Education

Kids' Math and Reading Scores Drop, but Is It Sgnificant?

Are these declines really a catastrophe? Consider this perspective.

Updated June 29, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Recent standardized student math and reading scores indicated drops following the Covid19 epidemic.

- Many politicians and news media referred to these as grim.

- Overall patterns in kids' reading and math scores demonstrate remarkable stability.

- Drops in reading scores appear to be trivial, whereas math scores experienced a slight but non-trivial drop.

Recently, the National Center for Education Statistics released the Nation’s Report Card of student progress in reading and math. These scores are based on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), standardized tests given to middle school students each year since 1971. Since 2020, drops in both reading and math were noticed, likely tied to school closures during the Covid-19 epidemic. News media dutifully referred to these drops as “alarming,” an “emergency," or “grim." But how bad is the news, actually?

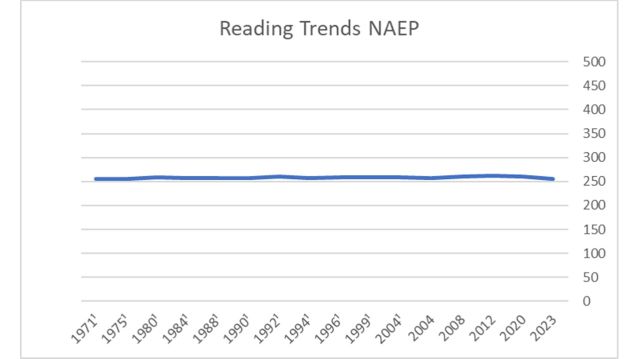

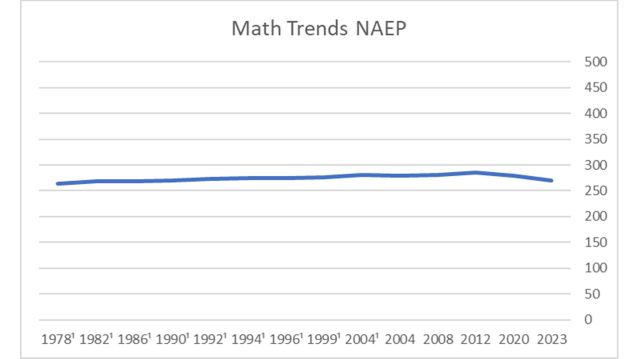

When we look at the official charts released for the NAEP, we can see a small 4-point drop in reading and a larger 9-point drop in math.

It’s worth noting two things on this chart. First, as we can see on the Y-axis, the scale scores are zoomed in. This can make small changes seem particularly dramatic. It’s not necessarily wrong to do this, but we want to observe that to take these scores in context. Second, even across 5 decades, scores overall didn’t change very much. For reading, scores improved slightly over time before becoming largely static since 2012, then dropping a bit during Covid. Math scores improved a bit more, then dropped a tiny bit since 2012, then more rapidly during Covid. Since scores can range 500 points, how worrisome is a drop of 4 or even 9 points?

Consider what we see when we look at the trends zoomed out for reading:

Or for math:

We see that, in fact, the trends are largely stable over time. To be clear, it’s not that either zooming in or zooming out are inherently incorrect, but doing so gives us a different sense of the scale of change.

Another way of thinking about it is how much change do we need to see in order to be sure that the change a) isn’t merely noise in the system, or b) isn't real but trivial—meaning it’s too small to really notice on a practical scale? We can answer this question by understanding the standard deviation of the scores. Standard deviation is a tricky stats concept, but we can think of this as something like the average amount that the typical person is likely to vary away from a mean score. To conceptualize this, think about intelligence as measured by IQ. The mean score is 100. But most people don’t get exactly a score of 100. Some people get a 101, and others get a 99. We know that a person with a 101 can learn pretty much the same things as a person with a 99. Those little changes in the score don’t mean much. So how much change do we need to see before we expect practical differences? For most people, IQ scores fall within a range of 15 (i.e., a standard deviation of 15) of 100. So, scores between 85 and 115 are all basically average. Two standard deviations away from the mean and you have people who may be intellectually disabled (an IQ of 70 or less) or may be, in the other direction, geniuses (130 and above). By comparing an observed difference in scores to the standard deviation, we can calculate a standard deviation score which I’ll call d. So, a d of 1 (basically take the amount of difference and divide it by the standard deviation) is kind of a big deal clinically. I’ve generally recommended a d of .41 as the minimum for clinically relevant, and anything less than about .20 is probably indistinguishable from noise.

So, with that in mind, we can look back at the NAEP reading and math scores. For 2023, the standard deviation for reading was 40, and for math it was 43. For reading we can take the observed drop in scores (4) divide it by the standard deviation (40) and we get a d = .10. That’s below the noise threshold, suggesting this isn’t really much of a drop. For math, the d = .21, so that’s more solid evidence for at least a small but clinically relevant drop in scores.

The conclusion is that, for math, we saw a small but meaningful drop in scores, probably attributable to Covid-19 (albeit we’re making a causal assumption from correlational data), but for reading, the drop in scores is probably too small to be meaningful.

It’s worth mentioning, too, that the drop-offs from 2012 to 2020 are too small to be clinically meaningful. Some have attributed these drops to social media use, but a) there’s little evidence to support such a connection; b) setting any date as an “inflection point” is post-hoc arbitrary, given that any year from 2004 to the present could be rationalized as an “inflection point” within a moral panic framework; and c) even if there were some causal connection, that’s a pretty weak effect for all the hubbabaloo people have raised.

In conclusion, school closures (but not social media) probably hurt kids’ learning a little bit, but catastrophizing will probably do more to garner news headlines than lead to constructive solutions.