Productivity

Can Maintaining a Strict Routine Be an Act of Freedom?

Setting rules for ourselves is the easy part—sticking to them is much harder.

Updated March 18, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- It can be the ultimate expression of individual autonomy to make commitments to yourself.

- Paradoxically, limiting your choices now can expand your options later.

- We all need to find a routine that works for us and not follow others' advice unreflectively.

Like many people who aspire to be writers, I share the pastime of reading about the routines of successful writers—a popular pastime, as shown by many online articles and books on the topic (such as in the references below).

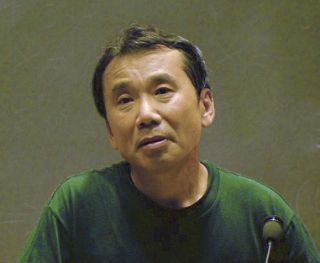

In his recent book about writing, Novelist as a Vocation, acclaimed author Haruki Murakami describes his routine, which belongs to the popular school of “write every day” but adds the more novel element of “write the same amount every day”:

When writing a novel, my rule is to produce roughly ten Japanese manuscript pages (the equivalent of sixteen hundred English words) every day. … On days where I want to write more, I still stop after ten pages; when I don’t feel like writing, I force myself to somehow fulfill my quota.

He goes on to explain that if he wrote too much one day, he might not write anything the next, so he prefers to maintain steady output: “I punch in, write my ten pages, and then punch out, as if I’m working on a time card.” (He doesn’t write for a fixed amount of time, though, as is also common.)

This he regards as controversial, being contrary to many people’s—and many artists’—impressions of how an artist should work. “But why must a novelist be an artist?” he asks on the next page. “Who made the rule? No one, right? So why not write in whatever way is most natural to you?” Aside from the question of whether novelists are artists—note the title of his book refers to “vocation”—his general point applies to all creative people, including but not limited to writers.

The Paradox of Commitments to Oneself

Murakami supposes that his strict writing routine violates what some regard as the artistic “ideal” of freedom, by which artists are presumed to follow their whims and create wherever and whenever the muse appears to them. But he argues that freedom really means “that we are able to do what we like, when we like, in a way we like without worrying about how the world sees us”—including self-appointed watchdogs of the artist class. After all, if all artists are expected to conform to a single idea of behavior, how free can they be?

This description of freedom also recalls autonomy as written about by the philosopher Immanuel Kant. His idea of autonomy focuses on making choices independent of inclination or desire as well as external pressure, but it also includes the ability to make commitments to others and to oneself. Making a choice now that limits your choices later can be considered the ultimate expression of autonomy and can be very meaningful (such as in romantic relationships, as I wrote before).

Murakami’s self-imposed goal (and limit) of 10 pages per day certainly constrains his autonomy on any given day. It forces him to write 10 pages when he doesn’t feel like it and to stop writing after 10 pages when he feels like writing more. But it is an expression of his autonomy that he sets this rule for himself, and this enables him to write enough pages over the long run to sustain his own writing and publication schedule. In other words, limiting his options each day gives him more options over his career.

Making Commitments to Yourself

But making a commitment to yourself is the easy part—keeping it is difficult. (Just think of how many New Year’s resolutions are made every January 1, only to be abandoned by… well, January 2.) Many of us are unlikely to break promises we make to other people, but we all too easily break ones we make to ourselves. We don’t want to let others down, especially those close to us, but then what explains our willingness to let ourselves down?

Kant was adamant that, as well as having duties to others, including the promises we voluntarily make to them, we also have duties to ourselves, including the duty to keep promises we make ourselves. Furthermore, there is no reason to take these less seriously, because we are all persons capable of autonomy, possessed of dignity, and deserving of respect. Just as we have moral obligations to others, we have moral obligations to ourselves—especially when we commit to doing something in our long-term interest.

Nonetheless, we are all too quick to let ourselves down, forgetting our promises to ourselves by rationalizing some way out of them. This only shows that we don’t take ourselves importantly enough, not just as persons worthy of respect but also as persons who have to earn that respect by keeping our promises. (This applies also to self-compassion, which can seem much more difficult than giving compassion to others.)

Summing Up…

Even if we don’t follow Murakami’s precise routine, we can all learn from his commitment to himself, which he maintains regardless of motivation or lack thereof. We can also emulate his autonomy and authenticity in choosing his own way of living, regardless of the opinions of others. Writing 10 pages a day, no matter how difficult, is what works for him, but it may not work for me or you. Many people follow the “write first, edit later” rule, but this does not work for everybody, either. We each need to find the routine that works for us and then stick to it—which, at the end of the day, no matter how well you prepare or establish habits, takes an act of willpower. (No easy tricks for this, sorry!)

References

For example, see "The Daily Routines of Great Writers," The Marginalian, November 20, 2012, and Sarah Stodola, Process: The Writing Lives of Great Authors, 2015.