Friends

How to Respond to People in Crisis: Comfort In; Dump Out

Use Silk’s Ring Theory, and a spotlight, to guide your supportive intentions.

Posted September 26, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Have you ever felt awkward and unsure about what to say to someone who has fallen on hard times? You know they need support and you may feel the urge to help by offering different perspectives, silver linings, and advice. You may have similar stories to share and want to commiserate. Or, given that their journey is painful to watch, and you may confide in them how difficult it is for you to witness their suffering.

Your own pain and your desire to "fix" are common and well-intentioned, springing from your emotional empathy. But these particular attempts at support are inappropriate and even harmful because you essentially shift the spotlight away from the person who is suffering and put it on yourself. Instead of making them the focus of your concern, you steal the show by trying to be the fix-it hero, sharing your own woes, pointing out blessings in disguise, shrugging off the consequences as fate or “God’s will,” or dismissively explaining how the situation isn’t that bad because “here’s how it could be worse.” These tactics are the opposite of supportive because you cease to be the person who can hold the spotlight on them. What they need most is to be clearly visible, so that others might accompany them along this challenging, often unfixable, journey.

Clinical psychologist Susan Silk knows what it’s like to be on the receiving end of inappropriate remarks. When she was hospitalized for a life-threatening illness, a well-meaning colleague complained about how hard this ordeal was on her too, actually saying, “This isn’t just about you." This colleague was being honest. She was confiding. Perhaps she was seeking closeness. But she effectively shifted the spotlight to herself instead of keeping it on Susan, where it belonged. The result? Susan felt abandoned and adrift. The opposite of comforted.

Perhaps like Susan, in your own hour of need, you too have experienced the spotlight shifting away from you, and the accompanying feelings of abandonment.

For instance, maybe you have a suspicious lump and a scary biopsy scheduled, and your spouse reminisces about the time he was diagnosed with a tropical illness during college and how hard that was for him. Now he’s having his own pity party. Not comforting.

Or your baby dies, and your friend talks about how much this is making her fearful about her own pregnancy. And your mother expresses her deep sorrow about how she can’t see this grandchild grow up. They’ve essentially informed you that you’ve placed a great burden on them. Not supportive.

Or your home is destroyed and your relatives tell you how much they loved that house, and how angry they are that it couldn’t be saved or how sad they are about not being able to visit you there anymore. And now you feel like you have to comfort them. Not helpful.

After Susan Silk’s disheartening experience, she was inspired to create Ring Theory, a model of caring that clearly, concretely delineates appropriate versus inappropriate interactions with everyone around you during times of crisis or tragedy. Whether hard times have fallen on you or someone else, the basic idea is “comfort in; dump out.”

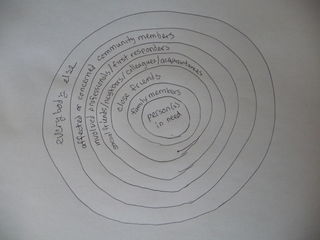

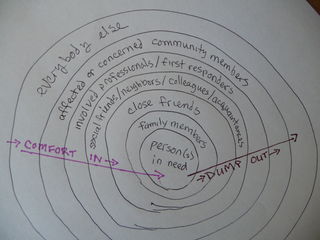

Here’s how it works: Imagine concentric circles. In the center ring is the person or people who are the most directly affected, aggrieved, and afflicted. In the next ring are close relatives; the next ring holds true friends; the ring after that holds acquaintances like neighbors, colleagues, distant relatives, and casual friends. The next circle holds caregivers who are professionally involved as sources of support or assistance, including doctors, nurses, therapists, and first responders, but the tragedy doesn’t touch their personal lives. The outermost circles contain community members and bystanders. They may be interested in this family or the situation, but they don’t have a direct personal or professional connection. This outermost ring can also include professionals like staff supervisors, hospital administrators, support staff, or any caregivers or responders who were not directly involved in caring for the family, plus journalists reporting the news and onlookers from the general public.

The basic rule is Comfort IN; Dump OUT.

Now, imagine a spotlight. Train it on the center ring, so it is most brightly lit, making it abundantly clear where the focus of caregiving should be. Now notice how the light is diffused across all the rings, which become more dimly lit as they span ever outward. To the people in rings brighter than yours, it is appropriate to sympathize, but not complain. If you want to complain or seek your own comfort, turn to the people in your ring or better yet, the people in rings that are more dimly lit. That’s because they are naturally less directly afflicted by this crisis. The spotlight also demonstrates a key component of offering comfort: Never steal the spotlight!

If you’re in the center ring, it sucks, but you're smack in the spotlight and you can say anything to anybody. You can talk about your experience, express your feelings, complain, cry, despair, bitch, and moan.

If you’re in any outer ring, you too can talk about your experience and emotions, complain, cry, despair, bitch, and moan, but NOT with anyone who is in a ring closer to the center than yours. That would shift the spotlight and brighten your outer ring at the expense of dimming their inner ring. Even if you’re a close friend of someone in an inner ring, it is inappropriate to confide in them about your woes or how difficult this is for you to watch. That would be shifting the spotlight from their rings to yours.

Instead, dump out to the folks who inhabit a more dimly lit circle.

Likewise, if you’re a medical professional or first responder, it’s inappropriate to share your own experiences with the family you're assisting, or their friends or acquaintances, but you can confide in colleagues or supervisors, or express your dismay and struggles to your own support network of family and friends, of course keeping confidential details to yourself.

Now, does this mean that you can't show any emotion in the presence of people experiencing hard times? Quite the contrary; it is appropriate to reflect their emotions in a show of compassion. For instance, if distraught bereaved parents are crying and you're moved to shed a tear, they can find this communal grieving quite comforting. But it's only appropriate if you're gently sharing their moment. If you're crying with greater intensity than they are, then it becomes your moment, and it's time to excuse yourself because you're in the process of shifting the spotlight onto yourself.

Recap: Concentric Circles. Spotlight Centered. Comfort In. Dump Out.

What’s interesting about these concepts is that they can be applied to any crisis — weather, medical, legal, social, emotional, environmental, financial, existential. Indeed, here’s another example of dumping in and shifting the spotlight to demoralizing effect: Your community is devastated by a hurricane or violence from outsiders. A prominent leader, instead of showing support with compassion and pledging assistance, dumps in, making light of the devastation or blaming the victims. Utterly inappropriate.

Naturally, dumping — in or out — is easier to do than comforting. Dumping can be unedited, unconsidered, and reactive — hence, best directed toward those less affected by the crisis. In sharp contrast, comfort requires far more care and sensitivity in order to truly support those more directly affected. My next post will look at how to effectively and appropriately send “Comfort In."