OCD

3 Kinds of OCD Thoughts and How to Deal With Them

These distinctions can help you make better use of the best available advice.

Posted February 23, 2022 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- There are three distinct kinds of OCD thoughts: intrusive thoughts, compulsive thoughts, and appraisals.

- Each kind of OCD thought requires a different coping strategy.

- Understanding the function of each of these thoughts can help someone cope more effectively with OCD.

Many people with OCD first get advice from internet chat forums or therapists untrained in OCD. Although the advice-givers are usually well-meaning, the messaging isn’t always consistent with best practices. Solutions may be offered that are technically correct, but omit key information and cause confusion.

A common suggestion, for instance, is to stop trying to control your thoughts. This is good advice, but it does not apply universally. In fact, there are times when stopping or controlling an OCD thought is the most helpful thing you can do. Here are the three main categories of OCD thoughts and how you should deal with each one.

1. The Trigger: Intrusive Thoughts

Most OCD cycles begin with an intrusive thought that causes discomfort or distress. These internal triggers can be about anything: harm, danger, immorality, or sexuality, among a range of other themes.

The essential feature of an intrusive thought is that it is unwanted and distressing. These thoughts tend to “pop up” unsolicited, and accordingly, they are outside of your control. They “intrude” like an annoying stranger who butts into your conversation.

If you try to prevent this, you’ll be frustrated again and again. Thoughts that pop in unwanted are random and meaningless. We all have them. Even good people have random dark and ugly thoughts sometimes. Attempts to suppress, neutralize, or fight with these thoughts gives them energy and attention, which makes them march louder

The best way to cope with intrusive thoughts is to accept them. Of course, this is easier said than done. Keep these three points in mind to find a path to acceptance:

- Intrusive thoughts are normal; everybody has them.

- Intrusive thoughts are meaningless; they don’t say anything about your character, your intent, or the future.

- Intrusive thoughts cannot be controlled; therefore, fighting them will cause more suffering in the long run.

Acceptance is the only way through.

2. The Response: Mental Compulsions

Because intrusive thoughts cause distress, sufferers will perform rituals to gain relief. These rituals are the response to the intrusive thoughts. They are the strategy used to reduce anxiety and find reassurance.

Most people believe that rituals are only observable behaviours, such as washing hands, checking locks, or putting things in order. However, many OCD sufferers perform mental rituals that are invisible to others. These can include attempts to neutralize the intrusive thoughts with “good” thoughts, mentally repeating lucky phrases, mentally counting to a subjectively comforting number, searching internally for self-reassuring evidence, checking to see if unwanted thoughts or feelings are present, or otherwise endlessly analyzing aspects of inner experience.

Mental compulsions are unique because they are both thoughts and behaviours. For instance, thinking a “good” thought in order to supplant a “bad” thought is not just thinking. It is a deliberate act designed to reduce anxiety and serves the same function as hand-washing. Mental rituals are actions that are performed with intent and are therefore controllable.

So while you’ll often hear that you shouldn’t try to control OCD thoughts, that advice does not apply to this category of compulsive thinking. Instead, the best way to cope with mental rituals—the response to the intrusion—is to stop them when they occur, and prevent them from recurring.

3. The Filter: OCD Appraisals

There is a third type of thinking in OCD that is important but often overlooked. These types of thoughts represent the beliefs, assumptions, and attitudes that come with OCD. Most notably, it represents the meaning that you assign to intrusive thoughts. Cognitive therapists refer to these types of thoughts as appraisals.

For example, if someone has an unwanted violent image of stabbing a loved one, what do you think it means? Do you think it makes them a bad person? Do you think it means they might actually want to do it? Or that they would be unable to stop themselves from doing it?

I wrote earlier that intrusive thoughts are distressing, but the science on OCD is more nuanced. Intrusive thoughts don’t have to be distressing. It all depends on how you appraise them. If you appraise the thought as dangerous or wrong, then anxiety will spike. But if you appraise them as random and meaningless, you’ll more likely find it acceptable to move on from them. Appraisals are therefore like a filter that determines whether your intrusive thoughts will cause anxiety.

How should you cope with appraisals? Although you may not be conscious of your appraisals much of the time, they are beliefs that you can access, evaluate, and change. They are therefore under your control. When it comes to appraisals, the solution is to find a therapist to help you identify and change the attitudes and beliefs that maintain your anxiety and motivate rituals.

Summary

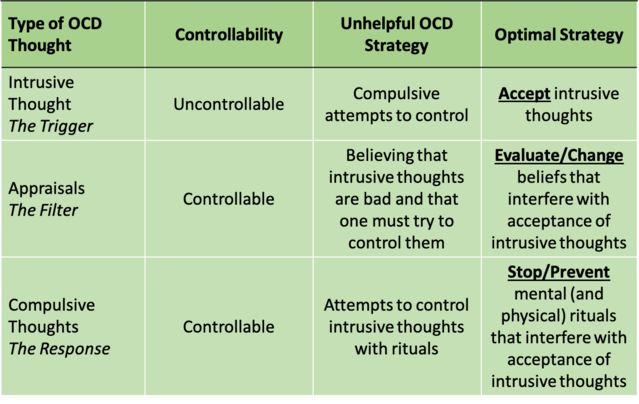

I have addressed three different forms of OCD thoughts and three different strategies for each. Although this may seem complicated, all three strategies serve the same goal: to help you accept intrusive thoughts as normal and to stop performing rituals, mental or otherwise. Reinterpreting what it means to have intrusive thoughts (i.e., changing appraisals) and stopping compulsive counter-thoughts (i.e., mental rituals) both facilitate acceptance of the unwanted thoughts you can't control. See the table below for a summary.

For more direct support in applying these distinctions and strategies, consult a qualified professional.

LinkedIn image: fizkes/Shutterstock