Adolescence

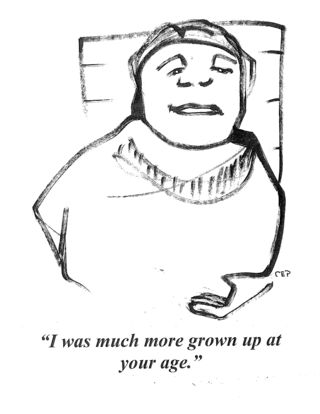

What Is the Point of Adolescence?

In times of parental frustration, the answer can be helpful to know.

Posted July 10, 2017 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Often asked by parents in frustration, the question is always a good one: “What’s the point of adolescence?” Or as one dad put it: "If I can see the endgame, it's easier for me to keep playing."

So my response follows, describing one overall point, two major developmental objectives, and four stages of growth challenges to be met.

The Overall Point

Over 10 to 12 years, usually starting in late elementary or early middle school and not winding down until a little after the college years, the overall point of adolescence is to physiologically, psychologically, and socially transform the child into a young adult.

This transformation can only begin when the girl or boy, usually around ages 9 to 13, begins to break some of the childhood attachment and similarity that securely bonded the child to parents. This break causes necessary losses that create some freedom to grow toward two developmental objectives. In this process, as the adolescent changes, the parent changes in response, and the relationship between them changes as well.

Two Major Developmental Objectives

One developmental objective is to sufficiently detach from parents and childhood so that by journey’s end the young person has acquired enough self-management freedom and responsibility to finally support a functional independence. “I can take care of myself.” A second, and equally important developmental objective, is to sufficiently differentiate from parents and childhood so that by journey’s end the young person has experimented with enough individual expression to claim a uniquely fitting identity. “I know the person I am.”

These parallel and interacting paths of growth require active effort, experience, and education. There is much work to accomplish, experimentation to try, and knowledge and skills to gain. The primary teachers for most young people are the parents who are always wrestling with a very hard decision: how much to hold on and when to start letting go.

The parent’s hard job is to stay caringly connected to the changing young person as adolescence grows them apart, which is what it is meant to do. As the young person grows older, they direct choice less and inform choice more as their daughter or son journeys through what I think of as four stages of growth, each posing growth challenges to be met.

Four Stages of Growth Challenges

Stage One: The Point Is to Separate from Childhood.

Early Adolescence (around ages 9 – 13) challenges are characterized by:

- Personal disorganization – the self-management system that was sufficient for the simpler, sheltered world of childhood is now insufficient to cope with the complexity of adolescence, hence there is more distractibility, impulsivity, forgetting, losing track of things, messiness, and other signs of personal disarray.

- A negative attitude – increased dissatisfaction from no longer being content to be defined and be treated as a child, less interested in traditional childhood activities and more boredom and restlessness from not knowing what to do, and carrying a grievance about unfair demands and limits that adults in life impose.

- Active and passive resistance – more questioning of authority, arguing with rules, delaying compliance with parental requests, letting fulfillment of normal school and home responsibilities go.

- Early experimentation – testing social rules and limits to see what can be gotten away with, including testing or ignoring traditional family rules and restraints, and often less valuing of academic effort.

Stage Two: The Point Is to Form a Family of Friends.

Mid Adolescence (around ages 13 – 15) challenges are characterized by:

- More intense conflict with parents over social freedom with peers.

- More lying to escape consequences or to do what has been forbidden.

- More self-consciousness from puberty, bodily change, and body image.

- More peer pressure to conform to belong, insecurity causing more social cruelty (teasing, exclusion, bullying, rumoring, ganging up.)

Stage Three: The Point Is to Act More Grown Up.

Late Adolescence (around ages 15 – 18) challenges are characterized by:

- More independence from doing grown-up activities – part-time employment, driving a car, dating, and recreational substance use at social gatherings.

- More significant emotional (and often sexual) involvement in romantic relationships.

- More grief over the graduation separation from old friends (and perhaps leaving family.)

- More worry about unreadiness to undertake increased worldly independence.

Stage Four: The Point Is to Step Off on One’s Own.

Trial Independence (around ages 18 – 23) challenges are characterized by:

- Lower self-esteem from not being able to adequately manage increased demands, procrastination, falling behind, breaking commitments of adult responsibility.

- Increased stress from the multiplicity of demands, fear of the future, and no clear sense of direction in life.

- High distraction from their cohort of peers who are slipping and sliding and confused about direction too, partying more to deny problems, or seeking Internet escape from responsibility, as the stage of highest substance use begins.

- Inability to catch hold as many young people can “boomerang” home after losing independent footing, to recover, and to try again.

So for me, adolescence has lots of points — from accomplishing the larger transformation, to reaching two developmental goals of growing up, to coping with challenges that can mark each stage of adolescence along the way.

The point of parenting adolescents is to foster this transformation, to support the goals of growth, and to help the young person responsibly meet and resolve the hard challenges that can arise.

Next week’s entry: After Adolescence Managing Young Adult Stress

Carl Pickhardt is the author of Surviving Your Child's Adolescence.