Philosophy

Why You Should Be Careful How Much Responsibility You Take

Daredevil shows us why feeling the "weight of the world" is not healthy.

Updated December 29, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- A sense of responsibility is essential to lead an ethical life, but it must be applied accurately.

- Although it seems noble, no one can or should hold themselves responsible for things they had no control over.

- Superheroes like Daredevil serve as examples of excessive responsibility and the suffering it can lead to.

In my last post on Matt Murdock, also known as Daredevil, we saw a pattern regarding his feelings of self-worth: He minimizes the positive contributions he makes as a superhero, focusing too much on the negatives such as putting his loved ones at risk and causing incidental harm to others, only to be reminded of his true value the next time he saves a life.1

For instance, after he and the villain he’s fighting at the time almost destroy a family’s home, Daredevil swears to quit, saying, “I once believed I became a swinging superhero to help people. Instead, I’m destroying them. … For the first time in years, I can see things clearly. I wasn’t helping anybody but number one!” Yet soon afterward he’s back in action, acknowledging that “I’ve got special abilities, and because of that, I’ve got responsibilities—not only to myself, but to everyone” (Daredevil #128, December 1975).

So Much Responsibility

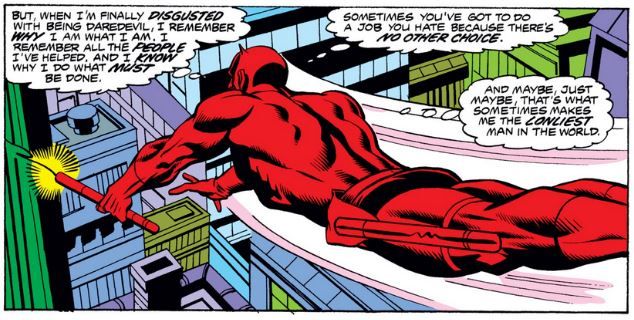

The sheer frequency of these episodes suggests that it is Matt Murdock’s sense of responsibility that pushes him to continue being Daredevil despite his recurring doubts about the value of doing so. As he said in yet another period of uncertainty about his chosen path in life:

when I’m finally disgusted with being Daredevil, I remember why I am what I am. I remember all the people I’ve helped. And I know why I do what must be done. Sometimes you’ve got to do a job you hate because there’s no other choice. (Daredevil #143, March 1977)

Although it is definitely not good that he resents being Daredevil enough to say he “hates” it, this statement emphasizes the importance of responsibility to him, motivating him to continue his heroic life despite the numerous costs to him and his loved ones.

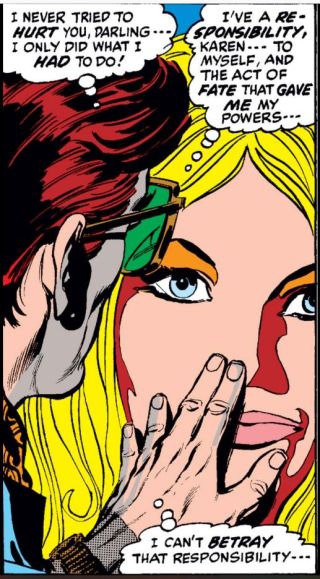

Sometimes Matt suggests that the accident that blinded him while enhancing his other senses—after he pushed an elderly man out of the way of a truck carrying radioactive waste that splashed onto his face—also vested him with the responsibility to use them to help others. Standing in front of a picture of his early love Karen Page on a movie poster and mourning their breakup, Matt thought to himself, “I’ve a responsibility, Karen—to myself, and the act of fate that gave me my powers—I can’t betray that responsibility—not for you, God help me—not for anyone” (Daredevil #78, July 1971).

If this seems like too much weight for one person to bear, keep in mind that, like many other heroes (super or otherwise), Matt has an exaggerated sense of responsibility. (I’m sure it has something to do with “great power,” as another hero’s uncle famously said.) Nonetheless, it is an important source of motivation for Matt to keep going as Daredevil even when he doubts his value.2

Stepping away from Daredevil for a moment, it is responsibility that keeps a lot of us going when we doubt our own value in certain areas of our lives. This is most clear when thinking of our roles in our families, households, or communities: Even when we doubt the good we’re doing, we realize we made meaningful promises or commitments to people we care about, and as a result we feel responsible to those people, which keeps us in the game even when we have momentary lapses in motivations or willpower.

This also applies to our work, even when we might “hate” it. Unlike family and community, though, jobs are often more transactional in nature—although more cynical employers can try to foster a sense of “family” and “responsibility” to make it easier to exploit their employees. But Matt obviously considers his “job” as Daredevil to be more of a “calling,” especially when he attributes his accident to divine intervention, making this particular responsibility as difficult to shed as any he has to his loved ones—even when those responsibilities conflict.

