal behavior. The concepts make sense to patients because they reflect their own experiences. Furthermore, the two concepts are important for safety planning by developing the personal warning signs that can be applied before the suicidal mode takes over.

In my next article, I will explore the question of how we can reach people at risk of suicide who don’t seek help.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For immediate help in the U.S., 24/7, Call 988 or go to 988lifeline.org. Outside of the U.S., visit the International Resources page for suicide hotlines in your country. To find a therapist near you, see the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Rudd, M.D. "The Suicidal Mode: A Cognitive‐Behavioral Model of Suicidality." Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 30, no. 1 (2000): 18-33.

Reisch, T., E. Seifritz, F. Esposito, R. Wiest, L. Valach, and K. Michel. "An fMRI Study on Mental Pain and Suicidal Behavior." Journal of Affective Disorders 126, no. 1 (2010): 321-25.

Hines, K. “Kevin Hines, Survivor, Storyteller, Film Maker”. Accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.kevinhinesstory.com/.