Depression

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) Treats Depression

A new, noninvasive treatment for depression.

Posted January 28, 2014 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Depression affects 121 million people worldwide and 35 million Americans. It is estimated that 60 percent of the depressed population does not receive adequate care.

Among those that do receive care, treatment resistant depression represents a severe category which does not respond to traditional methods, be it therapy, multiple types of medications or a combination of the two. Recent studies indicate that TMS, or Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, may provide relief without a pill.

This is about to get complicated, but I’ll simplify it as much as possible. The brain is comprised of 85 billion brain cells better known as neurons. These communicate in two ways. Within the neuron, electrical energy carries a signal from one end of the cell to the other. In between the neurons, in the synaptic cleft, brain chemicals (called neurotransmitters) are released to carry a message from one cell to another.

Antidepressants work on the chemical side of the brain affecting various neurotransmitters including norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine and others. The predominant theory in biologic depression is that these brain chemicals become out of alignment and that meds “normalize” brain chemistry. These meds can work in a variety of ways by increasing or decreasing neurotransmitters, acting as substitute neurotransmitters, regulating the receptors that these chemicals bind to… The list goes on and is extremely complex.

TMS, on the other hand, targets the electrical activity within the neuron. On the surface this sound completely different than antidepressants, but it’s not. The electrical activity inside each neuron stimulates chemical release into the gap between the neurons. Though the exact mechanism of action is not known, it is thought that magnetic impulses from TMS stimulates nerve cells which increases brain activity. This triggers a release of brain chemicals into the synaptic cleft. The end result is also thought to be a normalization of the neurotransmitters within the cleft.

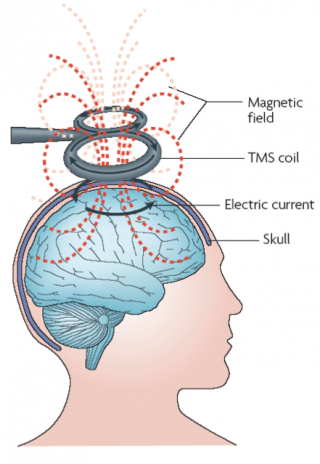

This is a relatively new, noninvasive treatment which has been proven to treat clinical depression even when prior conventional methods have failed. TMS treatments are administered in a psychiatrist's office. An electromagnet electrode is placed near the forehead and delivers magnetic pulses (approximately the strength of an MRI scan) to the brain. The session lasts for about 40 minutes. There is no sedation needed, and treatments are daily.

Numerous studies have validated the efficacy of TMS. A recent study, looking at 257 patients found that 45% maintained a full remission at 12 months, while 68% showed improvement. The FDA approved TMS in 2008 for adults.

TMS is not to be confused with ECT, or shock therapy. ECT requires anesthesia and consists of an electrical shock which triggers a seizure. TMS uses a magnetic field and is performed on an awake patient. There are vastly fewer side effects and TMS is easier to perform. Most importantly, the patient can drive themselves to and from the appointment and then go back to work right after the treatment.

TMS is the newest, most innovative procedure to combat resistant depression. It is an option for those who don't respond to one or two trials of medication or have experienced intolerable side effects. There is now a push among providers of TMS to allow it to be used as a first line treatment.

It sounds all good, but there is a downside. Treatments are very time consuming: five days a week and almost an hour a day for six weeks. And the cost for a full series will be in the neighborhood of $10,000. Insurance is gradually starting to pay, depending on the state and for some medication must be continued, both during the treatments and after.

The bottom line is that TMS is a great new addition to our armamentarium in the fight to cure depression, especially for those who have failed medication. Of course psychotherapy should still be the preferred first line treatment for new onset depression, as this is the least invasive and most cost-effective of all.