Responsibility to Do the Impossible

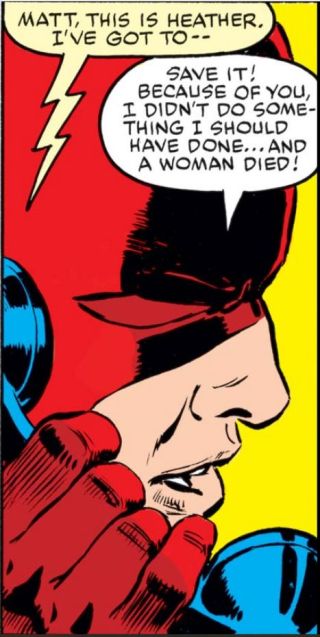

Matt’s oversized sense of responsibility also extends to “tragic dilemmas” when several people need his help and he must choose between them, knowing full well that whoever he chooses not to help may suffer as a result. After Matt broke up with a later girlfriend, Heather Glenn, she called him for help, but when he rushed to her apartment he discovered she was drunk and had faked distress simply to lure him over. Unfortunately, Matt had been in such a hurry to get to her that he passed up a violent domestic dispute along the way, which he later learned turned deadly. (Somewhere, Peter Parker simply nods.) When Heather called on him again, Matt told her, “Because of you, I didn’t do something I should have done… and a woman died!” Heather replied, “I’ll die too,” but her voice cut out when Matt yanked the phone out of the wall in frustration (Daredevil #220, July 1985).

Soon afterward, Heather took her own life, for which Matt also felt responsible, thinking it was “my fault we broke up… my fault she got so messed up… if I’d tried to understand her,” and so on. After his best friend Foggy Nelson read her suicide note to Matt and, as an amateur therapists, asked him how that made him feel, he answered, “Guilty. Guilty as sin.” When Foggy put his lawyer hat back on and tried to argue that he shouldn’t feel guilty, Matt said, “Maybe not. But still, she’s dead… and in some way, I’m responsible. It’s my fault” (Daredevil #220, July 1985). After Heather’s funeral, when Matt’s friend (and Daily Bugle reporter) Ben Urich asked him—with even less sensitivity than Foggy had—if he felt responsible for Heather’s death, Matt went through all the things he could have done and all the things he couldn’t, and concluded, “I don’t know. I’ll never know” (Daredevil #221, August 1985). We can be reasonably sure he does, even if he doesn’t know exactly why.

When he blames himself for tragic events even without having played a direct role in them, Matt shows us how much excess responsibility he takes on, regardless of whether he could have possibly prevented them. He even felt responsible for everything that happened to his college love, Elektra, including becoming an assassin and eventually being killed by the psychopathic Bullseye. Despite having been in her life a relatively short time, Matt asked himself at one point, “What made me hurt you so? Did I fail you in some way—or were you possessed by some awful inner demon that made you kill, and kill…” (Daredevil #182, May 1982).

Conclusion

Like many of us, Matt tries to do good in the world, but even when he does—and he certainly does more than anyone could possibly be expected to do—he still feels responsible for the harm he couldn’t prevent, not to mention the harm that occurred as a byproduct of his heroic endeavors. He needs to recognize that he shouldn’t feel responsible for outcomes he had no control over, especially if there was no way he could have changed them (such as in cases of tragic dilemmas) or if other people are in fact responsible for them. For example, on many occasions, Matt stops short of killing Bullseye, and even saves his life when he can, only later to feel responsible for the people Bullseye kills afterward, even though that was Bullseye's choice, not Matt's.

This attitude may be seen in generally good people, whether superheroes or not, who are hesitant to deny responsibility when there’s any chance it might apply, for fear of not taking responsibility when it is appropriate. For people who are particularly susceptible to this, there’s a lot to learn from the example of Matt Murdock, who suffers a significant negative impact from his excessive feelings of responsibility—which leads to further issues that we’ll discuss in the next post.

NEXT: Matt Murdock's Identity Crisis: To Be or Not To Be Daredevil

References

1. This post and the others in this series are adapted from my new book, A Philosopher Reads... Marvel Comics' Daredevil: From the Beginning to Born Again (Ockham Publishing 2024).

2. For other examples of superheroes assuming more responsibility than they should, see my work in The Virtues of Captain America: Modern-Day Lessons on Character from a World War II Superhero (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2014), pp. 58–63; “The Otherworldly Burden of Being the Sorcerer Supreme” in Mark D. White (ed.), Doctor Strange and Philosophy: The Other Book of Forbidden Knowledge (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2018), pp. 177–190; and “Panther Virtue: The Many Roles of T’Challa,” in Edwardo Pérez an Timothy E. Brown (eds), Black Panther and Philosophy: What Can Wakanda Offer the World? (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2022), pp. 53–60.